In the realm of high-voltage power systems, the demand for reliability and compactness has propelled the widespread adoption of SF6 gas-insulated metal-enclosed switchgear (GIS). Among its core components, the disconnector plays a pivotal role in circuit isolation. The disconnector’s enclosure, typically a shell casting, must withstand internal SF6 gas pressures ranging from 0.40 to 0.76 MPa during operation and must not fail under pressures up to five times the design value. Ensuring the structural integrity of these shell castings is therefore paramount for safe and economical operation. This study focuses on a comprehensive strength assessment of a cast aluminum-silicon-magnesium alloy disconnector shell used in GIS, employing finite element analysis (FEA) and experimental validation. The objective is to verify that the shell castings meet stringent design requirements and to elucidate stress distribution characteristics, particularly at geometric discontinuities, to inform future design optimizations.

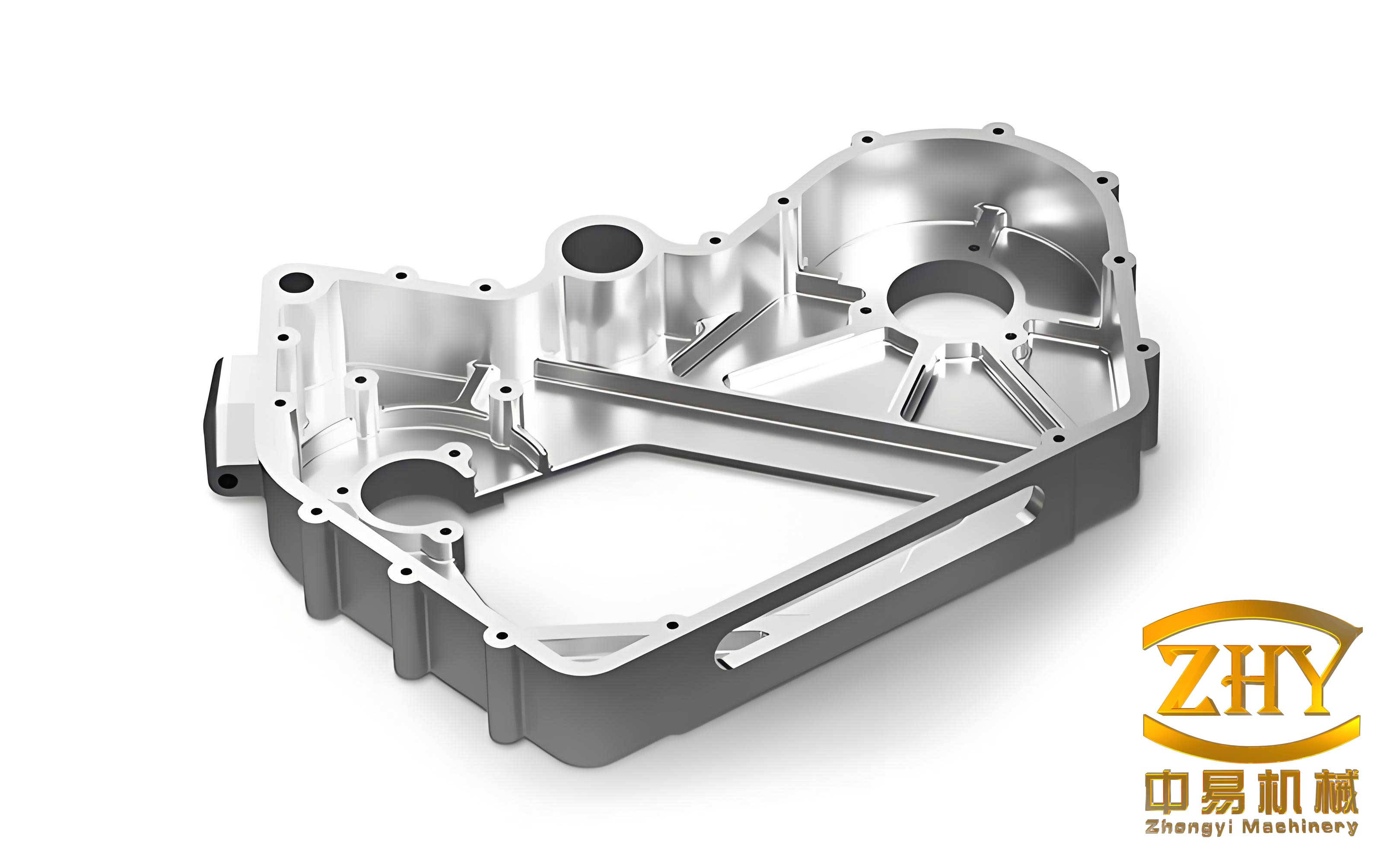

Shell castings, by their nature, involve complex geometries often featuring openings, flanges, and intersecting cylindrical sections. These features introduce stress concentrations and discontinuities that can compromise strength if not properly accounted for. Traditional analytical methods fall short for such intricate shapes, making numerical techniques like finite element analysis indispensable. In this work, I developed a detailed 3D model of the entire disconnector assembly and performed a structural stress analysis using ANSYS software. The process involved applying design pressures, boundary conditions, and preloads from fasteners to simulate real-world operating conditions. The core of the assessment lies in the stress categorization and linearization procedures prescribed for pressure vessel design, allowing for a rigorous strength evaluation against established criteria.

The fundamental principle governing the design of pressure-containing components like these shell castings is the classification of stresses based on their nature and effect. Stresses are generally categorized into primary, secondary, and peak stresses. Primary stresses, such as membrane and bending stresses, are caused by imposed mechanical loads and can lead to catastrophic failure if excessive. Secondary stresses, like thermal or localized bending stresses, are self-limiting and arise from constraints; they do not cause collapse but may influence fatigue life. Peak stresses are highly localized and are primarily considered in fatigue analysis. For static strength assessment under design loads, peak stresses are typically disregarded. The allowable limits for these stress categories, as per standard design codes, are summarized in Table 1.

| Stress Category | Allowable Limit |

|---|---|

| Primary Membrane Stress (Pm) | Sm |

| Primary Bending Stress (Pb) | — |

| Primary Membrane + Primary Bending (Pm + Pb) | 1.5 Sm |

| Primary Stress + Secondary Stress (PL + Pb + Q) | 3 Sm |

Here, Sm represents the material’s allowable stress, derived from its yield strength with an appropriate safety factor. For the cast aluminum alloy ZL101A-T6 used in these shell castings, the yield strength is 275 MPa. Applying a safety factor, the design allowable stress Sm is taken as 55 MPa. The strength assessment involves extracting these categorized stress values from the FEA results. However, finite element output provides combined stress values (e.g., von Mises stress) without distinction. To decompose them, the method of constructing a primary structure is employed. This involves analyzing the model under loads that produce only primary stresses (e.g., by applying pressure while allowing free displacement at constraints to prevent secondary bending), and then comparing with the full analysis to isolate the secondary components.

A critical step in this process is stress linearization. Along a chosen path through the shell wall thickness at a critical location, the varying stress is resolved into equivalent membrane and bending components. The path selection follows specific rules: it must start at the point of maximum stress, traverse the entire wall thickness, and be perpendicular to the shell’s midsurface at the section. This linearization allows for the direct application of the limits in Table 1. The mathematical representation for calculating stresses from strain measurements, used later in experimental validation, is given by the generalized Hooke’s law for plane stress conditions. For a biaxial strain state measured with strain gauges, the stresses in the x and y directions are:

$$ \sigma_x = \frac{E}{1 – \mu^2} (\varepsilon_x + \mu \varepsilon_y) $$

$$ \sigma_y = \frac{E}{1 – \mu^2} (\varepsilon_y + \mu \varepsilon_x) $$

where \( E \) is the Young’s modulus (70 GPa for ZL101A-T6), \( \mu \) is Poisson’s ratio (0.33), and \( \varepsilon_x, \varepsilon_y \) are the measured strains in the orthogonal directions.

The design of the shell castings begins with determining the wall thickness. For cylindrical sections under internal pressure, the minimum required thickness \( \delta \) can be estimated using the formula derived from thin-wall theory, modified for practical considerations:

$$ \delta = \frac{K \cdot P_b \cdot D}{2 \cdot [\sigma] – P_b} + C $$

where:

\( P_b \) = Design pressure (MPa),

\( D \) = Inner diameter of the cylinder (mm),

\( [\sigma] \) = Allowable stress of the material (MPa),

\( K \) = A coefficient accounting for stress concentration factors at openings, heat treatment variations, and other uncertainties,

\( C \) = A corrosion/erosion allowance or additional thickness for manufacturing tolerances (mm).

For the disconnector shell casting in this study, considering a design pressure of 0.64 MPa (accounting for a temperature rise to 80°C from a nominal 0.5 MPa rating), inner diameters of main and branch cylinders, and applying appropriate factors, the wall thicknesses were determined as 12 mm for the main cylindrical body and 20 mm for the branch sections. These dimensions formed the basis for the 3D geometric model. The complete assembly model includes the main shell casting, flanges, cover plates, and bolts. The material properties for all components are detailed in Table 2 and Table 3.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | 2.77 |

| Young’s Modulus, E (GPa) | 70 |

| Yield Strength (MPa) | 275 |

| Allowable Stress, Sm (MPa) | 55 |

| Poisson’s Ratio, μ | 0.33 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | 7.85 |

| Young’s Modulus, E (GPa) | 200 |

| Yield Strength (MPa) | 460 |

| Poisson’s Ratio, μ | 0.3 |

The finite element model was built with high-fidelity geometry. Tetrahedral and hexahedral elements were used for meshing, with mesh refinement applied at anticipated high-stress regions like fillets and openings. Boundary conditions simulated the actual mounting: one end face of the shell casting was fixed (encastre), while the internal surface was subjected to a uniform pressure of 0.64 MPa. Pre-tension loads were applied to the bolts connecting the flanges and cover plates to simulate the clamping force. The solved FEA model revealed the von Mises stress distribution across the shell castings. As expected, the highest stresses were localized at geometric discontinuities. The maximum stress occurred around bolt holes on the flanges; however, this is primarily a compressive stress due to bolt preload, and the material’s compressive strength is significantly higher than its tensile yield strength. Therefore, for the shell casting’s pressure-containing function, the critical areas are the intersections (junctures) between the main cylinder and branch cylinders, and the regions surrounding larger openings.

Two specific locations, labeled Zone ① and Zone ②, were identified as having the most significant stress concentration from pressure loading. Zone ① is at the intersection of the main cylinder and a large branch, while Zone ② is at the junction between two branches. Stress linearization paths were defined through the wall at these locations according to the rules mentioned earlier. The linearization process decomposed the total stress into membrane and bending components. Using the primary structure method to separate primary and secondary stresses, the final categorized stress values for assessment were obtained, as shown in Table 4.

| Stress Type / Assessment | Zone ① Path Stress (MPa) | Zone ② Path Stress (MPa) | Allowable Limit (MPa) | Check |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Membrane Stress (Pm) | 24.566 | 39.597 | Sm = 55 | Pass |

| Primary Bending Stress (Pb) | 6.7 | 5.3 | — | — |

| Pm + Pb | 75.934 | 75.953 | 1.5Sm = 82.5 | Pass |

| Primary + Secondary (PL+Pb+Q) | 82.634 | 81.253 | 3Sm = 165 | Pass |

The assessment confirms that all stress categories are well within their allowable limits. The shell castings, therefore, possess adequate strength for the design pressure. Further analysis of the FEA results provides valuable insights for designing such shell castings. The size and spatial arrangement of openings significantly influence stress distribution. Smaller openings tend to cause highly localized stress concentration that decays rapidly, leaving only membrane stress away from the hole. In contrast, larger openings induce bending stresses that extend further into the surrounding material of the shell castings. Moreover, the intersections (or crotch zones) between cylinders are natural stress raisers. The finite element analysis clearly shows that the stress magnitude at these junctions is sensitive to the fillet radius. A small radius creates a sharp notch effect, leading to higher peak stresses. Therefore, a key design recommendation for shell castings is to maximize the transition fillet radius at all intersections to smooth the load path and reduce stress concentration factors.

To validate the numerical findings, a hydrostatic pressure test was conducted on a physical prototype of the disconnector shell casting. Strain gauges were mounted at multiple strategic locations on the external surface of the shell castings, corresponding to high-stress zones identified by FEA, including points equivalent to Zone ① and Zone ②. The shell was filled with water and pressurized incrementally up to the design pressure of 0.64 MPa. At each pressure step, strain readings from all gauges were recorded. Using Equations (1) and (2), the biaxial stresses at each point were calculated. The pressure-strain and pressure-stress curves for the points corresponding to Zones ① and ② were plotted. The data showed a linear elastic response throughout the loading range, confirming no yielding occurred. The experimentally measured stresses at the design pressure aligned closely with the FEA predictions for those locations. Crucially, the combined stress \( \sigma_{xy} \) (calculated as an equivalent stress from the two components) at these critical points was found to be below the 1.5Sm limit, providing experimental corroboration that the shell castings satisfy the strength requirement.

The close agreement between the finite element analysis and the hydrostatic test results serves two important purposes. First, it validates the accuracy of the modeling methodology, including material properties, boundary conditions, and mesh quality. This gives confidence in using FEA as a predictive tool for optimizing future designs of similar shell castings. Second, it empirically verifies the structural adequacy of the current shell casting design under static pressure loads. The successful test confirms that the manufacturing process, which includes casting, heat treatment (T6 condition), and machining, produces shell castings with consistent mechanical properties that meet the design intent.

In conclusion, this integrated study involving detailed finite element simulation and experimental pressure-strain testing thoroughly evaluates the strength of cast aluminum disconnector shell castings for GIS applications. The key findings are: Firstly, the stress distribution in complex shell castings is highly influenced by geometric discontinuities, with intersections and large openings being critical areas. Secondly, through rigorous stress categorization and linearization following pressure vessel standards, the analyzed shell castings demonstrate ample strength margins, with all evaluated stresses falling within allowable limits. Thirdly, the hydrostatic test data strongly corroborate the numerical models, affirming their reliability. For designers, the main practical implication is the necessity to carefully manage opening sizes and locations and to employ generous fillet radii at all junctions in shell castings to mitigate stress concentrations. This investigation establishes a robust framework for the analysis and validation of shell castings in high-voltage equipment, contributing to safer and more reliable GIS products. Future work could extend this approach to dynamic loads, seismic analysis, or fatigue assessment to cover a broader spectrum of operational conditions for these critical shell castings.