The development of an automobile turbocharger housing, a quintessential example of a complex, thin-walled, and high-integrity shell casting, represents a significant challenge in foundry engineering. Its successful production is a true test of a foundry’s capabilities in process design, metallurgy, and quality control. In my experience, the advent of sophisticated numerical simulation software has fundamentally transformed this development process. It acts as a digital crucible, allowing for the virtual testing and optimization of gating and feeding systems before any metal is poured, thereby dramatically reducing lead times, physical trial costs, and technical risk. This article details my first-person journey in developing a compact turbocharger shell casting using MAGMA software, highlighting the iterative dialogue between simulation predictions and practical foundry results that led to a sound, production-ready process.

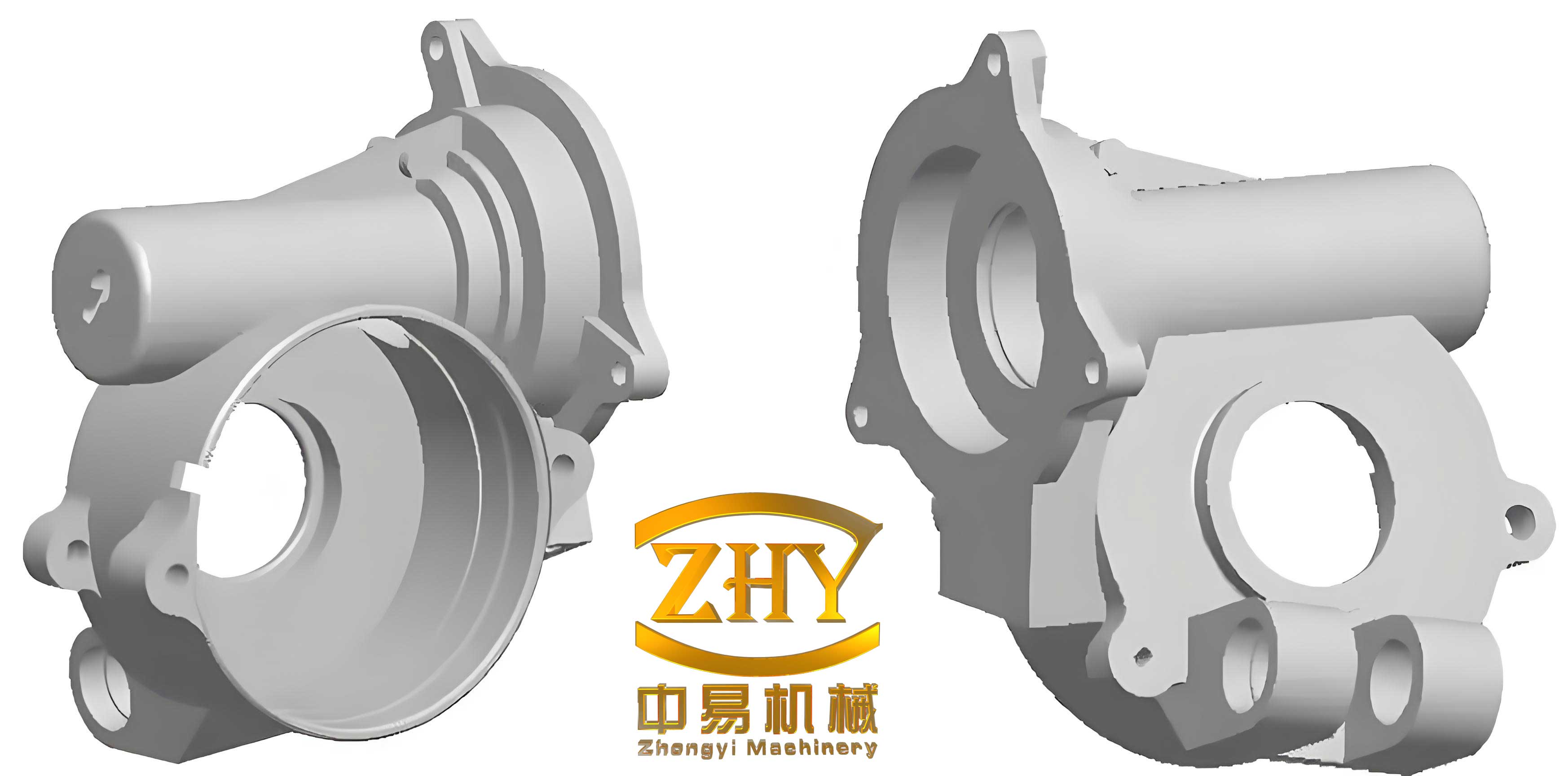

The challenge began with the component itself. The casting, with a mass of approximately 4 kg and overall dimensions of 170 mm x 160 mm x 100 mm, featured a complex internal volute (turbine scroll) separated from external mounting bosses by thin walls. The minimum wall thickness was a mere 4 mm, demanding excellent mold-filling characteristics. The material specification was compacted graphite iron (CGI, or vermicular graphite iron), chosen for its superior combination of thermal conductivity, fatigue strength, and damping capacity compared to flake graphite iron, and better thermal conductivity than ductile iron—all critical for a component exposed to high exhaust gas temperatures and thermal cycling. The most stringent technical requirement pertained to porosity on critical functional surfaces: only a very limited number of micro-shrinkage pores were permissible, with strict limits on their size and distribution.

Our production method was automated shell molding, a process excellent for producing high-dimensional accuracy and good surface finish shell castings in high volume. The mold layout was horizontal parting with two cavities per pattern to optimize productivity. The initial process design was based on established principles for pressurized gating systems and directional solidification.

| Component | Total Cross-Sectional Area (mm²) | Ratio (Σ) |

|---|---|---|

| Sprue (Downsprue) | 1200 | 2.0 |

| Runner | 900 | 1.5 |

| Ingates | 600 | 1.0 |

The gating ratio, ΣFsprue : ΣFrunner : ΣFingate = 2.0 : 1.5 : 1.0, defined a choked system at the ingates to promote rapid and non-turbulent filling. To achieve directional solidification and feed the isolated thermal masses, a combination of risers was employed. A larger hot side riser (65 mm diameter, 100 mm height) was placed adjacent to a thick section of the volute, connected by a substantial neck (23 mm x 33 mm). A smaller top riser (50 mm diameter, 70 mm height) was positioned on a side boss, serving both as a feeder and a vent, with a neck of 10 mm x 25 mm.

| Riser Type | Diameter (mm) | Height (mm) | Neck Dimensions (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Side Riser | 65 | 100 | 23 x 33 |

| Top Riser | 50 | 70 | 10 x 25 |

Prior to any physical prototyping, this entire system was built in 3D CAD and imported into the MAGMAsoft simulation environment. The virtual casting process began with meshing, where the geometry was discretized into over 5 million finite difference cells—a resolution fine enough to capture the thin walls and critical features of this shell casting. Material properties were assigned from the software’s extensive database: GJV-450 for the iron, with defined solidus and liquidus temperatures and latent heat, Green-Sand for the shell mold, and Furan for the core assembly. Key interfacial heat transfer coefficients (HTCs) were defined, such as the HTC between the casting and the mold (TempIron database) and a constant value for chill interactions.

The simulation of the filling process was the first critical validation. The results showed a smooth, sequential fill without evidence of turbulent splashing or air entrapment. The temperature field during filling confirmed that the risers remained the hottest regions, a prerequisite for their function as feeders. The subsequent solidification simulation told a more nuanced story. The macro-view showed a promising pattern: the thin walls of the volute solidified first, and the risers themselves were the last to freeze, seemingly confirming the principle of directional solidification. The Niyama criterion, a local predictive indicator for shrinkage porosity based on thermal gradient (G) and cooling rate (R), was calculated throughout the casting. While large areas showed low risk, a region of concern was highlighted.

Despite the apparently sound macro-solidification, the simulation predicted a high probability of micro-shrinkage in a specific area: the junction zone of the hot side riser neck. The reason became clear upon analyzing the thermal fields at advanced stages of solidification (e.g., 80-90% solidified). A small, isolated liquid pool was forming in the casting body just beyond the riser neck. Although the riser was still liquid, its feeding path to this isolated pool was becoming blocked by a growing solid network within the narrow connecting sections, effectively creating a “hot spot” that could not be fed. The thermal geometry created an extended and ineffective feeding distance for that particular region of the shell casting.

Guided by this virtual insight, we produced the first prototype castings. Dimensional and visual inspection was positive, but radiographic and, more definitively, sectioning analysis confirmed the simulation’s prediction. The area near the hot side riser neck exhibited micro-porosity exceeding the strict allowable limits, with a measured porosity level that rendered the component non-conforming. The digital crucible had correctly identified a flaw invisible in the initial 2D sectional drawings.

The challenge was to enhance solidification control in that specific internal hot spot without redesigning the entire gating or risering system. The solution was the strategic placement of a chill. The goal of a chill is to locally increase the cooling rate, shifting the solidification front and modifying the temperature gradient. In this case, a contoured chill was designed to fit against the internal circular plane of the turbine chamber wall, precisely in the area that was remaining liquid too long. Its dimensions were 50 mm (length) x 15 mm (width) x 15 mm (thickness).

| Component | Dimensions (mm) | Location | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contoured Chill | 50 x 15 x 15 | Internal turbine chamber wall | Eliminate isolated liquid pool, enhance directional solidification towards riser. |

The modified process was simulated again. The results were strikingly different. The solidification sequence was now altered; the chilling effect accelerated the cooling of the problematic internal wall. This eliminated the formation of the isolated liquid pool and effectively shortened the feeding distance for the side riser. The thermal gradient was improved, and the Niyama criterion values in the riser neck region moved solidly into the “sound” category. The modified thermal dynamics can be conceptually summarized by looking at how the chill affects the local solidification time and thermal gradient. The primary function is to steepen the thermal gradient (G) at the critical location. A simplified representation of the heat extraction effect can be related to Fourier’s law and the concept of solidification time (Chvorinov’s Rule).

The heat flux ($q$) extracted by the chill is governed by:

$$q = h_{chill} \cdot (T_{melt} – T_{chill})$$

where $h_{chill}$ is the effective heat transfer coefficient at the chill-casting interface, $T_{melt}$ is the metal temperature, and $T_{chill}$ is the initial chill temperature. This high heat flux drastically reduces the local solidification time ($t_f$), which according to Chvorinov’s Rule is proportional to the square of the volume-to-surface area ratio ($V/A$):

$$t_f = B \cdot \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n$$

where $B$ is the mold constant and $n$ is an exponent (typically ~2). The chill effectively reduces the effective $(V/A)$ ratio for that region, making it solidify earlier and preventing it from becoming an isolated hot spot. This ensures the feeding path from the riser remains open until the final stages of solidification.

Physically implementing this change was straightforward in the shell molding process. The contoured chill was placed on the core before mold assembly. The subsequent production runs yielded castings that, upon sectioning, showed a complete elimination of the micro-shrinkage defect in the critical area. The correlation between the final simulation prediction and the physical casting quality was exact. This successful iteration validated not only the specific solution but the overall methodology of using simulation as the primary development tool for complex shell castings.

Reflecting on this project, several key insights emerge regarding the development of high-integrity shell castings:

- Simulation as a Proactive Design Tool: Numerical simulation moves the foundry engineer from a reactive, trial-and-error paradigm to a proactive, predictive one. It identifies potential defects—like the isolated liquid pool—that are not obvious from traditional modulus calculations or 2D section reviews.

- The Criticality of Local Thermal Management:

For complex geometries like a turbocharger housing, global directional solidification to a riser is often insufficient. Localized thermal modifiers, such as chills or cooling fins in the mold, are frequently essential to control solidification in isolated hot spots and ensure soundness. The strategic use of a small chill proved far more efficient than enlarging risers or redesigning the entire gating.

- Quantitative Process Calibration: The simulation’s accuracy depends on correct input parameters, particularly material properties and interfacial heat transfer coefficients. This project helped calibrate our models for the shell molding process with CGI, improving the predictive reliability for future projects involving similar shell castings.

- Iterative Convergence: The optimal process is found through an iterative loop: Design -> Simulate -> Analyze -> Modify. Each loop, whether virtual or physical, refines the understanding of the casting’s thermal behavior.

| Stage | Key Action | Simulation Prediction | Physical Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial Design | Basic risering & gating based on geometry. | Macro directional solidification achieved; micro-shrinkage predicted in riser neck zone. | Confirmed micro-porosity in sectioned casting. | Design insufficient for local thermal geometry. |

| 2. Analysis & Modification | Add contoured internal chill (50x15x15 mm). | Isolated liquid pool eliminated; improved thermal gradient; Niyama criterion indicates soundness. | No micro-porosity detected in critical zone; casting meets specifications. | Chill effectively manages local solidification, enabling riser feed. |

| 3. Validation | Production run with modified process. | N/A | Consistently sound castings. | Process validated and released for production. |

In conclusion, the development of this turbocharger shell casting underscores a modern approach to foundry engineering. By leveraging numerical simulation as a digital crucible, we can virtually explore the complex interplay of fluid flow, heat transfer, and solidification that defines casting quality. This capability is indispensable for mastering the production of intricate, high-performance shell castings, where quality requirements are extreme, and development windows are short. The journey from a digital model to a physically sound casting is one of constant learning and refinement, a process where simulation provides the map, but practical foundry knowledge steers the course.