In my extensive experience with vacuum-assisted high-pressure die casting, the precise control of process parameters is not merely a recommendation—it is the absolute cornerstone for achieving sound, high-integrity castings. Among these parameters, the determination of the vacuum cut-off point, the moment when the evacuation of the die cavity is terminated, stands out as one of the most critical and often misunderstood factors. Its correct setting directly dictates the effectiveness of the entire vacuum process in combating the pervasive defect of porosity in castings. An incorrectly timed cut-off, whether too early or too late, can render the sophisticated vacuum system ineffective or even counterproductive, leading to flawed components, production downtime, and increased costs. This article delves into the mechanics of vacuum die casting from a practitioner’s perspective, providing a detailed analysis of how the vacuum cut-off point influences cavity evacuation and, ultimately, the formation and reduction of gas-related porosity in castings.

The Fundamental Challenge: Gas Entrapment and Porosity

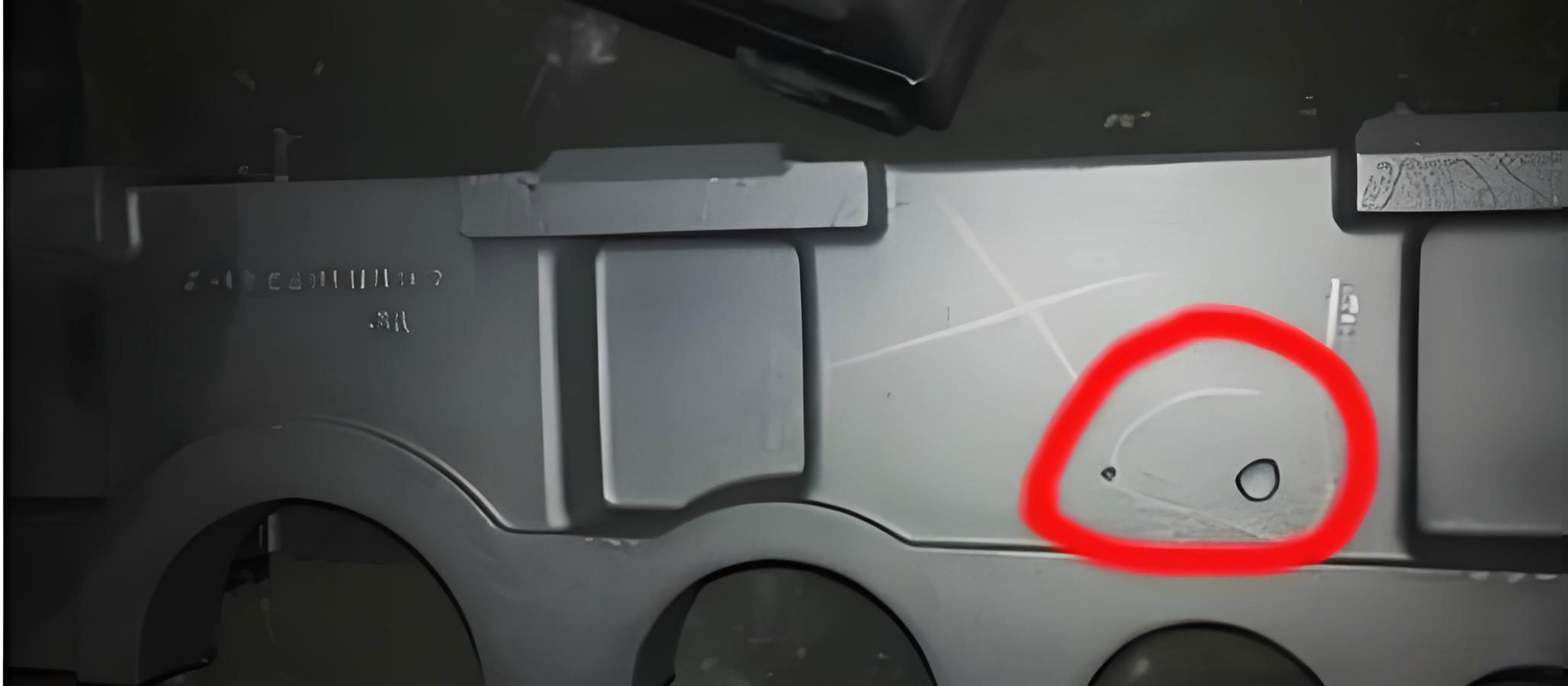

The primary adversary in conventional high-pressure die casting is entrapped air. As the molten metal is injected at extremely high speeds into the die cavity, the air present inside has minimal time to escape through narrow vents and parting lines. This trapped air is compressed by the advancing metal front, becoming dissolved in the molten alloy or forming high-pressure pockets. Upon solidification, these pockets are revealed as subsurface or surface pores, drastically weakening the mechanical properties, impairing pressure tightness, and making subsequent heat treatment or welding hazardous due to blistering. The quest to minimize this porosity in castings is a constant driver for process innovation.

Vacuum Die Casting: A System Overview

Vacuum die casting addresses this by actively evacuating the air from the cavity and shot sleeve before and during the injection phase. A typical system comprises several key components: a vacuum tank (reservoir), high-speed vacuum valves, a control unit, and position sensors on the injection plunger. The process sequence is meticulously synchronized:

- Die closing and slow shot phase initiation.

- Activation of the vacuum valve(s), connecting the cavity to the vacuum tank.

- Evacuation of the cavity and shot sleeve.

- Vacuum cut-off: Closure of the vacuum valve, isolating the cavity from the tank.

- Transition to the high-speed injection phase.

- Intensification (pressure build-up) and dwell time.

The pivotal moment occurs between steps 3 and 4. The valve must close at the optimal instant—after sufficient air has been removed to create a significant negative pressure (typically -0.06 to -0.09 MPa gauge), but before the molten metal front reaches the gate and risks being drawn into the vacuum system.

Defining and Quantifying the Vacuum Cut-off Point

In practice, the vacuum cut-off point is defined by the position of the injection plunger. It is set as a distance, measured in millimeters, before the plunger reaches the “fast shot switch” position—the trigger point for high-speed injection, which is generally when the molten metal reaches the gate. Let’s denote:

- $d_{cut}$ = Vacuum cut-off distance (mm) before the fast shot switch.

- $P_{cav}(t)$ = Pressure in the die cavity as a function of time.

- $V_{cav}$ = Volume of the die cavity and shot sleeve ahead of the plunger.

- $Q_{vac}$ = Volumetric flow rate of the vacuum system.

The goal is to maximize the negative pressure achieved at the moment the metal enters the cavity. A simplified model for the pressure decay can be derived from the ideal gas law and flow through an orifice (the vacuum valve and lines):

$$P_{cav}(t) = P_{initial} \cdot e^{-\left(\frac{Q_{vac}}{V_{cav}}\right)t}$$

However, $t$ is directly related to $d_{cut}$. The available evacuation time $t_{evac}$ is the period from valve opening until the plunger reaches the position $d_{cut}$ before the fast shot point. If the slow shot velocity is $v_{slow}$, then:

$$t_{evac} \approx \frac{L_{sleeve} – d_{cut}}{v_{slow}}$$

where $L_{sleeve}$ is the length of the shot sleeve from the pour hole to the fast shot point.

Substituting, we see the achieved cavity pressure is exponentially related to the cut-off distance:

$$P_{cav}(d_{cut}) \propto e^{-\left(\frac{Q_{vac}}{V_{cav}}\right) \cdot \frac{(L_{sleeve} – d_{cut})}{v_{slow}}}$$

This illustrates the trade-off: a smaller $d_{cut}$ (cut-off later) allows more evacuation time, leading to a lower $P_{cav}$ (higher vacuum), which should directly reduce porosity in castings. But this benefit has a strict physical limit.

The Consequences of Incorrect Cut-off Point Setting

The practical window for $d_{cut}$ is narrow, bounded by two failure modes:

| Cut-off Setting | Mechanical Consequence | Effect on Porosity in Castings | Production Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too Early ($d_{cut}$ too large) | Insufficient evacuation time. Air re-ingresses into the cavity through parting lines/clearances after valve closure. | Minimal reduction in air content. Final casting density and porosity levels接近 conventional casting. Vacuum system investment yields little return. | Inefficient use of cycle time. |

| Too Late ($d_{cut}$ too small,接近 0) | Molten metal is drawn into vacuum valves and lines during evacuation. Gates may be partially blocked by prematurely advanced metal. | Unpredictable filling, turbulence, and potential for new gas entrapment. Severe contamination of vacuum system. | Catastrophic. Requires lengthy downtime for cleaning valves and tank. Damages expensive equipment. |

| Optimal ($d_{cut}$ ~ 15-20 mm) | Maximum safe evacuation time achieved. Cavity under significant negative pressure as metal enters. | Maximum reduction in entrapped air. Density increase ≥1%. Porosity is minimized, often changing from macro- to micro-scale. | Stable, robust process. High yield and equipment longevity. |

The risk of metal draw-in is the dominant constraint. As the plunger advances during the slow shot, the metal meniscus rises in the shot sleeve. If the vacuum valve is still open when this meniscus passes the gate, the pressure differential will actively pull metal into the cavity prematurely and potentially up into the vacuum line. This is why the valve must be closed just before the metal reaches the gate—allowing the last moment of evacuation but preventing any fluid connection.

Experimental Validation: Data-Driven Optimization

To move from theory to practice, I conducted a structured Design of Experiment (DoE) on a production part—a lever housing. The primary variable was the vacuum cut-off distance $d_{cut}$. The goal was to quantify its effect on part quality, specifically mass (as a proxy for density and porosity in castings) and mechanical strength. The stable process parameters were as follows:

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Locking Force | 5000 | kN |

| Slow Shot Velocity ($v_{slow}$) | 0.25 – 0.30 | m/s |

| Fast Shot Velocity | 2.0 – 2.2 | m/s |

| Intensification Pressure | 24 | MPa |

| Metal Temperature (Al-Si alloy) | 640 ± 10 | °C |

| Vacuum Tank Pressure | ≤ -0.06 | MPa (gauge) |

The cut-off distance was varied systematically from 5 mm to 35 mm before the fast shot switch. For each setting, 10 consecutively produced parts were weighed (to an accuracy of ±0.1g) and their tensile bars were tested. The results are summarized below:

| Cut-off Distance $d_{cut}$ (mm) | Average Part Mass (g) | Mass Increase Relative to 5mm (%) | Estimated Density Increase (%) | Average Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Strength Increase Relative to 5mm (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 385.8 | 0.00 (Baseline) | 0.00 | 245 | 0.0 |

| 10 | 388.1 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 251 | 2.4 |

| 15 | 389.7 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 256 | 4.5 |

| 20 | 390.2 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 257 | 4.9 |

| 25 | 389.9 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 255 | 4.1 |

| 30 | 388.5 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 250 | 2.0 |

| 35 | 387.0 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 247 | 0.8 |

The data paints a clear picture. As $d_{cut}$ is reduced from 35 mm to 15-20 mm, both part mass and tensile strength show a significant peak. The mass increase of over 1% is not trivial; it represents the absence of a substantial volume of gas. Using the density of the alloy ($\rho \approx 2.7$ g/cm³), the mass difference of 4.4g between the 5mm and 20mm settings corresponds to a displaced gas volume $V_{gas}$ of:

$$V_{gas} = \frac{\Delta m}{\rho} = \frac{4.4}{2.7} \approx 1.63 \text{ cm}^3$$

This is equivalent to eliminating a spherical pore with a diameter of:

$$d_{pore} = \sqrt[3]{\frac{6 V_{gas}}{\pi}} = \sqrt[3]{\frac{6 \times 1.63}{\pi}} \approx 1.45 \text{ cm}$$

Eliminating a gas pocket of this size from the casting’s microstructure has a transformative effect on its integrity. The plateau and subsequent decline in properties for $d_{cut}$ settings below 15 mm (25, 30, 35 mm) confirm the “too early” failure mode—insufficient vacuum is pulled, and air re-ingression negates the benefit. The optimal window is firmly established between 15 and 20 mm for this specific machine, shot sleeve design, and vacuum system capacity.

Advanced Considerations and System Integration

Optimizing the vacuum cut-off point does not occur in isolation. It is part of a holistic process optimization. Several interacting factors must be considered:

- Slow Shot Profile: A consistent, well-tuned slow shot phase is essential. Any surging or hesitation in the plunger motion changes the timing relationship, making a fixed $d_{cut}$ position unreliable. A closed-loop controlled slow shot is highly recommended.

- Vacuum System Capacity: The $Q_{vac}$ term in our earlier equation is crucial. A larger pump and tank system with high-flow valves can achieve the target vacuum level faster, potentially allowing for a slightly larger $d_{cut}$ as a safety margin without sacrificing performance.

- Die Sealing:

The effectiveness of the entire process hinges on the die’s ability to maintain the vacuum after the valve closes. Worn parting lines, inadequate clamping force, or poor sealing around ejector pins and slides will cause rapid pressure equalization, making any vacuum cut-off point optimization futile. The leak rate $Q_{leak}$ must be negligible compared to $Q_{vac}$.

$$P_{cav, final} \propto e^{-\left(\frac{Q_{vac} – Q_{leak}}{V_{cav}}\right) t_{evac}}$$

If $Q_{leak}$ is significant, the exponent approaches zero, and no vacuum is sustained. - Real-time Monitoring: The most advanced approach involves using a cavity pressure sensor. Instead of relying solely on a plunger position, the vacuum valve can be commanded to close based on the actual measured cavity pressure reaching a predefined threshold (e.g., -0.08 MPa). This adaptive control compensates for variations in shot sleeve fill, lubrication, and minor seal wear.

Conclusion and Practical Guidelines

Based on both theoretical analysis and empirical data, the following conclusions and guidelines can be firmly stated for minimizing porosity in castings through vacuum die casting:

- The vacuum cut-off point is a decisive process parameter. Its optimization is non-negotiable for realizing the full benefits of the vacuum investment.

- The optimal setting strikes a balance between maximizing evacuation time and preventing molten metal ingress into the vacuum system. For most cold chamber machines with standard shot sleeve designs, this point lies within the range of 15 to 20 millimeters before the plunger triggers the high-speed injection phase.

- When correctly implemented, vacuum die casting with an optimized cut-off point can reliably increase the density of aluminum die castings by 1% or more. This translates directly to a proportional reduction in the volume fraction of gas porosity in castings, significantly enhancing tensile strength, elongation, and pressure tightness.

- This optimization must be part of a systems approach, requiring a stable slow shot, a well-sealed die, and adequate vacuum pump capacity. The process is robust only when all these elements are in control.

In summary, mastering the timing of the vacuum cut-off is not just a technical detail; it is the key that unlocks the potential of vacuum-assisted die casting to produce components with dramatically reduced internal defects, pushing the capabilities of die cast parts into more demanding structural and safety-critical applications. The fight against porosity in castings is won or lost in these final milliseconds before the metal storm fills the cavity.