In the production of high-integrity aluminum alloy castings for aerospace applications, the occurrence of defects such as shrinkage and gas porosity presents a significant challenge. These defects, collectively and individually detrimental to mechanical properties and pressure tightness, often necessitate costly repairs or lead to component scrap. This article details a comprehensive analysis and resolution of such issues encountered in a specific ZL205A alloy fairing casting, translating the empirical findings into generalized principles and strategies for the foundry engineer. The term porosity in casting will be used throughout to encompass both gas-related and shrinkage-type voids.

1. Case Study: The Fairing Casting

The component in question was a rotational fairing with a maximum contour dimension of Ø400 mm x 400 mm, weighing 28 kg with a total poured weight of 65 kg. Manufactured from ZL205A alloy, a high-strength aluminum-copper alloy, it featured a complex internal cavity with non-uniform wall thickness: predominantly 8 mm with localized sections up to 30 mm thick. The casting was subjected to rigorous inspection standards, including 100% X-ray and fluorescent penetrant testing. The initial low-pressure sand casting process utilized resin-bonded core assemblies with green sand backing.

2. Initial Defects and Root Cause Analysis

The first trial batch revealed three primary defects, providing a clear focal point for metallurgical investigation.

| Defect Location | Defect Type | Root Cause Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| A. Bottom Flange (Near Ingate) | Shrinkage Porosity | Localized superheat from metal impingement; sharp thermal junction due to small fillet radius; poor feeding in final freezing zone. |

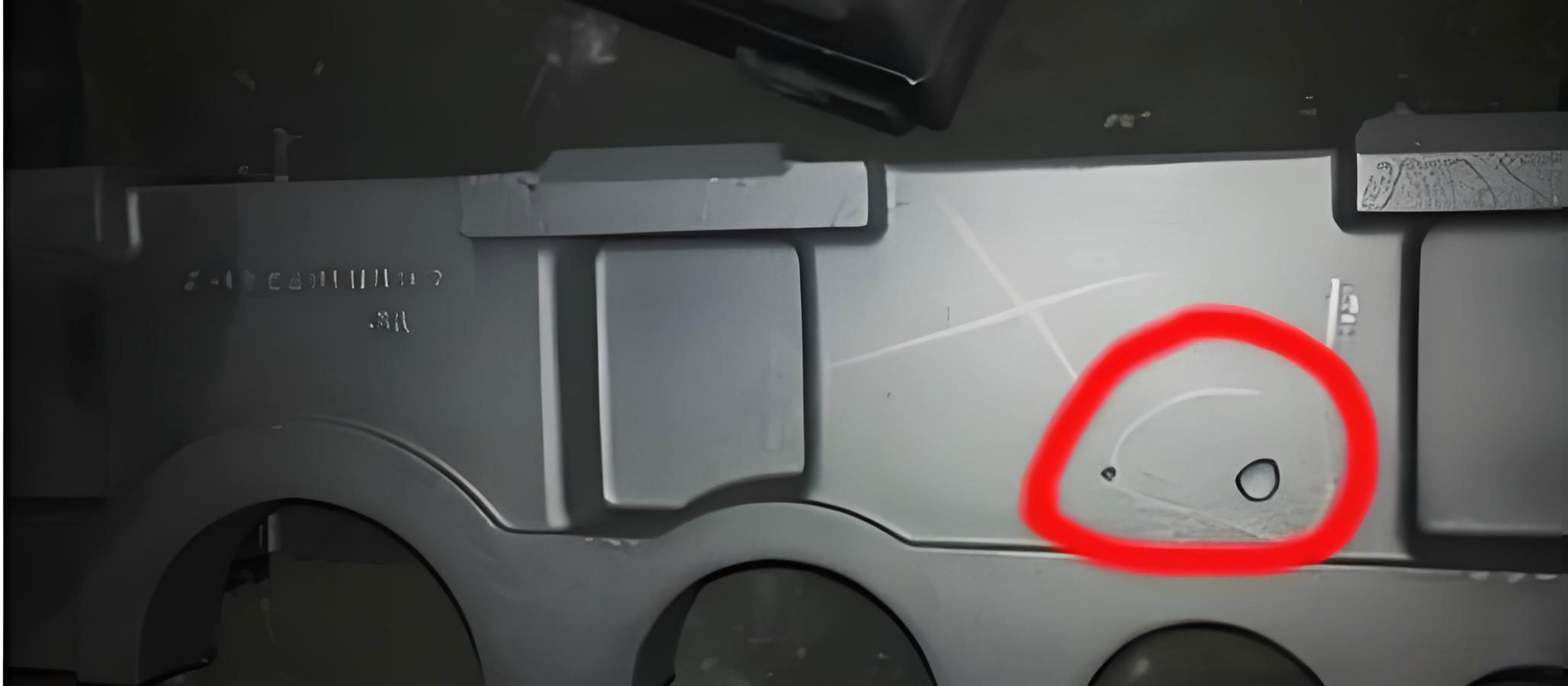

| B. Upper Internal Cavity (Near Core) | Isolated Gas Pores (2-3 mm) | Entrapped air or core gas unable to escape before solidification of thin section. |

| C. Wall Thickness Variation | Dimensional Inaccuracy | Instability of a tall core with only a single lower locator, leading to core shift during filling. |

2.1. The Mechanism of Shrinkage Porosity in Casting

Shrinkage defects are a direct consequence of the volumetric contraction of the alloy during solidification, compounded by inadequate feeding. For alloys like ZL205A, which exhibit a mushy freezing mode, the problem is exacerbated. The solidification sequence can be described in stages:

- Liquid Cooling: The alloy cools from the pouring temperature to the liquidus temperature, $T_L$.

- Mushy Zone Formation: As temperature drops between $T_L$ and the solidus temperature $T_S$, a coherent network of solid dendrites forms. The fraction solid, $f_s$, increases, dramatically impeding interdendritic fluid flow. The permeability, $K$, of the mushy zone can be approximated by the Carman-Kozeny equation:

$$K = \frac{\lambda_2^2 (1 – f_s)^3}{180 f_s^2}$$

where $\lambda_2$ is the secondary dendrite arm spacing. As $f_s$ increases, $K$ decreases rapidly, hindering feeding. - Final Solidification: Isolated liquid pools become trapped within the dendritic network. If these pools are not fed, they result in microporosity in casting.

In Location A, two factors created a severe “hot spot”: continuous metal impingement from the ingate and a sharp geometric junction. This area remained liquid longest, becoming the last point to freeze. With low permeability in the surrounding mushy material, liquid metal could not flow back to compensate for shrinkage, resulting in dispersed porosity in casting.

2.2. The Genesis of Gas Porosity in Casting

The isolated pores found in Location B are classic examples of gas defects. The primary sources of gas leading to porosity in casting are:

| Type | Source | Typical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Entrapped Air | Turbulent filling, vortexing at ingates. | Spherical or elongated bubbles, often in clusters. |

| Core/Gas Invasion | Decomposition of organic binders in cores/molds. | Often larger, spherical pores located near core surfaces. |

| Precipitated Hydrogen | Decrease in hydrogen solubility upon solidification. $S_{solid} \ll S_{liquid}$ | Fine, diffuse microporosity throughout the section. |

For the fairing, the deep, thin-walled cavity formed by the core created a scenario ripe for core gas porosity in casting. As molten metal surrounded the core, the heat caused the resin binder to pyrolyze, generating gas. This gas, under pressure, needed to escape either through the core’s permeable body or via vents. The path to the core print was long and restrictive, and part of the gas was forced to bubble through the already-filled thin section. The local solidification time, $t_f$, for a thin wall is short (approximated by Chvorinov’s rule for a plate: $t_f = B \cdot (V/A)^2$, where B is the mold constant). If the bubble rise velocity, $v$, is too slow to traverse the metal depth, $d$, before $t_f$ elapses ($d/v > t_f$), the bubble is trapped, forming a pore.

3. A Systematic Framework for Defect Elimination

The corrective actions taken for the fairing can be generalized into a three-pronged engineering approach applicable to resolving porosity in casting in complex components.

3.1. Strategy 1: Thermal Management and Feeding Modification

The goal is to control solidification sequence and eliminate isolated hot spots. This involves both modifying the heat input and enhancing heat extraction.

Ingate Redesign: Concentrated metal flow was the primary source of superheat. The solution was to:

- Increase the number of ingates from 5 to 10.

- Reduce individual ingate length to decrease velocity and momentum.

- Distribute ingates around the flange to spread the heat input.

This transforms a single, severe hot spot into multiple, milder thermal points that can be more easily fed from the central riser or feeding gate.

Enhanced Chilling: Strategic use of chills is critical for directional solidification. The effectiveness of a chill is governed by its ability to extract heat, which can be related to the interfacial heat transfer coefficient (HTC) and the chill’s thermal diffusivity, $\alpha = k/(\rho C_p)$. The modifications included:

- Adding contoured chills inside the core (2#) opposite the problem flange to directly extract heat from the hot spot.

- Applying thick (10mm) aluminum facing chills on the outer mold surface (from 5# core) to increase the solidification rate of the thin wall, promoting a more planar front and improving feeding.

The combined effect shifts the thermal center and reduces the size of the pasty zone, minimizing the window for shrinkage porosity in casting.

3.2. Strategy 2: Degassing and Exhaustive Venting for Gas Management

Preventing gas porosity in casting requires a multi-layered defense: minimizing gas generation, preventing its entrapment, and ensuring its escape.

| Target | Method | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Mold/Core Gas | High-permeability core sands, low-gas binders, adequate baking/curing. | Reduces the volumetric rate of gas generation ($\dot{V}_{gas}$). |

| Core Gas Evacuation | Internal venting (e.g., wax/string inserts, perforated cores, hollow core prints). | Provides a low-resistance escape path for gas to the atmosphere, avoiding metal infiltration. |

| Entrapped Air | Passive vents at mold highest points, controlled fill velocity to maintain laminar flow (Reynolds Number, $Re < 2000$). | Allows air displaced by the advancing metal front to exit the cavity. |

| Dissolved Hydrogen | Rotary degassing with inert gas (Ar, N2) prior to pouring. The final hydrogen content should be below a critical threshold, often < 0.10 ml/100g Al for critical castings. | Reduces the hydrogen partial pressure in the melt, minimizing precipitation: $[H]_{solid} = K_H \sqrt{P_{H_2}}$. |

For the fairing, the key interventions were the addition of explicit vent channels from the highest point of the internal cavity and the innovative use of a combustible fiber rope (e.g., jute) embedded within the core. This rope creates a permeable channel that survives core handling but combusts upon metal contact, providing an excellent vent path for core gases directly to the outside, thus preventing invasive gas porosity in casting.

3.3. Strategy 3: Rigorous Dimensional Stability

Core movement is a non-thermal source of defects, leading to wall thinning/thickening and potential leaks in pressure-containing walls. Stability is a function of buoyancy force, core strength, and locator design.

The buoyancy force, $F_b$, attempting to lift or shift the core is:

$$F_b = \rho_{metal} \cdot V_{displaced} \cdot g – \rho_{core} \cdot V_{core} \cdot g$$

Where $V_{displaced}$ is the volume of metal displaced by the core. For a tall, slender core, this creates a significant moment. The initial process relied on a single lower locator. The correction was to add an upper locator (core print), effectively turning the core into a simply supported beam, drastically increasing its resistance to bending moments induced by metallostatic pressure and flow momentum. This is a fundamental principle for preventing dimensional inaccuracies that can indirectly affect feeding and promote local porosity in casting in shifted thin sections.

4. Generalized Principles and Quantitative Relationships

The success of the applied measures can be explained through fundamental solidification and fluid dynamics principles. The Niyama criterion, $G/\sqrt{\dot{T}}$, often used for steel, provides a conceptual framework for predicting shrinkage: a higher thermal gradient ($G$) and a lower cooling rate ($\dot{T}$) favor soundness. Our modifications directly increased $G$ locally via chills. For feeding, Darcy’s law for flow through a porous medium is central:

$$v = -\frac{K}{\mu} \frac{dP}{dx}$$

where $v$ is the feeding velocity, $K$ is the mushy zone permeability (very low for mushy-freezing alloys), $\mu$ is the viscosity, and $dP/dx$ is the pressure gradient. By reducing the length of the mushy zone (increasing $G$) and minimizing the distance $x$ to the feeder, we effectively increase the pressure gradient available for interdendritic feeding, combating porosity in casting.

For gas venting, the principle is to ensure the gas escape velocity exceeds the solidification front advancement velocity. The permeability of a vent channel, combined with the gas generation pressure, must be sufficient to achieve this.

5. Conclusion and Best Practice Guidelines

The resolution of defects in the ZL205A fairing underscores that porosity in casting is rarely the result of a single factor. It is the consequence of a complex interaction between alloy characteristics, geometry, thermal history, and process mechanics. A systematic approach is essential:

- Thermal Analysis First: Employ solidification simulation software to identify hot spots and predict feeding paths. Use chills not just as “problem patches” but as tools to engineer a favorable thermal gradient. For mushy-freezing alloys like ZL205A, this is paramount.

- Aggressive Venting is Non-Negotiable: Never assume core and mold permeability is sufficient. Design explicit, low-resistance vent paths from all enclosed cavities, especially those in thin sections. Consider sacrificial vent materials like rope or wax for deep cores.

- Design for Stability: Treat cores as structural components subjected to significant hydraulic forces. Ensure they are anchored at multiple points to prevent shift, which is a direct cause of scrap.

- Control the Fill: Design gating systems to minimize turbulence and direct impingement. Multiple, smaller ingates are often superior to a few large ones for reducing localized superheat.

The transition from a 100% defect rate in the trial batch to a sustained production yield with minimal gas porosity in casting and eliminated shrinkage validates this integrated methodology. These principles form a robust toolkit for tackling the persistent challenge of porosity in casting across a wide range of complex, high-performance aluminum alloy components.