In my research, I have extensively investigated the influence of multi-stage heat treatment processes on the microstructure and mechanical properties of high chromium white cast iron. White cast iron, particularly the high chromium variant, is renowned for its exceptional wear resistance due to the presence of hard carbides, such as (Cr,Fe)7C3, embedded in a metallic matrix. However, the inherent brittleness and suboptimal toughness of white cast iron often limit its applications under impact conditions. Therefore, optimizing heat treatment to enhance both hardness and toughness is a critical focus in metallurgy. This article delves into my experimental findings, emphasizing how controlled thermal cycles can precipitate secondary carbides and transform retained austenite, thereby improving the overall performance of white cast iron.

The significance of white cast iron in industrial applications cannot be overstated. As a third-generation white cast iron, high chromium white cast iron offers superior abrasion resistance compared to its predecessors, making it ideal for mining, cement production, and machinery components. My work aims to address the trade-off between hardness and toughness by exploring multi-stage heat treatments, which involve holding at elevated temperatures followed by subsequent stages at lower temperatures. Through this approach, I seek to manipulate carbide precipitation and matrix transformation, ultimately achieving a balanced set of properties in white cast iron.

In my experiments, I utilized a high chromium white cast iron with a composition designed for optimal carbide formation. The chemical composition, as determined by spectroscopy, is summarized in Table 1. This white cast iron was melted in a medium-frequency induction furnace and cast into grinding balls, which were then sectioned for heat treatment and testing. The multi-stage heat treatment process varied the first-stage temperature (1100°C, 1150°C, 1200°C) and second-stage temperature (770°C, 830°C, 890°C, 950°C, 1010°C), with specific holding times and cooling methods, as detailed in the methodology section.

| Element | C | Cr | Si | Mn | Ni | V | P | S | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | 2.03 | 18.02 | 0.78 | 0.48 | 1.93 | 0.6 | <0.032 | <0.039 | Bal. |

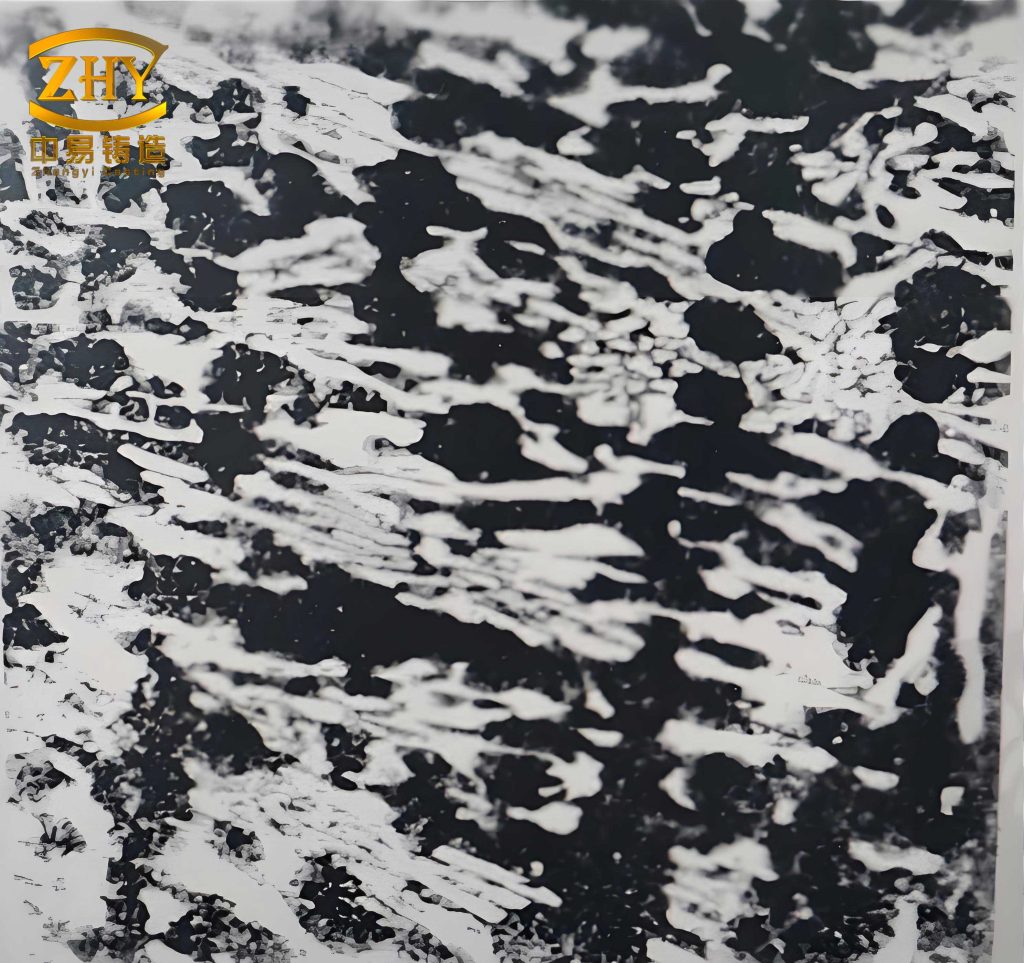

The microstructure of white cast iron plays a pivotal role in determining its mechanical behavior. In the as-cast condition, white cast iron typically consists of primary austenite and eutectic carbides, often forming a network-like structure. However, after multi-stage heat treatment, significant changes occur. I observed that the supersaturated carbon and alloying elements in the matrix precipitate as secondary carbides, while retained austenite transforms into martensite. This transformation is crucial for enhancing hardness without compromising toughness in white cast iron. To illustrate the microstructural evolution, I have included a visual representation below, which highlights the typical morphology of white cast iron after heat treatment.

The precipitation kinetics of secondary carbides in white cast iron can be described using diffusion-based models. For instance, the rate of carbide nucleation and growth depends on temperature and time, following the Arrhenius equation for diffusion coefficient: $$D = D_0 \exp\left(-\frac{Q}{RT}\right)$$ where \(D\) is the diffusion coefficient, \(D_0\) is the pre-exponential factor, \(Q\) is the activation energy, \(R\) is the gas constant, and \(T\) is the absolute temperature. In white cast iron, this governs the precipitation of carbides like (Cr,Fe)23C6 and (Cr,Fe)7C3 during heat treatment. Additionally, the volume fraction of carbides, \(f_v\), influences hardness, as approximated by: $$H = H_m + \alpha \cdot f_v$$ where \(H\) is the overall hardness, \(H_m\) is the matrix hardness, and \(\alpha\) is a constant specific to white cast iron. My data corroborates that increased carbide precipitation elevates hardness, but excessive precipitation may embrittle the material.

To quantify the effects of heat treatment on white cast iron, I conducted hardness, impact toughness, and wear tests. The results are consolidated in Table 2, which compares different multi-stage treatments. The hardness of white cast iron showed a clear dependency on the first-stage temperature, with lower temperatures promoting higher hardness due to enhanced martensite formation. Conversely, impact toughness improved with higher first-stage temperatures, attributed to a more homogeneous carbide distribution and residual austenite retention. Wear resistance, measured as weight loss, peaked at specific second-stage temperatures, indicating an optimal balance between carbide hardening and matrix toughness in white cast iron.

| First-Stage Temperature (°C) | Second-Stage Temperature (°C) | Hardness (HRC) | Impact Toughness (J/cm²) | Wear Loss (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1100 | 890 | 58.2 | 6.5 | 0.12 |

| 1150 | 770 | 55.8 | 7.1 | 0.15 |

| 1150 | 890 | 62.4 | 7.8 | 0.08 |

| 1150 | 1010 | 59.3 | 6.9 | 0.11 |

| 1200 | 890 | 53.7 | 8.2 | 0.14 |

The transformation of secondary carbides in white cast iron during multi-stage heat treatment is a complex process. Initially, at higher temperatures, metastable (Cr,Fe)23C6 carbides precipitate due to their good lattice matching with austenite. As holding time increases at lower second-stage temperatures, these carbides undergo in-situ transformation to more stable phases like (Cr,Fe)7C3 and (Cr,V)2C. This transformation can be modeled using phase transformation kinetics, such as the Johnson-Mehl-Avrami-Kolmogorov (JMAK) equation: $$f = 1 – \exp(-k t^n)$$ where \(f\) is the transformed fraction, \(k\) is the rate constant, \(t\) is time, and \(n\) is the Avrami exponent. For white cast iron, this applies to both carbide precipitation and austenite-to-martensite transformation. The presence of vanadium in this white cast iron further promotes the formation of hard (Cr,V)2C carbides, contributing to wear resistance.

My analysis of wear mechanisms in white cast iron reveals that the interplay between carbides and matrix dictates performance. Under abrasive conditions, hard carbides resist penetration, but if the matrix is too soft, carbides can be plucked out, accelerating wear. The optimal heat treatment, such as 1150°C × 2 h + 890°C × 5 h, yields a microstructure with fine, dispersed carbides in a tough martensitic matrix, minimizing weight loss. This aligns with the Archard wear equation, modified for white cast iron: $$W = K \cdot \frac{L}{H}$$ where \(W\) is wear volume, \(K\) is a wear coefficient, \(L\) is load, and \(H\) is hardness. However, in white cast iron, toughness also affects \(K\), as cracks propagate along carbide-matrix interfaces. Thus, improving toughness through heat treatment reduces \(K\), enhancing wear resistance.

The role of residual austenite in white cast iron cannot be overlooked. After heat treatment, some austenite remains, which can transform under stress, providing toughening via transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP). The martensite start temperature, \(M_s\), is critical and can be estimated for white cast iron using empirical formulas based on composition: $$M_s (°C) = 539 – 423C – 30.4Mn – 17.7Ni – 12.1Cr – 7.5Mo$$ where element symbols represent weight percentages. In my white cast iron, the precipitation of carbides during heat treatment lowers carbon and chromium in austenite, raising \(M_s\) and promoting martensite formation. This dynamic stabilizes the matrix, contributing to both hardness and impact resistance in white cast iron.

To further elucidate the effects, I performed statistical analysis on the data, correlating heat treatment parameters with properties. For white cast iron, the relationship between hardness (\(H\)) and first-stage temperature (\(T_1\)) can be approximated linearly: $$H = \beta_0 + \beta_1 T_1 + \epsilon$$ where \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) are coefficients, and \(\epsilon\) is error. Similarly, impact toughness (\(IT\)) relates to second-stage temperature (\(T_2\)): $$IT = \gamma_0 + \gamma_1 T_2 + \delta$$ These models help optimize heat treatment for specific applications of white cast iron. For instance, in high-impact environments, a higher \(T_1\) may be preferred to boost toughness, whereas for pure abrasion, lower \(T_1\) enhances hardness.

In conclusion, my research demonstrates that multi-stage heat treatment is a powerful tool for tailoring the properties of high chromium white cast iron. By controlling temperature and time, I can induce secondary carbide precipitation and matrix transformation, achieving a synergistic improvement in hardness, toughness, and wear resistance. The optimal process identified—1150°C for 2 hours followed by 890°C for 5 hours—results in a white cast iron with superior performance, making it suitable for demanding industrial applications. Future work could explore additive manufacturing of white cast iron or alloy modifications to further enhance properties. Ultimately, understanding these thermal processes allows for the continued advancement of white cast iron as a durable and versatile material.

The implications of this study extend beyond laboratory settings. In practice, heat treatment cycles for white cast iron can be integrated into production lines to produce components like mill liners, grinding balls, and crusher parts with extended service life. By leveraging the insights from carbide precipitation kinetics and transformation behavior, engineers can design white cast iron alloys that resist failure under complex loading conditions. Moreover, the environmental benefits of longer-lasting white cast iron parts contribute to sustainability by reducing material waste and energy consumption in mining and processing industries.

Throughout this article, I have emphasized the importance of white cast iron in modern engineering. The repeated mention of white cast iron underscores its centrality to this discussion. From microstructure to mechanical properties, every aspect hinges on the unique characteristics of white cast iron. As I continue to investigate, I aim to develop predictive models that can simulate heat treatment outcomes for white cast iron, facilitating smarter material design. For now, the experimental evidence solidifies the value of multi-stage heat treatments in unlocking the full potential of white cast iron.

In summary, the journey of optimizing white cast iron through heat treatment is both challenging and rewarding. By delving into the nuances of carbide formation and matrix evolution, I have uncovered pathways to enhance this venerable material. Whether in historic contexts or cutting-edge applications, white cast iron remains a cornerstone of wear-resistant alloys, and with continued research, its future looks even brighter. I hope this comprehensive analysis inspires further exploration into the fascinating world of white cast iron and its thermal processing.