As a practitioner in the field of metal casting, I have extensively worked with lost foam casting processes, which have revolutionized the production of complex and high-precision machine tool castings. This method, originally developed and patented in the mid-20th century, offers significant technical and economic advantages, driving advancements in casting technology. However, it is not without challenges, particularly when applied to large-scale machine tool castings like upright columns and similar components. In this article, I will share my experiences and insights into addressing common defects such as penetration, collapse, and iron nodules in machine tool castings, using data-driven approaches including tables and mathematical models to optimize the process.

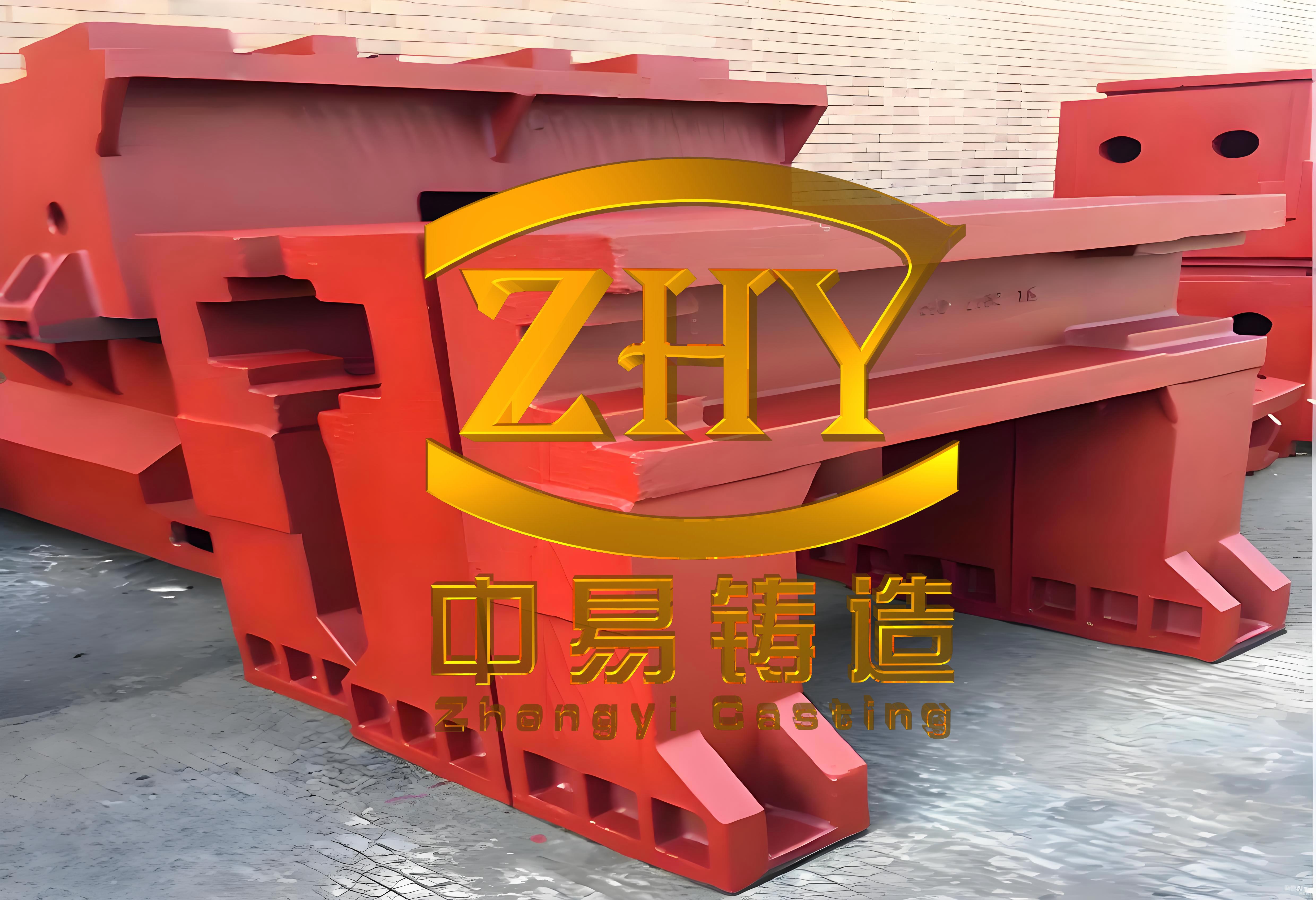

The lost foam casting process involves creating a foam pattern that is embedded in sand and then replaced by molten metal, resulting in precise machine tool castings. Over the years, I have focused on enhancing the quality of machine tool castings, especially for structural components like upright columns, which demand dimensional accuracy within tight tolerances. For instance, in one project, we produced double-wall upright columns with dimensions up to 1400 mm in length and 800 kg in weight, where initial rejection rates exceeded 80% due to dimensional inaccuracies. By refining process parameters, we achieved remarkable improvements, underscoring the importance of systematic optimization in machine tool castings.

One of the primary defects encountered in machine tool castings is penetration, where sections of the casting fail to form properly, leading to incomplete shapes. This often occurs in areas with large internal cavities and limited venting pathways. During pouring, the foam decomposes rapidly, generating gases that must be evacuated quickly. If the negative pressure is insufficient, the sand mold’s rigidity cannot withstand the buoyant force of the molten metal, causing sand displacement and mold failure. The buoyant force can be modeled using the equation: $$F_b = \rho_m g V_d$$ where \(F_b\) is the buoyant force, \(\rho_m\) is the density of the molten metal, \(g\) is gravitational acceleration, and \(V_d\) is the displaced volume. In machine tool castings, optimizing the gating system to avoid direct impingement on internal cavities is crucial to mitigate this issue.

Another common defect in machine tool castings is collapse, where the top sections of the casting exhibit missing material or incomplete formation. This is frequently due to inadequate sand coverage and low negative pressure levels. For large machine tool castings, the top sand cover must be sufficient to resist the metal’s buoyancy. Based on my experiments, a minimum sand cover of 150 mm is essential to prevent collapse. The relationship between negative pressure and mold stability can be expressed as: $$P_{neg} \geq \frac{F_b}{A_s}$$ where \(P_{neg}\) is the negative pressure, \(F_b\) is the buoyant force, and \(A_s\) is the cross-sectional area of the sand mold. By maintaining a negative pressure range of 0.038 to 0.045 MPa, we have successfully eliminated collapse in machine tool castings.

Iron nodules, or surface protrusions, are another defect that plagues machine tool castings. These result from inadequate sand compaction during vibration, leading to gaps that allow molten metal to penetrate the coating. To address this, we refined the vibration parameters to ensure uniform sand density. The table below summarizes the optimized vibration parameters that have proven effective for machine tool castings, based on multiple trials:

| Filling Speed | Vibration Mode | Zone Time (s) | Sand Height (mm) | Motor Speed (rpm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast | Initial | 20 | 0 | 3600 |

| Fast | Initial | 20 | 200 | 2600 |

| Slow | Vertical | 30 | 150 | 2800 |

| Slow | Upward | 20 | 0 | 2800 |

| Slow | Downward | 20 | 0 | 3000 |

| Slow | Vertical | 20 | 200 | 3000 |

| Slow | Horizontal | 30 | 150 | 3000 |

| Slow | Downward | 20 | 100 | 3000 |

| Slow | Upward | 20 | 100 | 3600 |

| Fast | Vertical | 20 | 100 | 3600 |

In addition to vibration control, the design of the gating system plays a pivotal role in producing high-quality machine tool castings. We adopted a multi-point gating approach to distribute molten metal evenly and avoid direct冲击 on internal sand cores. The gating ratio, which influences flow dynamics, can be calculated using: $$Q = A_g \cdot v$$ where \(Q\) is the flow rate, \(A_g\) is the cross-sectional area of the gate, and \(v\) is the flow velocity. For machine tool castings, smaller gates are preferred to reduce turbulence and gas entrapment. Furthermore, negative pressure during pouring must be carefully regulated; our studies show that a range of 0.038–0.045 MPa ensures mold integrity without causing excessive gas evolution.

To quantify the improvements, we conducted a series of experiments on machine tool castings, measuring defect rates before and after parameter adjustments. The following table compares the initial and optimized process conditions for typical machine tool castings, highlighting the reduction in defects:

| Parameter | Initial Value | Optimized Value | Impact on Defects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top Sand Cover (mm) | 100 | 150 | Eliminated collapse |

| Negative Pressure (MPa) | 0.030–0.035 | 0.038–0.045 | Reduced penetration |

| Gating Design | Single-point | Multi-point | Improved filling |

| Vibration Time (s) | Variable | Staged as per table | Minimized iron nodules |

Through these optimizations, we consistently produced machine tool castings with no visible defects, achieving dimensional accuracies within ±2 mm. The success underscores the importance of an integrated approach, combining gating design, vibration parameters, and negative pressure control. For instance, in one batch of double-wall upright columns—a common machine tool casting—we achieved a 100% success rate after implementing these changes, demonstrating the scalability of the method for various machine tool castings.

Moreover, the economic benefits of optimizing lost foam casting for machine tool castings are substantial. By reducing rejection rates, we lower production costs and enhance sustainability. The total cost savings can be estimated using: $$C_{savings} = (R_{initial} – R_{optimized}) \times C_{unit}$$ where \(C_{savings}\) is the cost savings, \(R_{initial}\) and \(R_{optimized}\) are the initial and optimized rejection rates, and \(C_{unit}\) is the cost per unit of machine tool castings. In our case, this translated to significant financial gains, making the process more competitive for high-precision applications.

In conclusion, the lost foam casting process is highly effective for producing complex machine tool castings, but it requires meticulous parameter control. Key takeaways from my experience include: employing multi-point gating to avoid direct metal flow onto sand cores; ensuring a minimum top sand cover of 150 mm for large machine tool castings; using staged vibration parameters to achieve uniform sand compaction; and maintaining an optimal negative pressure range to prevent mold failure. These strategies have proven reliable across multiple projects, resulting in superior machine tool castings that meet stringent industry standards. As the demand for precision components grows, continued refinement of these techniques will further advance the field of machine tool castings, driving innovation in manufacturing.