For a significant period, the prevailing approach in many domestic production facilities for machine tool castings has been guided by a common standard: mechanical properties serve as the acceptance criterion, while chemical composition is not, unless specified in a contract. This has led to a widespread misconception. Since strength is the primary metric, achieving it through the reduction of Carbon Equivalent (CE) appeared to be the most straightforward path. Consequently, a generation of machine tool castings was produced under a paradigm of low CE and high strength. However, extensive industrial practice and research have revealed that this approach carries substantial negative impacts on the ultimate performance and reliability of precision machine tools.

The issues stemming from low CE and high strength are multifaceted and interconnected:

- Increased Shrinkage: Lower CE elevates the tendency for shrinkage porosity and cavities, compromising casting integrity.

- Elevated Residual Stress: This is a critical drawback, leading to poor dimensional stability, a higher risk of cracking, and significantly undermining the machine’s precision retention.

- Poor Fluidity: Hinders the filling of thin sections, acting as a barrier to the design trend of casting lightweighting and thin-wall structures.

- Deteriorated Machinability: Results in reduced cutting speeds and shorter tool life, increasing manufacturing costs and time.

- Inferior Damping Capacity: Adversely affects achieved machining accuracy and its stability during operation.

- Poor Quality Consistency: The aforementioned problems tend to recur unpredictably, making stable, high-quality production challenging. Surveys consistently indicate that inconsistent quality is a top concern among end-users.

The evolution of modern manufacturing, particularly the advent of high-precision, high-speed, and heavy-duty CNC machine tools for aerospace, defense, energy, and automotive sectors, has rendered the old paradigm obsolete. The new core requirements for advanced machine tool castings are unequivocally: High Carbon Equivalent, High Strength, High Rigidity (Stiffness), and Low Stress. This quartet of properties represents a sophisticated balance essential for next-generation performance.

The Imperative for High Rigidity and Damping in Precision

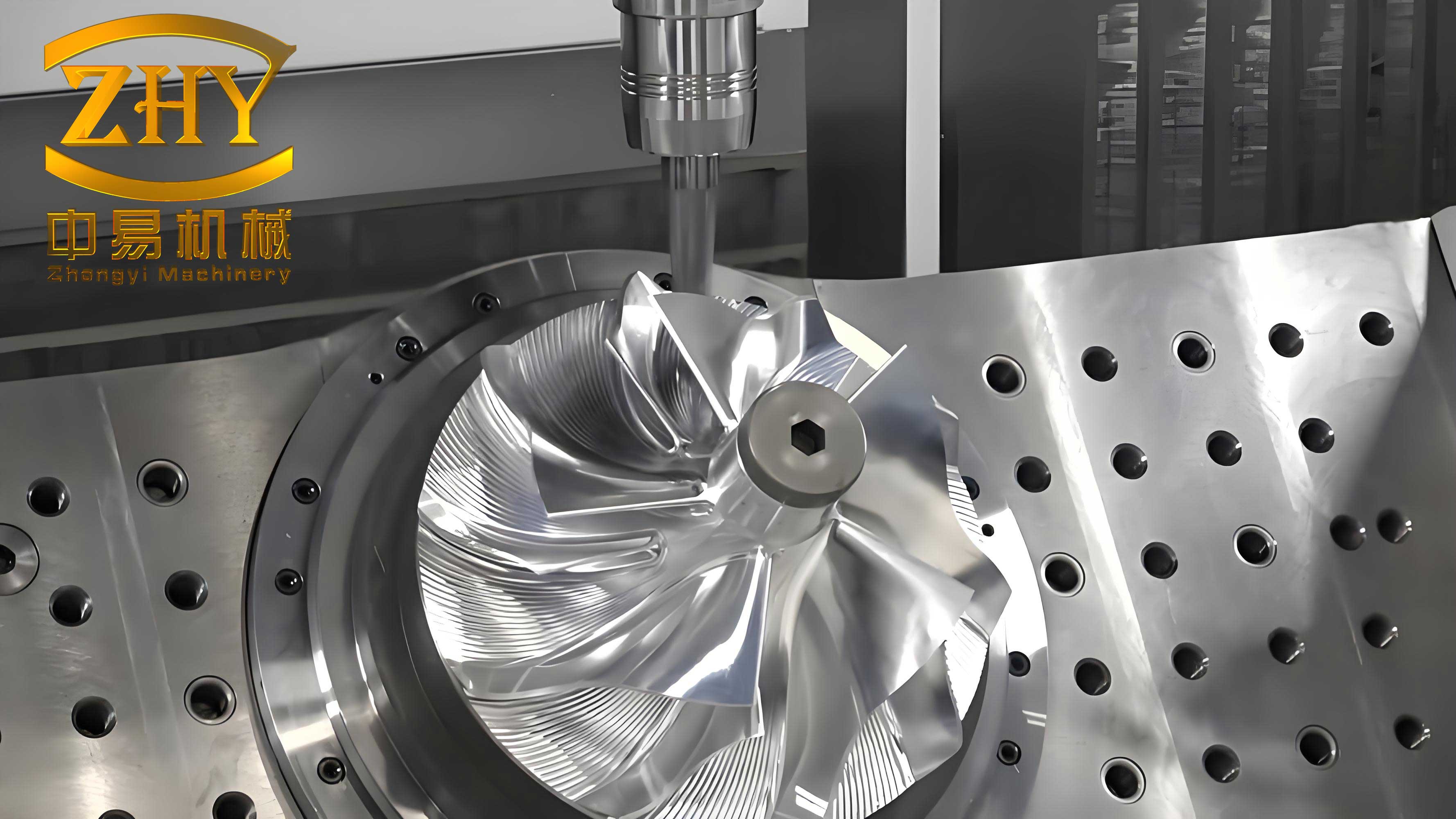

Modern CNC machining often involves cutting “sticky” and “hard” advanced alloys at high speeds and with significant force. While the strength of a casting typically has a large safety factor against these loads, its resistance to deformation—its rigidity—is paramount. In many cases, critical machine tool castings are designed based on stiffness requirements rather than pure strength. Rigidity, quantified by Young’s Modulus (E), is primarily dependent on tensile strength. Therefore, high-strength grades like HT300, HT350, and high-strength ductile iron are specified.

However, maintaining precision under dynamic cutting conditions also requires excellent damping capacity to absorb vibrations. Here lies a classic conflict: high rigidity often pushes for lower CE, while superior damping is favored by higher CE. The key innovation is to break this traditional trade-off. The goal for premium machine tool castings is to achieve high strength and, consequently, high rigidity at a high Carbon Equivalent. This reconciles the need for formidable resistance to deformation with the essential property of vibration absorption.

Precision Retention: The Critical Role of Low Residual Stress

Precision retention is arguably the most crucial differentiator for high-end CNC machine tools. A major factor influencing long-term dimensional stability is the residual stress locked within the casting after solidification and cooling. This intrinsic stress is often more dangerous than operational loads because it is persistent and can cause gradual, irreversible plastic deformation over time.

Research establishes a clear correlation: residual stress increases as Carbon Equivalent decreases and as tensile strength increases (for a given metallurgical approach). Therefore, the prevalent method of achieving high strength via low CE inherently leads to high residual stress. This has been a persistent weakness, sometimes leading international customers to subject purchased castings to long-term natural aging before use. The new direction directly addresses this: achieving high strength through means that allow for a higher CE, thereby inherently reducing residual stress and enhancing the precision retention of the final machine.

Machinability and Castability: Enabling Efficient Production

The manufacturing of machine tool castings themselves has evolved. Complex, thin-walled structures are machined on high-speed machining centers with spindle speeds reaching tens of thousands of RPM. This demands excellent machinability from the casting material. Low CE, while boosting strength, also raises hardness (HBW), deteriorating machinability.

A useful metric for machinability is the ratio \( m \), defined as:

$$ m = \frac{R_m}{HBW} $$

where \( R_m \) is the tensile strength (MPa) and \( HBW \) is the hardness. A higher \( m \) value indicates better machinability for a given strength level. Achieving high strength with a higher CE generally results in a lower hardness, thus a higher \( m \) value and superior machinability.

Furthermore, casting properties are enhanced. Higher CE improves molten metal fluidity, enabling the successful pouring of complex, thin-walled designs. It also reduces both solidification shrinkage (minimizing shrinkage defects) and solid-state contraction (reducing dimensional variation and stress). This is essential for producing lighter, more rigid castings with fewer internal defects.

The Current State: Survey Insights on Domestic Production

Recent surveys of domestic producers reveal both progress and persistent gaps. The focus has been on the prevalent HT300 grade, analyzing statistics from 60 consecutive melts per foundry.

Carbon Equivalent and Strength: The data shows a positive trend towards higher CE values at the HT300 strength level compared to surveys from five years prior.

| CE Range (%) | Approx. Avg. CE (%) | Proportion of Foundries (2009 Survey) | Proportion of Foundries (Recent Survey) |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 3.60 | ~3.52 | 45.5% | 15.4% |

| 3.64 – 3.68 | ~3.65 | 36.3% | 46.2% |

| 3.70 – 3.76 | ~3.71 | 18.2% | 38.4% |

While the average CE has improved from ~3.60% to ~3.67%, a significant gap remains compared to the international benchmark of approximately 3.83% CE for HT300. This gap manifests in production challenges. When asked about the main difficulties in producing high-end machine tool castings, foundries reported:

| Reported Difficulty | Percentage of Foundries Citing |

|---|---|

| Complex Structure | 71% |

| Prone to Distortion | 50% |

| Shrinkage Porosity | 50% |

Notably, failing to meet mechanical specifications was a minor issue (<7%). The primary challenges are directly linked to the consequences of low CE: poor fillability of complex structures, high stress leading to distortion, and increased shrinkage tendency.

Metallurgical Quality Indicators: Two key derived metrics are essential for judging the quality of machine tool castings:

- Relative Hardness (RH) or Hardening Degree (HG): Indicates machinability. \( HG < 1 \) is desirable.

$$ HG = \frac{HBW_{measured}}{(530 – 344 \cdot S_c)} \quad \text{(for HBW ≤ 186)} $$

$$ HG = \frac{HBW_{measured}}{(930 – 744 \cdot S_c)} \quad \text{(for HBW > 186)} $$

where \( S_c \) is the degree of saturation (carbon equivalent relative to the eutectic point). - Quality Index (QI): A composite metric. \( Q_I > 1 \) indicates good overall metallurgical quality, often associated with higher CE at a given strength.

$$ Q_I = \frac{RG}{HG} \quad \text{where} \quad RG = \frac{R_m}{(1000 – 800 \cdot S_c)} $$

\( RG \) is the maturity degree, with \( RG > 1 \) being favorable.

Survey data contrasting different foundries producing HT300 vividly illustrates the impact of CE:

| Foundry Type | Avg. CE (%) | Avg. Rm (MPa) | Avg. HBW | Machinability Index \( m \)** | Quality Index \( Q_I \)** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-CE Producer A | 3.57 | 365 | 264 | 1.38 | 0.99 |

| Low-CE Producer B | 3.59 | 319 | 244 | 1.30 | 0.94 |

| High-CE Producer C | 3.76 | 311 | 196 | 1.58 | 1.18 |

| High-CE Producer D | 3.72 | 328 | 192 | 1.70 | 1.27 |

** Calculated from average values for illustration.

The high-CE producers achieve excellent strength with significantly lower hardness, leading to superior machinability (\( m \) > 1.5) and a quality index well above 1.0. Reports indicate such castings have excellent machinability and rarely suffer from shrinkage cracks.

Key Technologies for Achieving the New Paradigm

Transitioning to the production of high-CE, high-strength, low-stress machine tool castings requires a holistic and controlled approach across the entire process chain.

1. Chemical Composition and Charge Design: Precise control is non-negotiable. The aim is to use high steel scrap ratios with effective carburization to achieve the target high-C/high-Si chemistry without relying on low-CE pig iron.

| Grade | Target CE (%) | Steel Scrap (%) | Returns (%) | Pig Iron (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT250 | 3.90 – 3.95 | 50 – 55 | 40 – 45 | < 10 |

| HT300 | 3.80 – 3.85 | 60 – 70 | 30 – 35 | < 5 |

| HT350 | 3.75 – 3.80 | 70 – 80 | 20 – 30 | 0 |

2. High-Temperature, Low-Oxidation Melting and Inoculation: A high superheat temperature (e.g., 1510-1540°C for HT300) followed by a brief holding period (7-10 min) is crucial for obtaining a pure, homogeneous molten iron with good inherent properties. Effective inoculation is then paramount to control the graphite structure and prevent chill. A combination of methods (e.g., in-stream + late-stream inoculation) using preheated FeSi or specialized inoculants (e.g., Si-Ba-Ca) is recommended to combat fade.

3. Controlled Solidification and Cooling: The shakeout temperature from the mold has a direct impact on residual stress. A lower shakeout temperature (e.g., below 300°C) is strongly advised to minimize locked-in thermal stresses.

4. Rigorous Stress Relief Annealing: Thermal aging is essential for high-stability machine tool castings. The process must be carefully controlled:

- Heating/Cooling Rate: 30-50°C/h for large/complex castings.

- Soak Temperature: 550-590°C for HT300/HT350.

- Soak Time: Based on section thickness (e.g., ~1 hour per 25 mm).

- Furnace Uniformity: Temperature variation within ±20°C is critical.

- Proper Loading: Castings must be supported to prevent sagging at temperature.

Well-executed thermal aging can reduce residual stress by 40-70%. It should ideally be performed after rough machining.

5. Monitoring Advanced Properties: Moving beyond just tensile strength, leading-edge producers should monitor:

- Young’s Modulus (E): Target >125 GPa for HT300, >135 GPa for HT350.

- Residual Stress: Target <50 MPa in critical castings after aging (measured via strain-gauge techniques on representative sections or actual castings).

The simultaneous achievement of high CE, high Rm, high E, and low residual stress is the definitive mark of quality for advanced machine tool castings.

Conclusion

The development direction for high-end CNC precision machine tool castings is unequivocal. The outdated model of trading carbon equivalent for strength must be abandoned. The future lies in the integrated pursuit of High Carbon Equivalent, High Strength, High Rigidity, and Low Residual Stress. This paradigm shift addresses the fundamental requirements of modern machine tools: exceptional static and dynamic stiffness for accuracy under load, superior damping for stability, excellent machinability for economic production, and inherent dimensional stability for long-term precision retention. Achieving this requires a sophisticated synthesis of charge design, high-temperature melting, advanced inoculation, controlled cooling, and precise thermal processing. The foundries that master this integrated technological suite will be the ones producing the foundational components for the world’s most capable and reliable precision machine tools.