The transition towards electrification in the commercial vehicle sector demands powertrain components with exceptional strength, reliability, and the capacity to manage significantly higher instantaneous torque. Our company’s renowned dual-intermediate-shaft transmission design provides a robust foundation. To meet the escalating requirements for high torque, substantial power, and unwavering stability in applications like electric vehicles and mining trucks, we embarked on the development of a next-generation three-intermediate-shaft electric transmission. The successful production of its defining component, the housing, presented a formidable casting challenge.

The inherent complexity of these transmission shell castings, characterized by thin walls and semi-enclosed internal cavities, makes them ideally suited for the lost foam casting process. This advanced method, also known as full mold casting, involves placing a foam pattern coated with refractory material into dry sand to form the mold. The sand is compacted via vibration, and a vacuum is applied throughout pouring and solidification. This crucial vacuum ensures gases from the vaporizing and burning foam are efficiently evacuated through the coating, simultaneously increasing mold rigidity and cooling rate, allowing molten metal to precisely replicate the pattern’s shape.

When producing gray iron castings via lost foam, particular attention must be paid to material selection and solidification mechanics. Typically, hypo-eutectic or near-eutectic gray iron is used, each with distinct solidification behaviors. Hypo-eutectic gray iron exhibits an intermediate freezing mode, while eutectic gray iron tends towards skin-forming solidification. A critical advantage of gray iron is the expansion associated with graphite precipitation during solidification, which can compensate for a portion of the volumetric shrinkage. Therefore, the design of the feeding system primarily focuses on supplying liquid metal to compensate for the initial liquid contraction.

Structural Challenges of the Housing Shell Casting

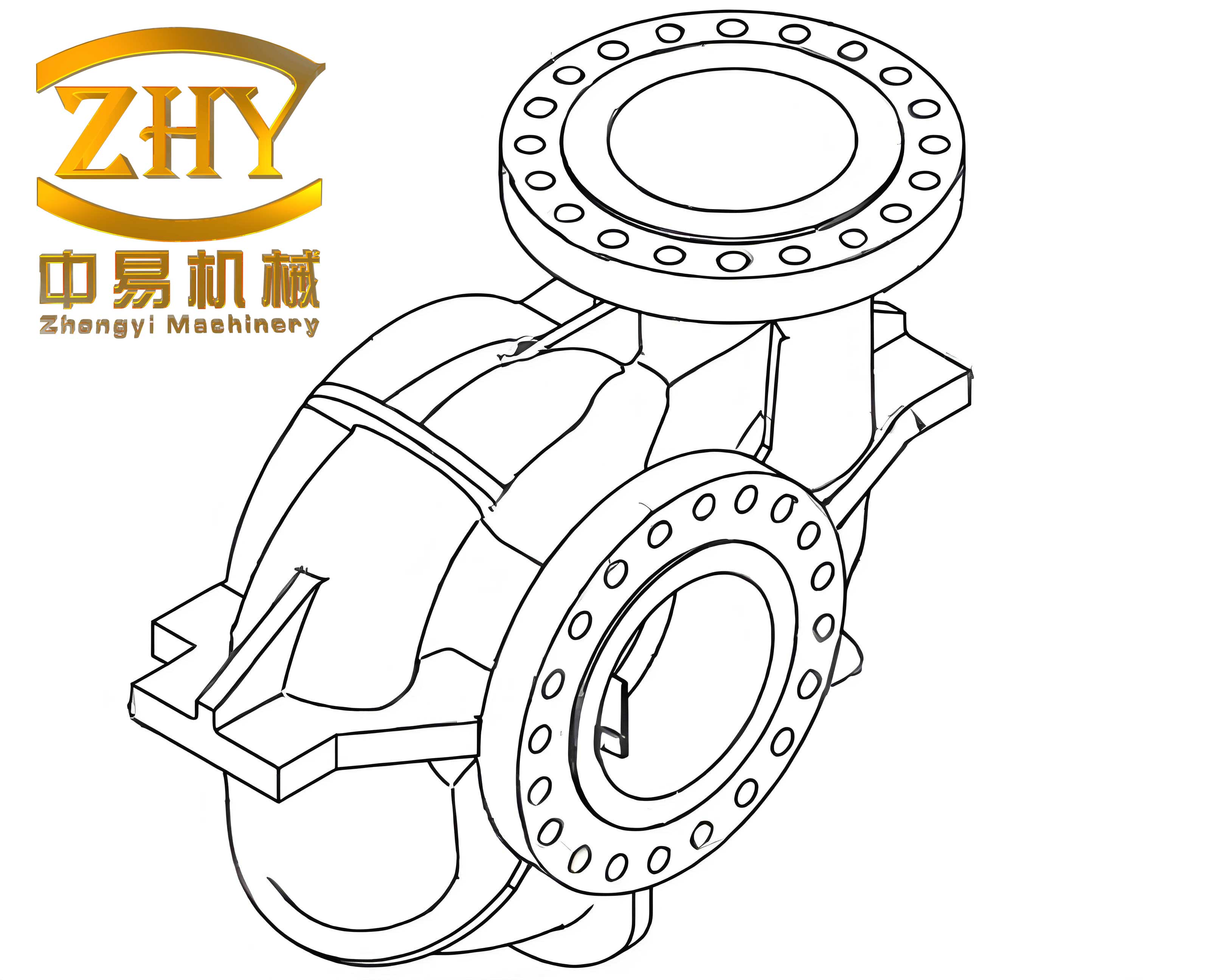

As a core component of a commercial vehicle transmission, this housing serves multiple critical functions: it supports and locates the entire gear train, contains and manages lubricating oil, and provides a secure mounting interface to the vehicle chassis. The three-intermediate-shaft configuration results in a complex geometry for the shell castings. The part weighs approximately 75 kg, is made of HT250 gray iron, and has overall dimensions of 544 mm x 518 mm x 552 mm. Its main wall thickness is 8 mm, with reinforcing ribs of 10 mm. However, a significant feature is the 21 mm thick front face, which houses the bearing seats for the shafts. The total volume of the casting is substantial, at approximately 11,464,230 mm³. This front face represents a major geometric and thermal challenge.

The quality standards for these transmission shell castings are stringent. The material must conform to HT250 specifications. Internally, shrinkage porosity and cavities are unacceptable. Surface defects such as cracks and slag inclusions are also prohibited. Dimensional accuracy is critical, with tight tolerances on both machined and as-cast features. Ensuring these standards are met is paramount for the durability and performance of the final transmission unit.

Analysis of the Casting Defect Mechanism

The primary challenge in producing these shell castings stems from the combination of geometric and thermal factors at the thick front face. This area acts as a significant heat sink, or thermal mass, during solidification. In lost foam casting, the pouring process itself can exacerbate this issue. The sustained flow of hot metal directly onto a specific area of the mold, known as flow-induced heating, can create a severe thermal concentration, or “hot spot.” When this flow-induced hot spot coincides with a pre-existing geometric hot spot (the thick section), the result is a superposed thermal center that solidifies last and is most prone to shrinkage defects.

Mathematically, the solidification time for a section can be approximated using Chvorinov’s rule:

$$ t = B \left( \frac{V}{A} \right)^n $$

where \( t \) is solidification time, \( V \) is volume, \( A \) is surface area, \( n \) is a constant (often ~2), and \( B \) is a mold constant. For the front face of our shell castings, the high \( V/A \) ratio (modulus) predicts a long local solidification time relative to the thinner walls. The superposition of flow heat further increases the effective local temperature, delaying solidification even more and isolating this region as a liquid “island” after the surrounding sections have frozen, cutting off any potential feed metal path.

Initial Process Design and Numerical Simulation

The base material for the shell castings was a low-alloy synthetic gray iron, HT250, with the target composition shown in Table 1.

| Element | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Ni | Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | 3.1-3.5 | 1.5-2.3 | 0.3-0.85 | ≤0.10 | ≤0.10 | 0.20-0.35 | 0.15-0.30 | 0.05-0.12 |

Leveraging experience from dual-shaft housing production, the initial gating design was a side-bottom fed system. The casting was oriented with the thick front face facing downward. Two ingates with a total cross-sectional area of 1120 mm² were placed at the bottom of this front face, fed by a horizontal runner designed to trap slag (1050 mm²), connected to a downsprue of 41 mm diameter. To address the anticipated hot spot, internal cooling fins (chills) were incorporated into the foam pattern within the cavity opposite the front face. The runner was positioned higher than the ingates to facilitate slag collection during the foamy metal front progression in the lost foam process.

Solidification simulation was performed using MAGMA software under the following key process parameters: Pouring Temperature = 1500°C, Silica Sand mold at 50°C, vacuum applied. The simulation focused on the solidification phase. The results were revealing. The liquid fraction distribution over time clearly showed the formation of an isolated liquid pool at the front face hot spot. While the cooling fins provided some chilling effect, it was insufficient to overcome the combined geometric and flow-induced heating. The simulation predicted a high risk of shrinkage porosity in this critical zone, as the feeding path from the ingates solidified before the hot spot itself, leaving it unfed. The sequence can be described by tracking the liquid fraction \( f_L \) over time \( t \). The critical moment occurs when the feeding path solidifies (\( f_{L,path} \to 0 \)) while the hot spot remains liquid (\( f_{L,hotspot} > 0 \)), leading to pore formation.

Production Validation of the Initial Design

Initial production trials confirmed the simulation’s accuracy. After pouring and cooling, the transmission shell castings were inspected. Non-destructive testing and subsequent machining of the front face revealed significant shrinkage cavities exactly in the predicted location. This defect was unacceptable for the pressure integrity and bearing seat strength of the final component. The root cause analysis aligned with the simulation: the cooling fins were ineffective because (1) the superposed hot spot was too severe, (2) the prolonged metal impingement during pouring overheated the local sand, diminishing the chill effect, and (3) the internal fins partially obstructed vacuum airflow, further reducing heat extraction efficiency. A clear redesign was necessary.

| Process Stage | Observation/Defect | Root Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical Simulation | Predicted isolated liquid pool at front face. | Superposed geometric & flow-induced hot spot. |

| Production Trial | Macro-shrinkage cavities on machined front face. | Premature freezing of ingates, isolating hot spot from feed metal. |

| Conclusion | Process not capable for quality shell castings. | Inadequate feeding & insufficient cooling for the thermal mass. |

Optimized Process: The “Feeder-Runner” Concept

To solve this fundamental feeding problem, we conceptualized and implemented a “feeder-runner” or “gating-as-feeding” strategy. The core idea was to transform a section of the gating system itself into a thermal reservoir that would remain liquid longer than the casting hot spot, thereby providing effective pressure feed until the very end of solidification. The principle relies on ensuring the modulus ( \( M_{runner} \) ) of the feeding runner section is greater than the modulus ( \( M_{hotspot} \) ) of the casting hot spot:

$$ M_{runner} = \frac{V_{runner}}{A_{runner}} > M_{hotspot} = \frac{V_{hotspot}}{A_{hotspot}} $$

If this condition is met, the runner solidifies last and can feed the shrinkage.

The implementation involved a complete redesign. The casting orientation was changed. Crucially, the ingates were now strategically attached directly to the center of the problematic front face hot spot. The runner system was dramatically enlarged in cross-section, effectively turning it into a large, elongated feeder. Specific dimensions were: Ingate cross-section = 420 mm², Primary Runner cross-section = 3650 mm², Downsprue unchanged. Furthermore, to prevent pattern deformation during sand filling due to the heavy cluster, reinforcement using glass fiber rods was incorporated into the foam assembly. This robust “feeder-runner” was designed to act as a heat source rather than a sink, maintaining a liquid connection to the hot spot throughout most of the solidification.

Simulation and Production Validation of the Optimized Design

The optimized design was subjected to the same rigorous MAGMA simulation. The results demonstrated a dramatic improvement. The liquid fraction analysis showed that the large feeder-runner now acted as the last-to-freeze region. The thermal center of the entire system (casting + gating) shifted to this runner. The front face of the shell castings solidified progressively, fed by the liquid metal in the runner, eliminating the isolated liquid pool. The solidification sequence became directional, moving from the thin walls of the casting towards the ingates and finally into the feeder-runner. The criterion for soundness, where the thermal gradient \( \nabla T \) directs solidification towards the feeder, was satisfied:

$$ \nabla T \cdot \hat{r}_{feeder} > 0 $$

where \( \hat{r}_{feeder} \) is the unit vector pointing from the hot spot towards the feeder-runner.

| Parameter | Initial Side-Bottom Feed Process | Optimized “Feeder-Runner” Process |

|---|---|---|

| Casting Orientation | Front face down. | Front face oriented for direct gating. |

| Ingate Location | At base of front face. | Directly onto front face hot spot. |

| Runner Function | Slag trap & metal distribution. | Active feeder (Thermal reservoir). |

| Runner Modulus | Low ( ~1050 mm² area). | High (3650 mm² area). |

| Solidification Sequence | Hot spot isolated, unfed. | Progressive solidification towards feeder-runner. |

| Predicted Defect Risk | High (Shrinkage). | Very Low. |

Production trials were conducted with the new process parameters. The casting process was stable. Post-casting inspection, including X-ray radiography and final machining of the front face, confirmed the simulation’s prediction: no shrinkage cavities or porosity were detected in the critical front face area of the shell castings. The component met all dimensional and quality specifications. This optimized “feeder-runner” process was subsequently locked in and has been successfully used for series production, yielding consistent, high-quality transmission housings.

Conclusion

The development of a robust lost foam casting process for the complex three-intermediate-shaft transmission housing underscores the critical importance of integrated design, simulation, and empirical validation. The initial failure highlighted the limitations of applying standard gating rules to components with severe superposed thermal centers. The breakthrough came from fundamentally rethinking the function of the gating system—from merely a delivery channel to an active thermal management and feeding device.

The successful “feeder-runner” strategy satisfied the fundamental thermodynamic condition for sound shell castings:

$$ \frac{dV_{feed}}{dt} \geq \beta \cdot \frac{dV_{casting}}{dt} $$

where \( dV_{feed}/dt \) is the volumetric feed rate available from the runner, \( dV_{casting}/dt \) is the volumetric shrinkage rate of the casting, and \( \beta \) is a safety factor accounting for flow resistance. By ensuring the feeder-runner had a higher modulus and remained liquid longer, it provided the necessary feed metal to compensate for shrinkage throughout solidification.

This case study demonstrates that for challenging lost foam shell castings with thick sections and internal cavities, innovative gating design leveraging numerical simulation is not just beneficial but essential. The principles established here—direct hot spot gating combined with a high-modulus feeder section—provide a valuable framework for producing other complex, high-integrity cast components in gray iron and beyond.