In the field of industrial manufacturing, machine tool castings play a critical role in ensuring the durability and precision of heavy machinery. As a casting engineer with extensive experience, I have encountered numerous challenges in producing high-quality machine tool castings, particularly when dealing with complex geometries and large-scale components. This article delves into two detailed case studies where innovative casting techniques were applied to overcome defects such as shrinkage and gas porosity, ultimately improving product quality and reducing costs. Through these examples, I will share insights on process optimization, the integration of mathematical models, and practical adjustments that can significantly enhance the performance of machine tool casting operations. The focus will remain on machine tool casting and machine tool castings, as these are central to advancing manufacturing capabilities.

The first case involves the production of a rear lining plate, a common machine tool casting used in heavy equipment. Initially, the casting process relied on traditional methods with ceramic tubes for the gating system and multiple insulation risers. However, this approach resulted in a high rejection rate of 20% to 30%, primarily due to shrinkage and gas pores at the riser roots. After thorough analysis, we identified several issues: inadequate venting, excessive gas generation from resin sand, and suboptimal pouring parameters. To address these, we redesigned the gating system by adding six inner gates around the outer edge, an overflow channel, and vent holes to facilitate better gas escape. Additionally, we incorporated a single larger insulation riser and implemented pre-heating of the mold at 200°C for one hour to reduce moisture and gas evolution. The pouring temperature was carefully controlled between 1,370°C and 1,390°C, with a brief holding time in the ladle to allow for slag removal. These modifications led to a dramatic reduction in defects, lowering the rejection rate to below 2% and increasing the process yield from 62% to 70%. A comparative table summarizes the outcomes, highlighting the efficiency gains.

| Process | Molding Time (min) | Rejection Rate Due to Shrinkage/Gas Porosity | Process Yield (%) | Cleaning and Grinding Time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Process | 40-50 | Approximately 30% | 62 | 6 |

| Improved Process | 25-35 | Approximately 2% | 70 | 2 |

To further illustrate the thermal dynamics involved in machine tool casting, we can apply Chvorinov’s rule, which estimates the solidification time of a casting. The formula is given by: $$ t = B \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^2 $$ where \( t \) is the solidification time, \( V \) is the volume of the casting, \( A \) is the surface area, and \( B \) is a constant dependent on the mold material and casting conditions. For instance, in the improved process, the reduced riser size and optimized gating altered the \( V/A \) ratio, leading to faster and more uniform solidification, thereby minimizing shrinkage defects. This mathematical approach is essential for predicting and controlling the quality of machine tool castings.

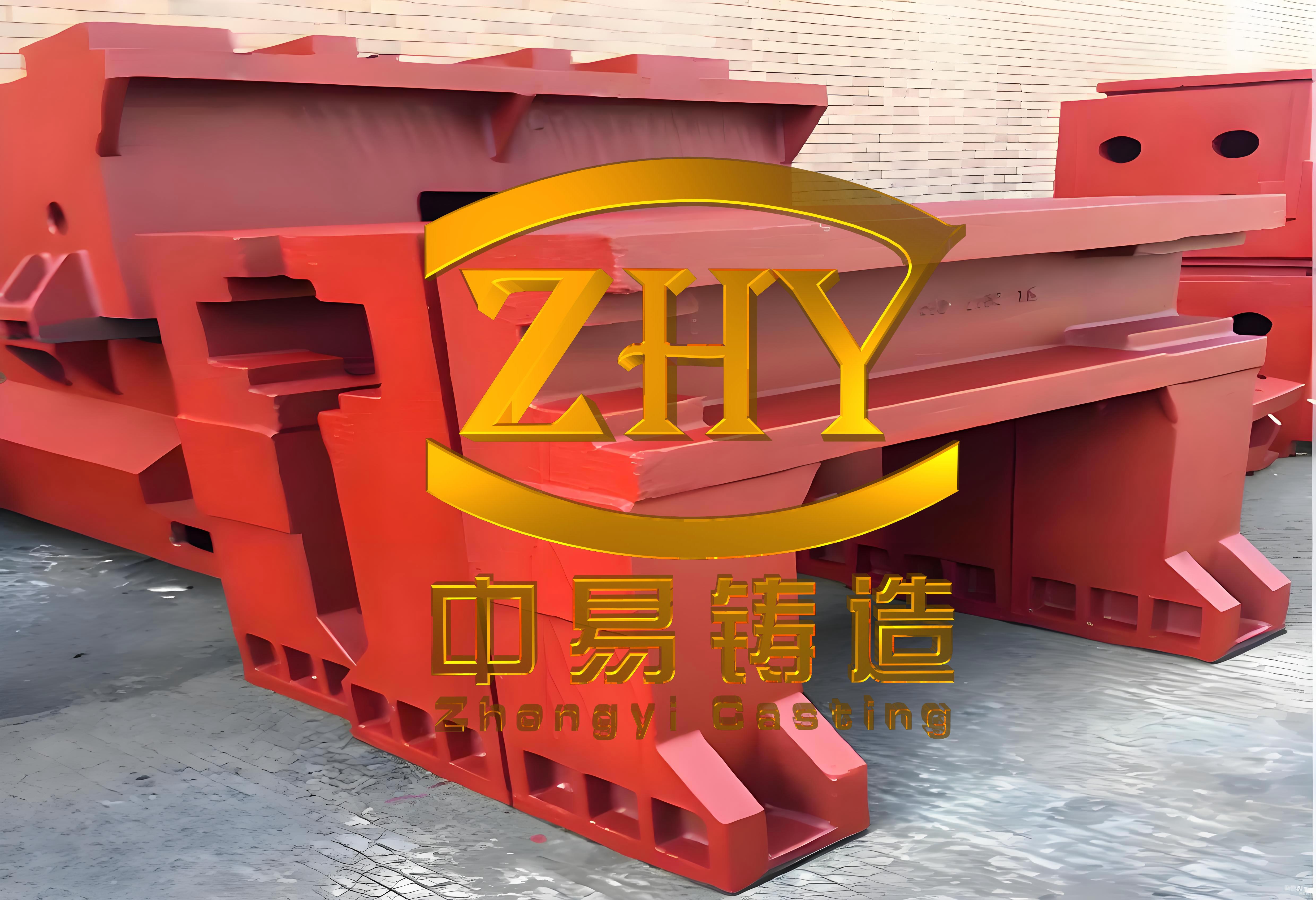

The second case study focuses on the production of a large machine tool casting—specifically, a column for a machine tool with dimensions of 7,800 mm × 1,800 mm × 2,600 mm and a weight of 36 tons. This machine tool casting required a single-piece production, making traditional pattern-making methods costly and time-consuming. We adopted the lost foam casting process, which involved creating a foam pattern from expandable polystyrene sheets. The pattern was coated with a water-based graphite coating having a Baume degree of 60-70, and it was dried at 50-60°C for 24 hours to ensure sufficient strength. During molding, we used a sandbox and incorporated iron core bones to reinforce the mold. The gating system consisted of multiple layers with ceramic tubes for the sprue and foam for the runners, following an open gating ratio of \( \sum F_{\text{sprue}} : \sum F_{\text{runner}} : \sum F_{\text{gate}} = 1.0 : 1.5 : 4.0 \). Pouring was performed at 1,380-1,400°C with a fast pouring rate to reduce gas entrapment. Post-casting, the component exhibited excellent surface finish, minimal deformation of about 5 mm, and met the required mechanical properties, such as a tensile strength of 315 MPa and hardness of 210 HB. Cost analysis revealed that the lost foam method reduced pattern costs by 90% compared to wooden patterns and decreased finishing labor by 70-80%, demonstrating its viability for large machine tool castings.

In both cases, the control of process parameters was paramount. For example, the heat transfer during solidification can be modeled using Fourier’s law of heat conduction: $$ q = -k \nabla T $$ where \( q \) is the heat flux, \( k \) is the thermal conductivity, and \( \nabla T \) is the temperature gradient. In machine tool casting, optimizing these gradients through mold design and pouring techniques helps prevent defects like cold shuts or misruns. Additionally, the gas evolution in resin-bonded sands can be quantified by the relationship: $$ G = \alpha \cdot e^{-\beta / T} $$ where \( G \) is the gas volume, \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \) are constants, and \( T \) is the temperature. By pre-heating molds, we reduced \( G \), thereby minimizing gas porosity in the final machine tool castings.

Another critical aspect is the economic evaluation of casting processes. The overall cost efficiency for machine tool casting can be expressed as: $$ C_{\text{total}} = C_{\text{material}} + C_{\text{labor}} + C_{\text{energy}} + C_{\text{rework}} $$ where each component depends on process choices. For instance, the improved process in the first case reduced \( C_{\text{rework}} \) significantly, while the lost foam method in the second case lowered \( C_{\text{material}} \) and \( C_{\text{labor}} \). The table below extends the comparison to include cost factors, emphasizing the importance of holistic optimization in machine tool casting operations.

| Process Type | Material Cost Saving | Labor Cost Saving | Energy Consumption | Overall Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Sand Casting | Base | Base | High | 0% |

| Improved Gating Process | 10-15% | 20-30% | Moderate | 25-40% |

| Lost Foam Casting | 70-90% | 70-80% | Low | 60-80% |

Furthermore, the mechanical properties of machine tool castings, such as hardness and tensile strength, are influenced by the cooling rate and composition. The relationship between cooling rate \( R \) and secondary dendrite arm spacing \( \lambda \) can be described by: $$ \lambda = k R^{-n} $$ where \( k \) and \( n \) are material constants. In our practices, controlling \( R \) through mold materials and pouring parameters ensured that the machine tool castings achieved the desired microstructure and performance. For example, in the large column casting, the use of low-alloy配料 and controlled pouring temperatures resulted in a homogeneous structure with minimal internal stresses.

In conclusion, the evolution of machine tool casting techniques underscores the need for continuous process refinement. From adjusting gating systems to adopting innovative methods like lost foam casting, each step contributes to higher quality and efficiency. Mathematical models and empirical data, as shared in this article, provide a foundation for predicting outcomes and making informed decisions. As I reflect on these experiences, it is clear that a proactive approach—monitoring process adherence and swiftly addressing issues—is crucial for success in producing reliable machine tool castings. The integration of tables and formulas not only aids in analysis but also serves as a guide for future projects, ensuring that machine tool casting remains a cornerstone of advanced manufacturing.