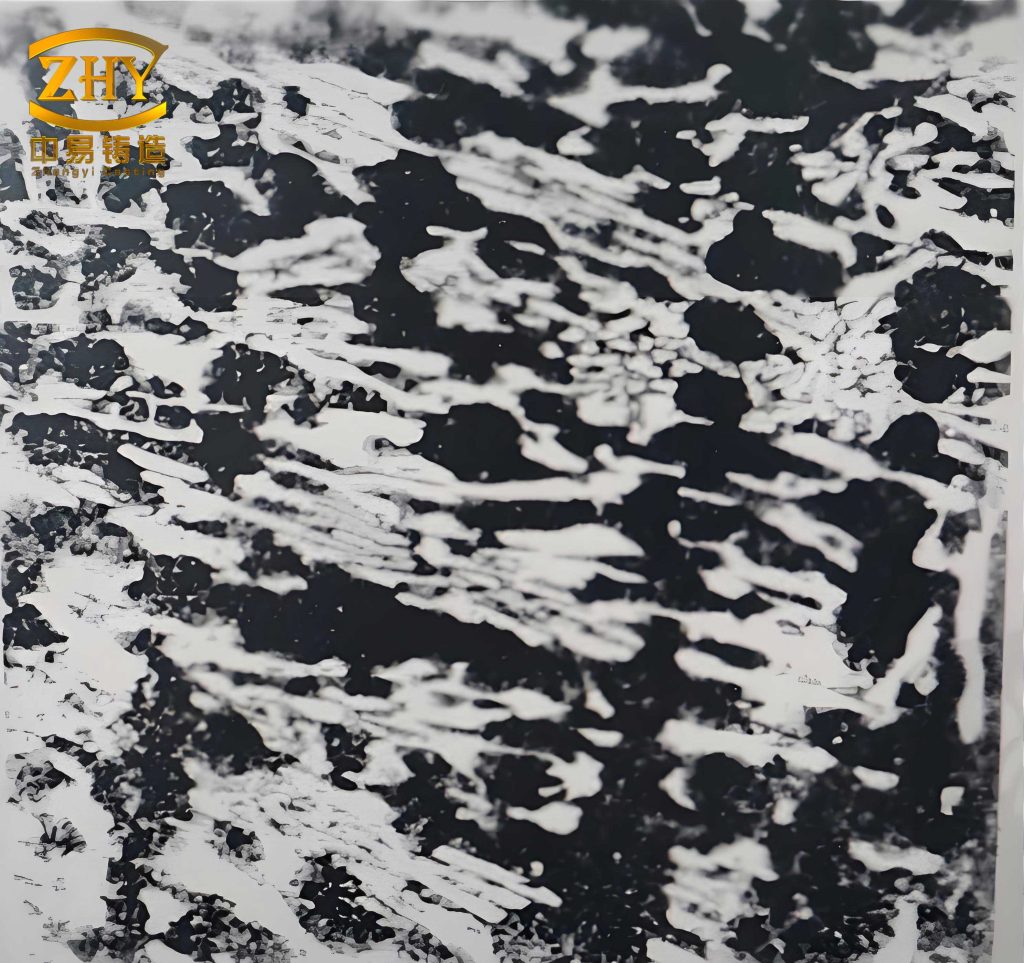

The pursuit of enhanced performance in wear-resistant materials has long driven innovation in ferrous metallurgy. Among these, high-chromium white cast iron stands out for its exceptional abrasion resistance, primarily derived from its hard, chromium-rich carbides embedded within a metallic matrix. However, the inherent brittleness associated with the continuous, often coarse, carbide network in conventional high-chromium white cast iron has been a significant limitation. My extensive work in this field has focused on overcoming this challenge through advanced melt treatment techniques. While modification (or变质处理) is a known method for refining the as-cast structure, I have found that a meticulously designed composite inoculation process can achieve far superior results. This approach builds upon modification to further reduce and eliminate the net-like precipitation of carbides. Under non-equilibrium solidification conditions, it promotes the formation of blocky and granular carbides. This structural shift is paramount, as it substantially improves the strength and toughness of the casting in its as-cast state, reduces internal stresses, and lessens the reliance on subsequent sub-critical heat treatments to adjust the microstructure. The root cause of these transformative changes lies primarily in the kinetic effects generated by the composite inoculation process, both in the high-temperature liquid metal and during its solidification.

The Role of Composite Inoculation

In the metallurgical processing of high-chromium white cast iron, modification and inoculation are two methods that may seem similar but have distinct and focused roles in modifying the material’s properties. In practice, they function synergistically. My methodology involves a “two-step” treatment, performed both inside and outside the furnace. It employs a RE-Ca-Bi-Si (Rare Earth-Calcium-Bismuth-Silicon) composite modifier, with the sequence of graded treatment designed according to the nucleation potency of the modifying alloy’s heterogeneous nuclei. For inoculation, I use a V-slag/Ti-B composite inoculant, again with a graded treatment sequence based on the nucleation energy of the inoculating alloy’s heterogeneous nuclei. Elements such as V (in V-slag form), Mo, and Nb (with W added for large plate castings) are introduced as microalloying elements after pre-deoxidation. The specific functions of this composite inoculation are multifaceted:

- Refinement of Austenite Dendrites: The nucleation and growth of austenite are governed by diffusion kinetics. For a given cooling condition, austenite growth is primarily influenced by solute distribution ahead of the solid/liquid interface. Differences in the segregation tendency of elements lead to variations in the constitutional undercooling at the solidification front. Vanadium and titanium are both positive segregation elements. With a distribution coefficient (k) for V of approximately 0.85 and for Ti of about 0.91, these elements, like the modifying element RE, are potent constitutional undercooling agents. This promotes the refinement of austenite dendrites, alters the morphology of austenite, and results in overall grain refinement in the white cast iron.

- Formation of Blocky Carbides: Both V and Ti are strong carbide-forming elements. It is evident that inoculating particles, composed of vanadium and titanium carbides, exist within the liquid-solid two-phase region during crystallization. During solidification, these particles are sufficient to cause the segregation of carbon atoms, leading to the formation of blocky carbides in subsequent crystallization stages. The roles of V and Ti in composite inoculation are twofold: first, titanium is readily oxidized, sulfidized, and nitrided in the molten iron, thereby protecting vanadium; second, the complex carbides formed by vanadium and titanium are more thermally stable.

- Disruption of Continuous Carbide Networks: The addition of V, Ti, and W (along with potential microalloying elements like Mo and Nb) leads to the development of highly branched austenite dendrites. Subsequent crystallization is then confined within the inter-dendritic spaces, directly influencing the formation and growth of carbides. Furthermore, due to the strong affinity of V and Ti for carbon, while they facilitate heterogeneous nucleation, they also slow down the diffusion rate of carbon in their immediate vicinity. This retards, or even intermittently interrupts, the growth of continuously precipitating carbides. Consequently, this not only strongly suppresses the formation of a continuous, net-like carbide structure but also significantly reduces the overall quantity of such detrimental carbides. Naturally, as the inoculation effect improves, the number of heterogeneous nuclei increases. The inoculation treatment also encourages the precipitation of carbon from austenite to occur preferentially on these existing blocky carbides.

- Promotion of Volume Crystallization: Molten white cast iron treated with inoculation exhibits a greater tendency for undercooling and crystallizes primarily using uniformly distributed exogenous nuclei. Therefore, the influence of cooling rate on the degree of undercooling during crystallization is minimized, and the crystallization process occurs almost simultaneously throughout the entire volume. The engineering significance is profound: the microstructure and properties across the cross-section of thick, heavy-section castings become more uniform and consistent. The primary objectives of implementing this graded treatment for high-chromium white cast iron are: (a) to control the nucleation and growth processes of various modified and inoculated structures, and (b) to enhance the resistance of these structures to fade or “recession.”

Kinetic Effects Governing the Process

The improvements seen are not merely chemical but are fundamentally driven by kinetic phenomena.

Kinetic Effect of Modification

The kinetic effect of the modification treatment using a rare earth composite agent on the subsequent inoculation efficacy manifests in its multi-functional metallurgical role. It must fully and simultaneously perform the following actions during solidification and at high temperatures:

- As a Modifier: Refining austenite grains; controlling the crystallization of austenite and carbides; reducing non-metallic inclusions and altering their morphology.

- As a Deoxidizer, Desulfurizer, and Degasser: Purifying the molten white cast iron, cleansing grain boundaries, and enhancing resistance to fading.

- As a Reductant: Reducing alloy elements that have been oxidized or sulfidized during solidification and at high temperatures, thereby ensuring the metallurgical quality of the modification and other treatment processes, as well as the stability of the resulting solidified structure and morphology.

Kinetic Effect of Composition Design

The selection of carbon (C), silicon (Si), and chromium (Cr) content in the white cast iron melt has a significant kinetic impact on the composite inoculation effect:

- Carbon (C): Carbon is the primary element determining the mechanical properties and wear resistance of high-chromium white cast iron. Excessive carbon leads to large amounts of coarse, networked carbides in the as-cast structure. This is mainly because increased carbon concentration provides a greater probability for concentration fluctuations in the melt, favoring homogeneous nucleation of carbides, which is detrimental to the heterogeneous nucleation and growth of carbides under an inoculated state.

- Silicon (Si): Primarily a deoxidizer, excessive silicon reduces carbon solubility in austenite, increasing carbide precipitation. However, with the implementation of graded rare earth composite modification, the deoxidizing role of silicon is significantly diminished, allowing for a strategic reduction in its content.

- Chromium (Cr): As a “thixotropic element,” an appropriate combination of Cr with C, Ni, Mo, and V can stabilize the formation of a fine, lath-like martensite matrix containing a controlled amount of retained austenite in the as-cast state. During subsequent sub-critical treatment, a partial M残A (secondary carbide) transformation can occur, leading to secondary hardening of the matrix, with finely dispersed secondary carbides distributed within it.

Kinetic Effect of Microalloying

The selection of microalloying elements critically influences the kinetics of composite inoculation. Data from electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) reveals the distribution of elements like Mo, Ti, Nb, and V within the white cast iron matrix.

| Element | Avg. Content in Iron, w% | Austenite Dendrite Core, w% | Austenite Dendrite Edge, w% | Distribution Coefficient, k | Segregation Coefficient, k’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | 0.05 | Trace | 0.02 | ~0.4 | ~0.4 |

| Mo | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.18 | ~0.61 | ~1.64 |

| Nb | 1.33 | 0.33 | 0.48 | ~0.69 | ~1.46 |

| V | 0.93 | 0.26 | 0.29 | ~0.90 | ~1.12 |

The segregation coefficients (k’) for Mo, Ti, Nb, and V are all less than 1 (indicating positive segregation), and their distribution coefficients (k) are also less than 1. This confirms they enrich the liquid ahead of the advancing austenite crystallization front, creating significant constitutional undercooling and thereby promoting the refinement of austenite dendrites. Furthermore, these elements or their related compounds strengthen and stabilize the nucleation and growth of austenite through solid solution effects, increasing the resistance to carbon precipitation from austenite.

Kinetic Effect of Inoculant Composition Design

The kinetic effect of the V-slag/Ti-B inoculant system is central to the process:

- Graded Treatment Sequence: Performing the V-slag/B treatment first, followed by the Ti treatment, reliably ensures the effectiveness of vanadium inoculation. In the initial stage, the low-melting-point B creates a protective boron vapor environment for the V. In the later stage, the more readily oxidized/sulfidized/nitrided Ti effectively shields the vanadium. The resulting complex vanadium-titanium carbides are also more stable.

- Altered Carbon Precipitation Mode: After inoculation, the mode of carbon precipitation changes from continuous precipitation to predominantly discontinuous precipitation based on heterogeneously nucleated blocky carbides, sometimes appearing as lamellar carbides. This is because the nucleation resistance for this type of precipitate in the solid state is low. From an engineering standpoint, this effectively solves the problem of the strongly networked growth tendency of carbides caused by continuous precipitation.

Kinetic Effect of Interface Perturbation

During crystal growth, disturbances at the moving solid/liquid interface are inevitable. The kinetic theory of interface stability, fundamentally studies how the amplitude and frequency of such perturbations affect stability. In modern terms, considering the wave-particle duality of matter, discussing the kinetic effect of interface disturbance on composite inoculation efficacy ultimately involves analyzing how changes in the external force field and temperature field at the interface front influence the nucleation and growth rates of heterogeneous nuclei. If we consider the crystallization interface of untreated white cast iron melt as an undisturbed state—a plane moving at constant velocity—its equation in a moving coordinate system is $z=0$. When the melt undergoes modification, inoculation, and microalloying, it inevitably induces changes near the interface, causing thermal and solutal disturbances (and under special conditions, force disturbances). The interface equation can be described (expanded as a sine wave) as:

$$ z(x,t) = \zeta(x,t) = \zeta(t) \sin(\omega x) $$

where $\zeta(t)$ is the perturbation amplitude and $\omega$ is the angular frequency. Typically, after a period, the disturbance amplitude relates to time exponentially: $\zeta(t) = \text{constant} \cdot e^{\beta t}$. Therefore:

$$ \frac{d \ln(\zeta(t))}{dt} = \frac{1}{\zeta(t)} \cdot \frac{d\zeta}{dt} = \beta $$

The behavior of the disturbance in the potential field depends on the value of $\beta$. If $\beta > 0$, the disturbance amplitude grows with time, and the interface is unstable. If $\beta < 0$, the amplitude decays, and the interface stabilizes. The magnitude of $\beta$ determines the rate of growth or decay. This concept not only describes the kinetic effect of disturbances using wave properties but can also be viewed from the perspective of particle motion at the interface. Disturbances arising during metallurgical treatment are objective realities and can be altered by different process parameters and methods. The interface perturbation caused by inoculation reflects its objective effectiveness. Controlling and modifying the resulting kinetic effects can either enhance or diminish the impact of interface disturbance on the composite inoculation outcome. Under conditions involving centrifugal or other external forces (excluding gravity) that cause vibration or agitation of the white cast iron melt during casting, the relationship between pressure and nucleation rate ($I$) can be derived as:

$$ I = A \exp\left[ -\frac{B}{(\Delta T_r)^2} – C \Delta P \right] $$

Taking the logarithm yields:

$$ \ln I = \ln A – \frac{B}{(\Delta T_r)^2} – C \Delta P $$

where $\Delta P$ is the pressure, and $A$, $B$, $C$ are constants. This relationship indicates that, within a certain range, increasing pressure during solidification can refine the grain structure. Therefore, generally speaking, dynamic non-equilibrium crystallization makes the divorced eutectic phenomenon and the suppression of continuous networks even more pronounced.

Practical Application and Results

The efficacy of the composite inoculation process is unequivocally demonstrated by the enhancement in mechanical properties. The following table compares the as-cast properties of treated versus conventional high-chromium white cast iron.

| Inoculation State | Hardness, HRC | Impact Toughness, ak (J/cm²) | Bending Strength, σbb (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Inoculated | 58 | 5.0 | ~430 |

| Composite Inoculated | 62 | 9.0 | ~530 |

The data shows a marked improvement in all key mechanical properties. The increase in hardness is accompanied by a near-doubling of impact toughness and a significant rise in bending strength, directly addressing the traditional toughness deficit of white cast iron.

Conclusion

Implementing composite inoculation in high-chromium white cast iron represents a crucial technological pathway for elevating its metallurgical quality. The systematic metallurgical treatment described herein yields an as-cast microstructure and mechanical properties that provide the necessary technical foundation for replacing the traditional high-temperature austenitizing treatment of high-chromium white cast iron with a sub-critical heat treatment process. This advancement further reduces casting internal stresses, lowers production costs, and shortens the manufacturing cycle. The tangible benefits imparted by composite inoculation to the white cast iron melt are, in essence, the inevitable result of the systematic kinetic effects generated by comprehensive metallurgical treatment, influencing the melt both at high temperature and throughout the solidification process. The transformation from a brittle, networked carbide structure to a tough, refined dispersion of blocky carbides exemplifies the power of harnessing kinetics in the metallurgy of white cast iron.