In my experience working in a foundry, I have observed that the rainy season consistently leads to a significant increase in casting defects, primarily due to porosity in casting. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in our production of chuck bodies, which constitute a large portion of our castings. We use a cupola furnace with specific configurations for melting, achieving an average molten iron temperature of around 1380°C. However, during the rainy season, ambient humidity rises sharply,炉料 become damp, furnace temperature fluctuates, and molten iron temperature drops. This results in a dramatic spike in scrap rates, with porosity in casting being the dominant cause. In peak rainy months, scrap rates can soar to over 30%, with porosity accounting for about 70% of these defects. Even outside the rainy season, porosity in casting remains a contributor, though to a lesser extent. The curve of annual scrap rate averages clearly shows this seasonal correlation, underscoring the critical impact of environmental factors on casting quality.

To effectively combat porosity in casting, it is essential to understand the types and sources of gases involved. During rainy seasons, we primarily encounter three types of porosity: precipitated porosity, oxidation porosity (reaction porosity), and invasive porosity. Precipitated porosity forms when gases dissolved in the molten iron—typically hydrogen (H₂) and nitrogen (N₂)—are released during solidification due to decreased solubility. Oxidation porosity arises from reactions within the molten iron, such as carbon reacting with oxygen to produce CO gas. Invasive porosity results from gases generated by molds or cores, or from air entrapment during pouring. All these are manifestations of porosity in casting caused by H₂, N₂, CO, and other gases. Below, I analyze the sources and characteristics of each gas, focusing on how they contribute to porosity in casting.

Hydrogen is a key culprit in porosity in casting. Its main sources include moisture from humid air, rusted metal charge materials, and damp炉料. During melting, reactions such as the following occur:

$$ \text{H}_2\text{O} \rightarrow \text{H}_2 + \frac{1}{2}\text{O}_2 $$

$$ \text{H}_2\text{O} + \text{C} \rightarrow \text{H}_2 + \text{CO} $$

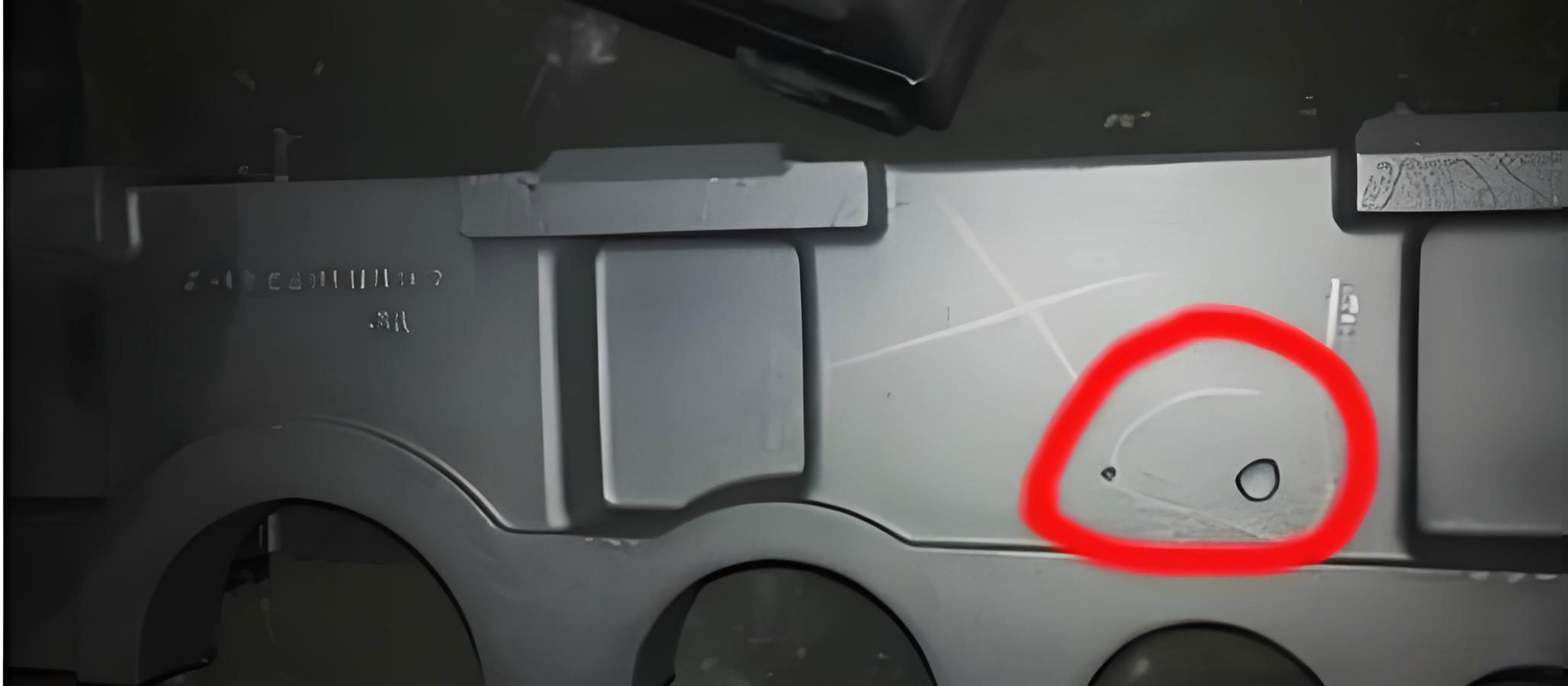

Additionally, when wet air is blasted into the furnace, it contacts hot coke and iron droplets, generating H₂ and CO gases, which increase the hydrogen content in the molten iron. If this hydrogen is not expelled during cooling, it forms hydrogen-induced porosity in casting. Research indicates that the critical hydrogen content for porosity formation is approximately 2.5–3.0 ppm; exceeding this threshold leads to defects. Hydrogen porosity typically appears 1–3 mm beneath the upper surface of castings. Upon machining, the pores are found to be round or oval, with a bright, continuous graphite film inside, and they are often numerous and dispersed. The relationship between blast humidity and hydrogen content in molten iron is crucial, as shown in Table 1.

| Blast Humidity (g/m³) | Hydrogen Content in Molten Iron (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 5 | 1.8 |

| 10 | 2.2 |

| 15 | 2.8 |

| 20 | 3.5 |

Nitrogen is another significant factor in porosity in casting. It primarily originates from the air supplied to the cupola (air contains about 78% N₂), which dissociates into atomic nitrogen at high temperatures and dissolves into the molten iron. Secondary sources include nitrogen in scrap steel and other metal charge materials, as well as nitrogen from molds and cores. In rainy seasons, lower molten iron temperature and poor fluidity hinder nitrogen release. When producing high-strength cast iron with significant scrap steel additions (e.g., 30–50% in the charge), nitrogen pickup increases because scrap steel has low carbon and silicon but higher nitrogen content. The relationship between scrap steel addition and nitrogen content is summarized in Table 2. Generally, porosity in casting due to nitrogen is more prevalent in low-carbon-equivalent irons, such as inoculated cast iron and malleable cast iron. Nitrogen pores are found deep within the casting surface, often irregular in shape, with a less bright interior and discontinuous graphite film.

| Scrap Steel Addition in Charge (%) | Nitrogen Content in Molten Iron (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 40 |

| 30 | 60 |

| 50 | 80 |

| 70 | 100 |

Oxidation porosity, a form of reaction porosity, stems from oxygen sources like air,炉气中的 CO₂ and O₂, rust on metal charge, and sand inclusions. When molten iron is severely oxidized, it contains excess FeO. During solidification at the eutectic temperature, the following reaction occurs:

$$ \text{FeO} + \text{C} \rightarrow \text{Fe} + \text{CO} \uparrow $$

The CO gas accumulates, leading to porosity in casting if not vented. In rainy seasons, high humidity accelerates oxidation and rusting of炉料, while moisture-laden air reduces furnace temperature, slowing reduction reactions and promoting oxidation. This increases FeO content, decarburizes the iron, lowers carbon equivalent, and causes severe silicon and manganese loss, all fostering CO generation. The level of FeO in slag correlates with the total oxygen content in molten iron, serving as an indicator of oxidation severity. Suitable total oxygen content for cast iron is recommended to be below 40 ppm, with lower values preferred. Table 3 shows the relationship between slag FeO and total oxygen content. Controlling slag FeO below 8% is advisable, and in our practice, we aim for around 5%.

| Slag FeO Content (%) | Total Oxygen in Molten Iron (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 5 | 30 |

| 10 | 50 |

| 15 | 80 |

| 20 |

Oxidation pores often appear as spherical or cylindrical holes near the upper casting surface, resembling pinholes. They vary in size, are numerous, have a dark interior with gray or blue walls, and may contain small iron inclusions. When slag accumulates on the casting surface or in dead zones, such porosity in casting is likely after machining.

Controlling porosity in casting requires a multifaceted approach. Based on our experience, the following measures are essential to mitigate porosity in casting, especially during humid conditions.

First, strict control of blast humidity is paramount. Absolute humidity, defined as the water vapor content per cubic meter of air, can reach up to 20 g/m³ during peak rainy months in our region, whereas normal levels are below 10 g/m³. Table 4 illustrates the impact of humidity on the melting process and porosity in casting. It shows that at absolute humidity above 15 g/m³,批量气孔 occur in chuck bodies, while below 10 g/m³, porosity is minimal. International guidelines suggest keeping absolute humidity under 10 g/m³; some recommend 5–8 g/m³. High humidity not only promotes porosity in casting but also affects melting rate, composition, mechanical properties, inoculant efficiency, and chill depth. Dehumidification methods include absorption, adsorption, and freezing, but due to limitations, we often rely on alternatives like hot blast, oxygen-enriched blast, or oxygen injection (especially in the well) to reduce air intake and moisture ingress.

| Absolute Humidity (g/m³) | Relative Humidity (%) | Molten Iron Temperature (°C) | Porosity in Casting Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 45 | 1400 | No porosity |

| 10 | 65 | 1385 | Minor porosity |

| 15 | 80 | 1370 | Significant porosity |

| 20 | 90 | 1355 | Severe batch porosity |

Second, rigorous process control is vital. All炉料—including fuel, metal charge, fluxes, refractory bricks, and wood—must be stored in dry areas, protected from rain. The cupola lining (especially the well and forehearth), ladles, and runners should be thoroughly dried. Inadequate drying during the first 30 minutes of operation can lead to hydrogen porosity, so initial heating must be sufficient. After major repairs, an additional drying cycle is recommended. We avoid or minimize use of炉料 with high gas content. In配料, while meeting mechanical property requirements, we increase carbon and silicon content to reduce hydrogen solubility in molten iron; lower-grade cast irons exhibit less porosity in casting. Special attention is paid to inoculants like ferrosilicon—their particle size, storage, preheating, and addition rate must be managed to prevent batch porosity.

Third, optimizing molten iron temperature is key. Each cast iron grade has an ideal temperature range. Excessive temperature increases gas solubility (e.g., hydrogen and nitrogen) and can cause other defects like cracks, while low temperature impedes gas expulsion, fostering porosity in casting. Given that many foundries struggle with low temperatures (above 1400°C is rare), elevating temperature is crucial. We aim for a balance: high enough to ensure fluidity and degassing, but not so high as to exacerbate gas pickup. The relationship between temperature and gas solubility can be expressed approximately as:

$$ S = k \cdot e^{-\frac{\Delta H}{RT}} $$

where \( S \) is gas solubility, \( k \) is a constant, \( \Delta H \) is enthalpy of solution, \( R \) is the gas constant, and \( T \) is temperature. For hydrogen in iron, solubility decreases with cooling, so proper superheat helps release gases before solidification.

Fourth, ladle degassing treatments are beneficial. To purify molten iron, we add degassing agents in the runner. For nitrogen removal, elements like titanium, boron, zirconium, or magnesium are introduced to form stable nitrides (e.g., TiN, BN), which segregate into slag. The reactions can be represented as:

$$ \text{Ti} + \text{N} \rightarrow \text{TiN} $$

$$ \text{Mg} + \text{N} \rightarrow \text{Mg}_3\text{N}_2 $$

Rare earth silicide alloys are also used for deoxidation and desulfurization, but slag must be skimmed post-treatment to prevent re-entrainment. These practices directly reduce the gas content that causes porosity in casting.

Fifth, mold and core sand requirements cannot be overlooked. We ensure high permeability in molding and core sands by minimizing binders with high gas evolution. Adequate venting holes are poked in molds and cores. The gating system is designed to facilitate escape of entrapped and evolved gases. We prefer hot mold pouring—dry molds are better than green sand molds, and heated dry molds outperform cold ones. However, in humid weather, even hot dry molds should not be stored too long (e.g., over 24 hours) to avoid surface moisture absorption, which can lead to invasive hydrogen porosity. The gas evolution rate from sands can be modeled as:

$$ G(t) = G_0 \cdot e^{-kt} $$

where \( G(t) \) is gas volume at time \( t \), \( G_0 \) is initial gas potential, and \( k \) is a decay constant. Using low-gas sands reduces this source of porosity in casting.

In addition to these measures, we monitor chemical composition closely. Carbon equivalent (CE) plays a role in porosity susceptibility; higher CE generally reduces porosity risk. CE is calculated as:

$$ \text{CE} = \%\text{C} + \frac{1}{3}(\%\text{Si} + \%\text{P}) $$

Maintaining CE above 4.0 for gray cast irons helps minimize porosity in casting. We also track oxygen activity using sensors where possible, as low oxygen activity indicates reduced oxidation potential.

Furthermore, statistical process control aids in predicting porosity in casting. We record humidity, temperature, and composition data to correlate with defect rates. Regression models can help identify thresholds; for instance, a simple linear relation for hydrogen porosity risk might be:

$$ P_{\text{H}} = a \cdot H_{\text{abs}} + b $$

where \( P_{\text{H}} \) is the probability of hydrogen porosity, \( H_{\text{abs}} \) is absolute humidity, and \( a, b \) are coefficients derived from historical data. Such analytics enable proactive adjustments during rainy forecasts.

Another aspect is charge material preparation. We preheat scrap steel and other炉料 to drive off moisture and reduce thermal shock to the furnace. Preheating to 200–300°C can cut humidity-related gas pickup significantly. This is especially critical for materials with high surface area, like turnings, which are prone to rust and moisture retention.

Slag control is integral to managing porosity in casting. Since slag FeO content correlates with oxidation, we use basic slags to suppress FeO formation. The equilibrium between FeO and molten iron can be expressed as:

$$ \text{FeO} \rightleftharpoons \text{Fe} + \text{O} $$

By adding lime (CaO) or other basic fluxes, we shift the equilibrium to reduce oxygen activity. Slag basicity index \( B \) is monitored:

$$ B = \frac{\%\text{CaO}}{\%\text{SiO}_2} $$

Aim for \( B > 1.5 \) to enhance desulfurization and deoxidation, indirectly curbing porosity in casting.

Inoculation practices also affect porosity in casting. Over-inoculation can increase gas nucleation sites, while under-inoculation may lead to undercooling and gas entrapment. We optimize inoculant addition based on temperature and composition, often using late inoculation techniques to minimize gas pickup.

Finally, education and training of personnel ensure consistent application of these measures. We emphasize the importance of humidity awareness and proper handling during rainy seasons. Regular audits of炉料 storage and furnace operations help sustain low porosity in casting levels.

In summary, porosity in casting during rainy seasons is a complex issue driven by increased humidity, which elevates hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen levels in molten iron. Through comprehensive control—managing blast humidity, optimizing工艺, raising temperatures, employing degassing treatments, and improving mold sands—we can significantly reduce porosity in casting. Our experience shows that absolute humidity should be kept below 10 g/m³, slag FeO under 8%, and molten iron temperature sufficiently high for degassing. By integrating these strategies, we have lowered scrap rates from over 30% to below 5% in critical periods, demonstrating that proactive management can mitigate the seasonal challenge of porosity in casting. Continued research into advanced dehumidification and real-time monitoring will further enhance our ability to produce high-quality castings year-round.