In the automotive industry, the crankshaft is a critical component of internal combustion engines, responsible for converting linear piston motion into rotational torque. Its performance directly impacts engine efficiency, durability, and overall vehicle reliability. Crankshafts operate under severe conditions, including high temperatures, pressures, and cyclic loads from bending, torsion, vibration, and impact. These stresses often lead to fatigue cracks and, ultimately, fracture, posing significant safety risks and economic losses. Therefore, understanding failure mechanisms is essential for improving design, material selection, and manufacturing processes. This article presents a comprehensive failure analysis of a crankshaft made from QT700-2 spheroidal graphite iron, which fractured during road testing. We employ various analytical techniques to identify the root cause and propose mitigation strategies. Throughout this discussion, we emphasize the properties and behavior of spheroidal graphite iron, a material widely used in heavy-duty applications due to its high strength, wear resistance, and fatigue performance.

The failed crankshaft was sourced from a production batch of a specific engine model. The material, QT700-2 spheroidal graphite iron, is characterized by its graphite nodules dispersed in a ferritic-pearlitic matrix, offering a balance of strength and ductility. The fracture occurred at the fourth connecting rod journal, prompting a detailed investigation. We adopted a multi-faceted approach, including macroscopic and microscopic examination, metallographic analysis, chemical composition testing, surface residual stress measurement, and mechanical property evaluation. Our goal is to correlate material characteristics with failure modes, providing insights for enhancing crankshaft longevity.

Macroscopic observation revealed that the fracture initiated at the rolled fillet edge of the fourth connecting rod journal. The crack propagation exhibited a radial pattern, typical of fatigue under torsional loading. The fracture surface showed multiple initiation sites, indicating stress concentration at the fillet region. No obvious impact damage or mechanical wear was detected near the fracture zone. Microscopic analysis using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) further elucidated the fracture morphology. The crack origin displayed quasi-cleavage features, with no evidence of casting defects such as inclusions or porosity. The propagation zone exhibited classic fatigue striations, confirming fatigue as the failure mechanism. The fillet surface appeared smooth without visible machining marks at the bottom, but circumferential machining traces persisted near the edges, suggesting potential stress risers.

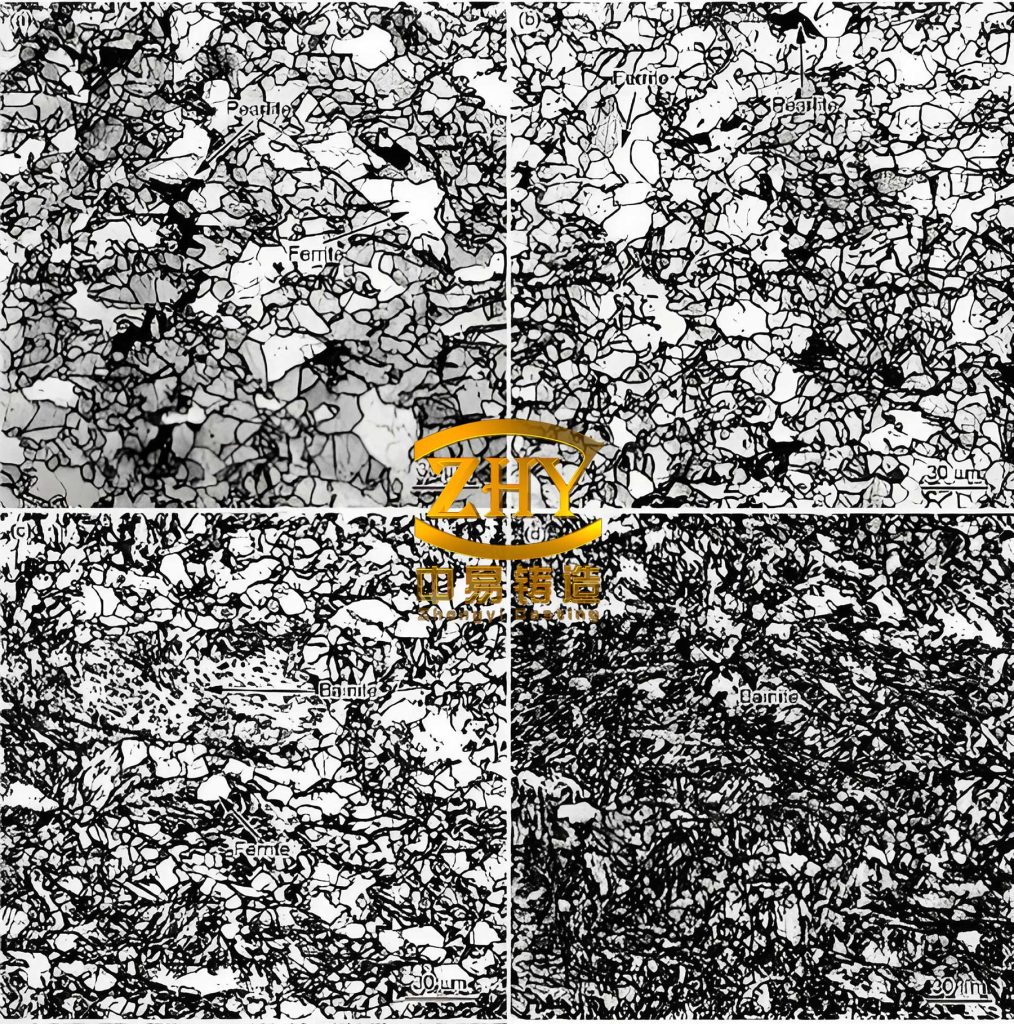

Metallographic examination was conducted on samples from both the fractured fourth journal and an intact first journal for comparison. The graphite morphology was assessed according to standard classifications. Results indicated a spheroidization grade of 1 (≥90% nodularity) and graphite size of 6 (3–6 mm at 100× magnification), consistent with high-quality spheroidal graphite iron. The microstructure comprised ferrite and pearlite, with pearlite content exceeding 98%. Minor amounts of carbides and phosphide eutectic were present, but within acceptable limits. Notably, the quenched layer depth and width varied between journals, indicating inhomogeneity in heat treatment. For instance, the fourth journal had an unquenched zone width of 5.5 mm and 4.5 mm on either side, with a quench depth ranging from 1.5 mm to 2.0 mm. Similarly, the first journal showed asymmetrical quenching. Such inconsistencies can lead to localized stress concentrations and reduced fatigue resistance.

Chemical composition analysis was performed using spectroscopy. The results, compared to standard specifications for QT700-2 spheroidal graphite iron, are summarized in Table 1. Carbon content was slightly below the specified range, which may affect graphite formation and mechanical properties. However, since carbon in spheroidal graphite iron primarily exists as graphite, measurement discrepancies can occur. Other elements like silicon, manganese, sulfur, and phosphorus were within limits, suggesting adequate alloying and impurity control.

| Element | Standard Range | Measured Value |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | 3.60–3.85 | 3.24 |

| Silicon (Si) | 1.90–2.60 | 2.37 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.20–0.70 | 0.40 |

| Sulfur (S) | ≤0.030 | 0.0071 |

| Phosphorus (P) | ≤0.05 | 0.026 |

Surface residual stress is a critical factor influencing fatigue life, as compressive stresses can inhibit crack initiation and propagation. We measured residual stresses at three fillet locations using X-ray diffraction. The stress values, presented in Table 2, revealed compressive stresses at all sites, with the highest magnitude at the first journal fillet. The fractured fourth journal fillet showed lower compressive stress, possibly due to stress relaxation post-fracture. The variation underscores the importance of uniform residual stress distribution in spheroidal graphite iron components.

| Measurement Location | Residual Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|

| First Connecting Rod Journal Fillet (A) | -407.6 ± 22.8 |

| Fourth Connecting Rod Journal Fillet (B) | -333.8 ± 24.7 |

| Fourth Connecting Rod Journal Fillet (C) | -63.3 ± 8.5 |

Mechanical properties were evaluated through hardness testing and tensile tests. Hardness measurements, shown in Table 3, indicated that both core and surface hardness met technical requirements. The surface hardness, influenced by quenching, was consistently high, while core hardness reflected the base material strength. Tensile tests yielded strength and ductility values (Table 4) that exceeded minimum specifications, confirming the adequacy of the spheroidal graphite iron grade. However, property uniformity across the crankshaft is crucial for fatigue performance.

| Location | Core Hardness (HB) | Surface Hardness (HRC) | Technical Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fourth Journal | 268, 270, 275 | 56.0, 55.5, 55.5 | Core: 240–320 HB; Surface: 45–60 HRC |

| First Journal | 291, 280, 280 | 55.5, 55.5, 54.5 | Core: 240–320 HB; Surface: 45–60 HRC |

| Sample | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 970 | 589 | 7.5 |

| 2 | 999 | 617 | 8.0 |

| Requirement | ≥770 | ≥480 | ≥3 |

To understand the fatigue failure mechanism, we consider the stress state at the fillet region. Crankshafts experience complex loading, primarily torsional and bending moments. The stress concentration factor (Kt) at fillets can be approximated using empirical formulas. For a rounded notch, the stress concentration under torsion is given by:

$$ K_t = 1 + \sqrt{\frac{r}{d}} \cdot f\left(\frac{D}{d}\right) $$

where r is the fillet radius, d is the journal diameter, D is the adjacent shaft diameter, and f is a geometry-dependent function. In this case, the fillet radius and machining quality directly influence Kt. The presence of circumferential marks near the edges likely elevated Kt, promoting crack initiation. Additionally, the fatigue life of spheroidal graphite iron can be modeled using the Basquin equation:

$$ \sigma_a = \sigma_f’ (2N_f)^b $$

where σa is the stress amplitude, σf’ is the fatigue strength coefficient, Nf is the number of cycles to failure, and b is the fatigue strength exponent. For spheroidal graphite iron, microstructural homogeneity and residual stresses significantly alter these parameters. The observed quench layer variation implies non-uniform fatigue strength across the crankshaft, reducing life in weaker regions.

The role of residual stress in fatigue is paramount. Compressive residual stresses, often introduced by processes like rolling or shot peening, can enhance fatigue limit by reducing the mean stress. The effective stress amplitude (σeff) considering residual stress (σr) is:

$$ \sigma_{\text{eff}} = \sigma_a + \sigma_m – \sigma_r $$

where σm is the mean stress. For compressive σr, σeff decreases, extending fatigue life. Our measurements show that the fractured fillet had lower compressive stress, potentially increasing σeff and accelerating crack growth. This highlights the need for optimized surface treatments in spheroidal graphite iron crankshafts.

Microstructural analysis further supports the failure cause. The spheroidal graphite iron exhibited a pearlitic matrix with high hardness, which is beneficial for wear resistance but may reduce toughness. Fatigue cracks in such materials often initiate at graphite-matrix interfaces or microporosities. However, our examination revealed no significant defects at the crack origin, suggesting that stress concentration and loading conditions were primary drivers. The quasi-cleavage mode indicates brittle fracture under cyclic loading, typical of high-strength spheroidal graphite iron under torsional stresses.

In discussing the failure, we must consider manufacturing processes. The crankshaft undergoes machining, heat treatment, and surface rolling. Inhomogeneous quenching, as detected, can create soft zones that act as stress concentrators. Moreover, the rolling process may not have uniformly imparted compressive stresses, leaving some areas vulnerable. The smooth fillet bottom without visible deformation suggests inadequate rolling penetration, which could compromise fatigue resistance. For spheroidal graphite iron, precise control of these processes is essential to ensure consistent properties.

To mitigate such failures, we propose several improvements. First, optimize heat treatment to achieve uniform quench depth and microstructure across all journals. This may involve adjusting heating rates, quenching media, or tempering parameters. Second, enhance machining practices to eliminate stress risers, particularly at fillet edges. Precision grinding or polishing can reduce surface roughness and improve fatigue strength. Third, implement advanced surface strengthening techniques, such as severe shot peening or laser shock peening, to induce deep compressive residual stresses. These methods can significantly boost the fatigue limit of spheroidal graphite iron components.

Additionally, material selection and design modifications could be explored. While QT700-2 spheroidal graphite iron offers excellent properties, higher-grade alloys with improved toughness might be considered for extreme applications. Design-wise, increasing fillet radii or using gradual transitions can lower stress concentration factors. Finite element analysis (FEA) can simulate stress distributions under operational loads, guiding design optimizations. Regular non-destructive testing (NDT) during production can also detect early defects, preventing faulty components from entering service.

In conclusion, the crankshaft failure resulted from multi-site fatigue crack initiation at the fourth connecting rod journal fillet, driven by torsional cyclic loading and stress concentration. Material analysis confirmed that the spheroidal graphite iron met most specifications, but process-induced inhomogeneities in quenching and residual stress distribution contributed to the failure. By addressing these issues through improved heat treatment, machining, and surface engineering, the fatigue life of spheroidal graphite iron crankshafts can be substantially enhanced. This case underscores the importance of holistic quality control in manufacturing critical automotive components.

Future work should focus on developing predictive models for fatigue life in spheroidal graphite iron, incorporating microstructural and residual stress data. Accelerated testing protocols could validate process improvements. Collaboration between material scientists and engineers will drive innovations in spheroidal graphite iron applications, ensuring reliability and performance in demanding environments. As the automotive industry evolves towards higher efficiency and durability, understanding and optimizing materials like spheroidal graphite iron will remain paramount.