In the manufacturing of machine tool castings, the metallurgical quality of molten iron plays a pivotal role in determining the final product’s performance, including strength, dimensional stability, vibration damping, and machinability. As a foundry engineer involved in producing high-precision components, I have observed that many domestic machine tool castings suffer from issues related to low carbon equivalent, which adversely affects their properties. This article delves into how optimizing molten iron metallurgy through improved melting equipment and materials can enhance the quality of machine tool castings, reduce defects, and lower rejection rates. By sharing our experiences and data, I aim to highlight the critical factors that influence the metallurgical quality and, consequently, the performance of machine tool castings in industrial applications.

The foundation of producing high-quality machine tool castings lies in understanding the relationship between iron composition, melting processes, and the resulting microstructure. Grey iron, commonly used for machine tool castings, derives its mechanical properties from a combination of graphite morphology and matrix structure. Key metallurgical quality indicators, such as maturity (RG), relative hardness (RH), and quality coefficient (Qi), provide insights into the iron’s behavior. For instance, RG is defined as the ratio of actual tensile strength to theoretical tensile strength, calculated as:

$$RG = \frac{\sigma_{\text{actual}}}{\sigma_{\text{theoretical}}}$$

Similarly, RH represents the ratio of actual hardness to theoretical hardness:

$$RH = \frac{HB_{\text{actual}}}{HB_{\text{theoretical}}}$$

And Qi is derived as the ratio of RG to RH:

$$Qi = \frac{RG}{RH}$$

Higher values of RG and Qi indicate superior metallurgical quality, which is essential for achieving the desired properties in machine tool castings without resorting to low carbon equivalents that can lead to casting defects.

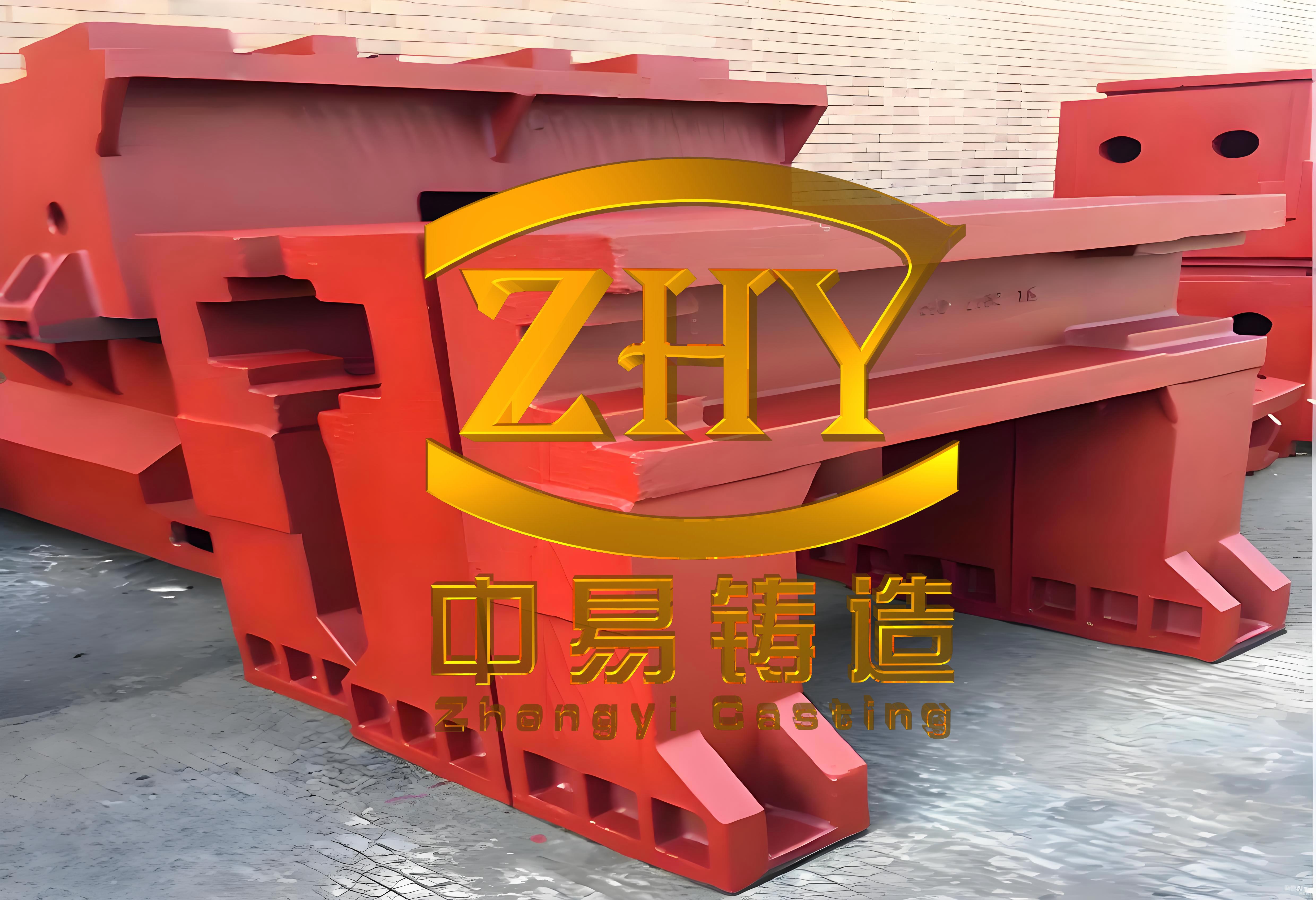

In our initial production setup, we faced significant challenges with machine tool castings, such as the X5032-17021 worktable and its base, which are critical components in CNC machines. These machine tool castings were made from HT250 grade grey iron, with weights of 298 kg and 256 kg, respectively. We employed sand casting with furan resin sand for molds and cores, often producing two pieces per mold box. However, the use of small-capacity cupolas (5 t/h) and low-quality local coke resulted in suboptimal iron metallurgy, leading to defects like shrinkage porosity and cracks. The carbon equivalent (CE) was kept low to meet strength requirements, but this approach compromised casting performance. The carbon equivalent is calculated as:

$$CE = C + \frac{Si + P}{3}$$

Where C, Si, and P are the weight percentages of carbon, silicon, and phosphorus, respectively. In our case, the low CE increased the undercooling tendency, reducing graphite expansion during eutectic transformation and elevating shrinkage risks. The table below summarizes the charge mixture used in the original process for producing these machine tool castings:

| Heat | Pig Iron | Steel Scrap | Returns | 75% FeSi | 65% FeMn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-38 | 180 | 260 | 160 | 7 | 16 |

| 2005-39 | 120 | 310 | 170 | 6 | 17 |

| 2005-40 | 230 | 220 | 150 | 7 | 17 |

| 2005-41 | 130 | 300 | 170 | 8 | 17 |

| 2005-46 | 200 | 240 | 160 | 6 | 17 |

| 2005-47 | 180 | 280 | 140 | 6 | 15 |

| 2005-49 | 180 | 240 | 180 | 6 | 16 |

The chemical composition of the iron from these heats is presented in the following table, showing variations that affected the consistency of machine tool castings:

| Heat | C | Si | Mn | P | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-38 | 3.23 | 1.96 | 1.00 | 0.081 | 0.090 |

| 2005-39 | 3.07 | 1.45 | 0.67 | 0.074 | 0.105 |

| 2005-40 | 2.82 | 1.60 | 0.78 | 0.084 | 0.129 |

| 2005-41 | 3.04 | 1.63 | 0.77 | 0.072 | 0.116 |

| 2005-46 | 2.94 | 1.59 | 1.13 | 0.076 | 0.122 |

| 2005-47 | 3.13 | 1.76 | 1.03 | 0.076 | 0.095 |

| 2005-49 | 3.04 | 1.77 | 1.11 | 0.094 | 0.120 |

Carburization was a critical aspect, as the low-quality coke led to inadequate carbon pickup, averaging only 45.1% across heats, as shown below:

| Heat | Input Carbon (%) | Final Carbon (%) | Carburization Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-38 | 2.16 | 3.23 | 49.5 |

| 2005-39 | 1.83 | 3.07 | 67.8 |

| 2005-40 | 2.42 | 2.82 | 16.5 |

| 2005-41 | 1.83 | 3.04 | 66.1 |

| 2005-46 | 2.28 | 2.94 | 28.9 |

| 2005-47 | 2.06 | 3.13 | 51.9 |

| 2005-49 | 2.25 | 3.04 | 35.1 |

The metallurgical quality and mechanical properties of the original machine tool castings were subpar, with an average RG of 0.859, RH of 0.954, and Qi of 0.903, indicating poor iron quality. The low maturity and high relative hardness resulted in increased white iron tendency, with chill widths of 4–9 mm after inoculation, and microstructures showing fine flake graphite in a pearlitic matrix. This led to significant rejection rates due to defects, as summarized in the table below:

| Casting Name | Shrinkage Porosity | Shrinkage Cavities | Gas Holes | Other Defects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X5032 Worktable Base | 40 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| X6132 Worktable | 5 | 20 | 3 | 2 |

To address these issues, we overhauled our melting process by adopting larger cupolas (10 t/h and 7 t/h) and high-quality cold-pressed formed coke, which significantly improved the metallurgical quality of the molten iron for machine tool castings. The larger cupola provided better thermal stability and higher carburization rates, while the superior coke ensured consistent temperatures and reduced oxidation. The charge mixture was adjusted to include more steel scrap and less pig iron, enhancing the iron’s homogeneity and graphite formation. The table below details the new charge mixture:

| Heat | Pig Iron | Steel Scrap | Returns | 75% FeSi | 65% FeMn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-017 | 230 | 450 | 320 | 13 | 9 |

| 2008-019 | 190 | 450 | 360 | 14 | 9 |

| 2008-023 | 240 | 420 | 340 | 10 | 9 |

| 2008-042 | 250 | 500 | 250 | 12 | 10 |

| 2008-043 | 200 | 500 | 300 | 11 | 10 |

| 2008-044 | 200 | 400 | 400 | 10 | 10 |

| 2008-046 | 160 | 520 | 320 | 14 | 11 |

| 2008-048 | 160 | 540 | 300 | 12 | 8 |

| 2008-050 | 100 | 540 | 360 | 8 | 10 |

| 2008-051 | 100 | 560 | 340 | 8 | 10 |

| 2009-007 | 100 | 500 | 400 | 13 | 9 |

| 2009-010 | 200 | 500 | 300 | 13 | 9 |

| 2009-012 | 120 | 520 | 360 | 13 | 9 |

The chemical composition became more consistent, with higher carbon equivalents, as shown in the following table:

| Heat | C | Si | Mn | P | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-017 | 2.89 | 2.24 | 0.81 | 0.045 | 0.123 |

| 2008-019 | 3.26 | 1.86 | 0.78 | 0.052 | 0.086 |

| 2008-023 | 2.94 | 2.13 | 0.82 | 0.060 | 0.160 |

| 2008-042 | 3.27 | 1.96 | 0.71 | 0.072 | 0.172 |

| 2008-043 | 2.85 | 2.12 | 0.85 | 0.064 | 0.104 |

| 2008-044 | 3.11 | 1.86 | 0.75 | 0.054 | 0.127 |

| 2008-046 | 3.08 | 1.38 | 0.78 | 0.060 | 0.102 |

| 2008-048 | 3.40 | 1.53 | 0.69 | 0.059 | 0.119 |

| 2008-050 | 3.26 | 1.47 | 0.73 | 0.048 | 0.112 |

| 2008-051 | 3.09 | 1.49 | 0.87 | 0.049 | 0.095 |

| 2009-007 | 3.13 | 1.66 | 0.98 | 0.048 | 0.103 |

| 2009-010 | 3.22 | 1.47 | 0.79 | 0.037 | 0.076 |

| 2009-012 | 3.18 | 1.62 | 0.79 | 0.040 | 0.092 |

Carburization rates improved dramatically, averaging 68.76%, due to the better coke and larger cupola, as detailed below:

| Heat | Input Carbon (%) | Final Carbon (%) | Carburization Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-017 | 2.04 | 2.89 | 41 |

| 2008-019 | 2.01 | 3.26 | 62 |

| 2008-023 | 2.14 | 2.94 | 37 |

| 2008-042 | 1.93 | 3.27 | 69 |

| 2008-043 | 1.88 | 2.85 | 60 |

| 2008-044 | 2.16 | 3.11 | 44 |

| 2008-046 | 1.79 | 3.08 | 72 |

| 2008-048 | 1.73 | 3.40 | 97 |

| 2008-050 | 1.68 | 3.26 | 94 |

| 2008-051 | 1.62 | 3.09 | 91 |

| 2009-007 | 1.79 | 3.13 | 74 |

| 2009-010 | 1.88 | 3.22 | 71 |

| 2009-012 | 1.75 | 3.18 | 82 |

The metallurgical quality indicators showed remarkable improvement, with an average RG of 1.04, RH of 0.9, and Qi of 1.16, indicating enhanced iron quality for machine tool castings. The chill width reduced to 0–3 mm after inoculation, and microstructures exhibited well-distributed A-type graphite in a pearlitic-sorbitic matrix. This translated into lower rejection rates, as shown in the table below:

| Casting Name | Shrinkage Porosity | Shrinkage Cavities | Gas Holes | Other Defects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X5032 Worktable Base | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| X6132 Worktable | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

The improvement in metallurgical quality allowed us to increase the carbon equivalent while maintaining or even enhancing tensile strength, which is crucial for machine tool castings. The relationship between carbon equivalent and tensile strength can be expressed empirically as:

$$\sigma_{\text{theoretical}} = k \cdot (CE – C_{\text{min}})$$

Where k is a constant dependent on cooling rate and inoculation, and C_min is the minimum carbon for graphite formation. In our case, higher CE promoted better graphite expansion, reducing shrinkage and improving casting soundness. Additionally, the use of high-quality coke and larger cupolas enabled higher tapping temperatures (1,450–1,500°C), which minimized oxidation and improved fluidity, further benefiting the production of complex machine tool castings.

In conclusion, the metallurgical quality of molten iron is a decisive factor in the performance and reliability of machine tool castings. By transitioning to larger melting equipment and superior coke, we achieved higher carburization rates, improved graphite morphology, and enhanced mechanical properties without compromising carbon equivalent. This approach not only reduced defects like shrinkage and porosity but also optimized machinability and dimensional stability. For foundries producing machine tool castings, focusing on iron metallurgy through advanced melting practices is essential for meeting the demanding requirements of modern CNC machinery. Future efforts should continue to explore innovations in charge materials, inoculation techniques, and process control to further elevate the quality of machine tool castings in global markets.