In the realm of die casting production, the persistent issue of porosity in casting remains a critical challenge that directly impacts product quality, mechanical integrity, and yield rates. Throughout my extensive involvement in die casting processes, I have encountered numerous instances where gas porosity defects lead to significant scrap losses, particularly in complex structural components. This article aims to comprehensively explore the formation mechanisms, influencing factors, and preventive strategies for porosity in casting, drawing upon practical case studies and theoretical analyses. The focus will be on elucidating how gas entrapment occurs during metal injection, the role of die design, and the optimization of process parameters to mitigate these defects. By integrating empirical observations with fundamental principles, I intend to provide a detailed guide that enhances understanding and control over porosity in casting, ensuring the production of high-integrity die-cast parts.

Porosity in casting, specifically gas porosity, manifests as voids or holes within the cast structure, often originating from gases trapped during the molten metal’s journey from the melting furnace to the die cavity. These defects can severely compromise the part’s strength, pressure tightness, and machinability. The primary sources of gas that contribute to porosity in casting can be categorized into three distinct origins, as summarized in Table 1.

| Source Category | Description | Typical Defect Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Melting and Holding | Gases dissolved during melting (e.g., hydrogen, nitrogen) that are not sufficiently removed during degassing or refining processes. | Fine, dispersed pinholes or microscopic porosity, often uniformly distributed. |

| Filling Process Entrapment | Air or die lubricant vapors entrapped due to turbulent flow during cavity filling, leading to gas being carried into the liquid metal. | Larger, irregularly shaped gas pockets, frequently located in last-to-fill areas or near flow junctions. |

| Die Venting Inefficiency | Inadequate evacuation of air from the die cavity before and during metal injection, causing gas to be compressed and trapped. | Surface or subsurface blowholes, often concentrated in regions with poor venting pathways. |

The formation of porosity in casting is not merely a result of gas presence but a consequence of complex interactions between fluid dynamics, thermal conditions, and geometric constraints. To quantitatively analyze the filling process, we must consider the flow behavior of molten metal. The transition from laminar to turbulent flow is a critical determinant of gas entrainment. The Reynolds number ($Re$) provides a dimensionless parameter to predict this transition:

$$Re = \frac{\rho v D}{\mu}$$

where $\rho$ is the fluid density, $v$ is the flow velocity, $D$ is the hydraulic diameter, and $\mu$ is the dynamic viscosity. In die casting, when $Re$ exceeds a critical threshold (typically around 2000 for many alloys), turbulent flow ensues, dramatically increasing the likelihood of air entrainment and subsequent porosity in casting. This relationship underscores the importance of controlling injection speed to maintain $Re$ below this critical value whenever possible.

In practical terms, the filling speed of the molten metal into the die cavity is a paramount factor. Empirical studies and industry experience suggest that an optimal filling velocity exists to minimize turbulence. For instance, a target fill velocity of approximately 15 m/s is often cited for cold-chamber die casting of aluminum alloys to reduce porosity in casting. However, this value is not universal; it depends on alloy properties, gate design, and part geometry. The fill velocity ($v_f$) can be related to the shot sleeve velocity ($v_s$) and gate area ($A_g$) through the continuity equation:

$$v_f = \frac{v_s A_s}{A_g}$$

where $A_s$ is the shot sleeve cross-sectional area. Controlling $v_s$ via the injection profile is thus crucial. Modern machines allow for multi-stage injection curves, where an initial slow phase minimizes air entrapment, followed by a high-speed phase to complete filling, and finally a intensification phase to compress any remaining gases and feed shrinkage. The optimization of these stages is key to managing porosity in casting.

The design of the gating system profoundly influences the flow pattern and, consequently, the distribution of porosity in casting. Two common approaches are side gating and center gating, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Side gating, where metal enters from the periphery, can be beneficial for parts with long, thin sections, but it may lead to gas trapping in dead zones or last-fill areas. Center gating, where metal enters centrally, often promotes more directional solidification and can vent gases toward the periphery, but it may cause localized overheating or direct impingement on cores. Table 2 compares these gating strategies in the context of porosity in casting.

| Gating Type | Advantages Regarding Porosity | Disadvantages Regarding Porosity | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Side Gating | Allows for longer flow paths to vent gases sequentially; can reduce direct jetting. | May create turbulent junctions; dead zones at end of flow can trap gas. | Box-shaped parts, components with lateral features. |

| Center Gating | Promotes radial, more uniform flow; gases driven to outer vents; last-fill areas can be pressurized. | Risk of gas entrapment if flow symmetry is lost; can cause hot spots leading to shrinkage porosity. | Cylindrical parts, symmetric housings, parts requiring minimal machining. |

To further elucidate the impact of part geometry, consider a housing component with a internal spline groove. When using a side gate, the molten metal first fills the outer regions, potentially entrapping air in the spline area, which becomes a dead end. This often results in high concentrations of porosity in casting, sometimes up to 60-70% defect area upon machining. By switching to a center gate, metal directly enters near the spline region, making it part of the active flow path. This alteration allows gases to be displaced toward the outer perimeter where vents are located, significantly reducing porosity in casting. The effectiveness of such a change hinges on simulating or empirically verifying the fill pattern to ensure that the new gate location does not create other issues like cold shuts or excessive turbulence.

Another critical aspect is the role of die venting. Vents are essential pathways for air escape, but their design must balance exhaust capacity with prevention of metal leakage. The required vent area ($A_v$) can be estimated based on the volume of air to be displaced and the time available during filling. A simplified relation is:

$$A_v = \frac{V_a}{v_e t_f}$$

where $V_a$ is the air volume in the cavity, $v_e$ is the escape velocity of air through the vents (influenced by vent depth and back-pressure), and $t_f$ is the fill time. Insufficient vent area leads to back-pressure, compressing air and forcing it into the metal, thereby increasing porosity in casting. In practice, vents are often placed at the last points to fill and may include overflow wells to capture contaminated metal and entrapped gases.

Beyond gating and venting, the molten metal quality is foundational. Hydrogen solubility in aluminum alloys, for example, follows Sievert’s law:

$$[H] = K_H \sqrt{P_{H_2}}$$

where $[H]$ is the dissolved hydrogen concentration, $K_H$ is the solubility constant (temperature-dependent), and $P_{H_2}$ is the partial pressure of hydrogen. During solidification, hydrogen solubility drops sharply, causing gas to precipitate and form porosity in casting if the initial content is too high. Effective degassing using rotary impellers or inert gas purging is therefore essential to reduce hydrogen levels below a critical threshold, often specified as less than 0.1 ml/100g Al for high-quality castings.

Process parameters such as die temperature, metal temperature, and injection pressure also play synergistic roles. A higher die temperature can reduce premature solidification at the gates, allowing better cavity fill and gas evacuation, but it may increase cycle time and soldering risks. Metal temperature affects fluidity and gas solubility; optimal ranges must be maintained. Intensification pressure, applied after filling, helps compress residual gases and feed micro-shrinkage, thereby reducing the size and impact of porosity in casting. The required intensification pressure ($P_i$) can be derived from the ideal gas law and the solidification characteristics:

$$P_i \geq \frac{nRT}{V_g} + \Delta P_{feed}$$

where $n$ is moles of trapped gas, $R$ is the gas constant, $T$ is temperature, $V_g$ is gas volume, and $\Delta P_{feed}$ is the pressure needed to overcome feeding resistance. In practice, $P_i$ is often set as high as the machine and die can withstand, typically 500-1000 bar for aluminum die casting.

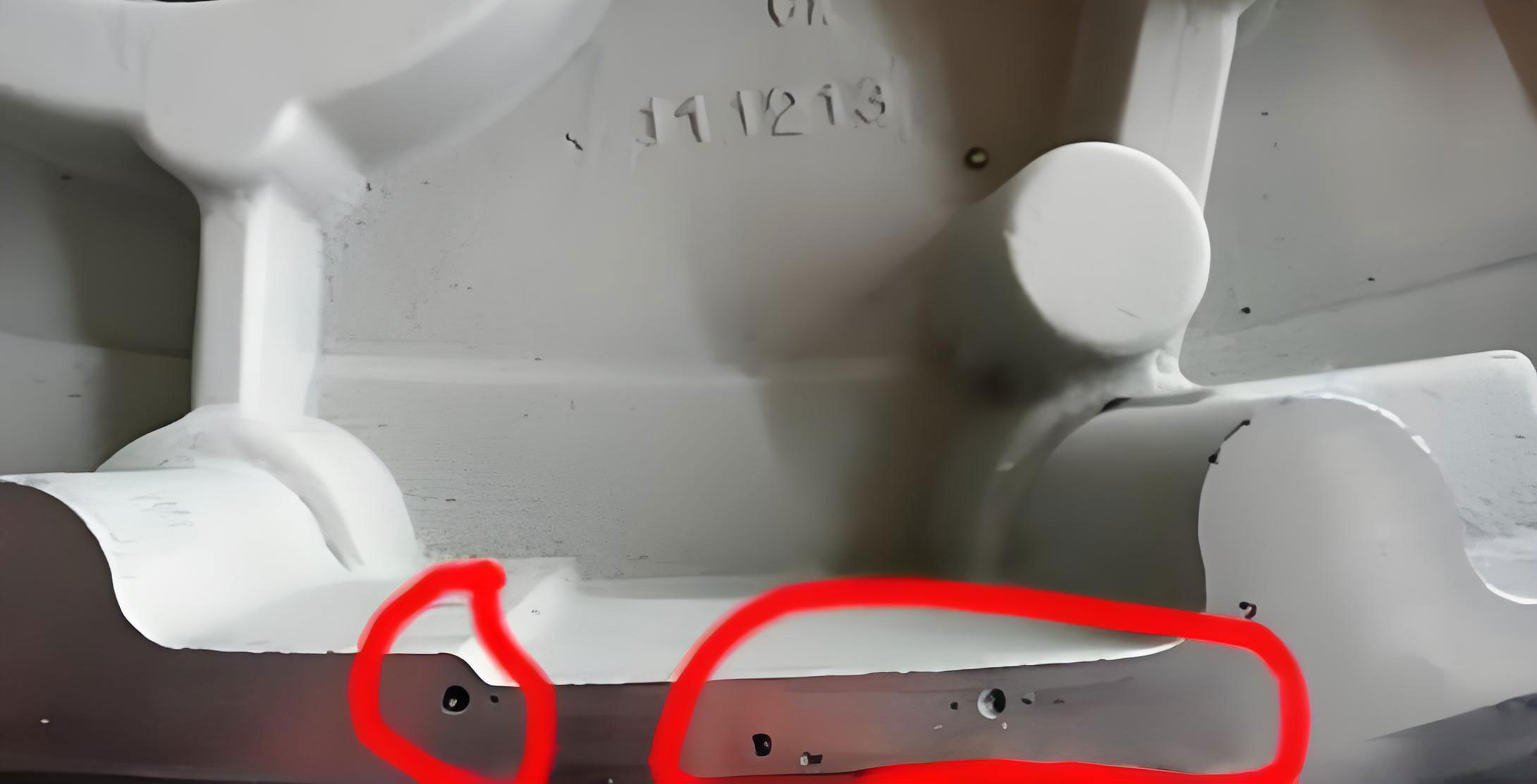

To illustrate these principles, let me detail a case study involving a structural housing. The initial design employed a side gate along a circumferential edge. After machining an internal feature, extensive porosity in casting was revealed, leading to high rejection rates. Analysis confirmed that the fill pattern created a dead zone in the feature area, where entrapped air could not escape. Initial corrective actions focused on improving die vents and enhancing degassing, which brought some improvement but not consistency. Subsequently, a thorough review of the filling dynamics was conducted. Using the concept of critical velocity, the shot profile was adjusted to reduce the first-phase injection speed, aiming for a more laminar flow. The fill velocity was approximated using the formula earlier, targeting around 15 m/s. This change reduced turbulent entrainment, but porosity in casting persisted intermittently.

The breakthrough came from re-evaluating the gating strategy. A switch to a center gate was proposed and implemented. This modification altered the flow sequence, making the previously problematic internal feature part of the main flow path rather than a dead end. As metal now reached this area earlier in the fill, gases were pushed toward peripheral vents. Small-scale trials showed a dramatic reduction in porosity in casting within the machined feature. However, it is crucial to note that center gating is not a universal solution. In another component with a central core pin, a center gate caused direct metal impingement, leading to localized overheating and shrinkage porosity combined with gas entrapment. For that part, a modified side gate with optimized runner geometry and overflows proved more effective. This highlights the necessity of a holistic approach where gating design is tailored to the specific part geometry and solidification pattern.

Advanced simulation software plays an increasingly vital role in predicting and mitigating porosity in casting. These tools solve the Navier-Stokes equations for fluid flow coupled with heat transfer and solidification models. Key outputs include fill patterns, temperature distributions, and porosity predictions. The porosity index ($PI$) in such simulations might be calculated based on factors like gas concentration and pressure drop:

$$PI = \int_{t_{fill}}^{t_{solid}} \left( \frac{\partial [G]}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (v [G]) \right) dt$$

where $[G]$ is the local gas concentration, $v$ is the fluid velocity, and the integration covers from filling to solidification. By iterating gate designs, vent placements, and process settings virtually, foundries can significantly reduce costly trial-and-error iterations, thereby proactively addressing porosity in casting.

Preventive measures for porosity in casting can be systematized into a multi-faceted strategy. Table 3 outlines a comprehensive checklist for die casting engineers to minimize gas-related defects.

| Category | Specific Action | Expected Impact on Porosity |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Preparation | Implement rigorous degassing (e.g., rotary degassing to <0.1 ml H2/100g Al). | Reduces gas dissolution source; minimizes pinhole porosity. |

| Die Design | Optimize gating (type, size, location) using flow simulation; ensure adequate vent area (0.1-0.3% of projected area); design overflows at last-fill zones. | Controls flow turbulence; facilitates air evacuation; traps gas-rich metal. |

| Process Parameters | Employ multi-stage injection: slow first phase (~0.2-0.5 m/s) to minimize air entrapment, followed by fast fill, and high intensification pressure (>500 bar). Control die temperature (150-200°C for Al) and metal temperature (e.g., 680-720°C for AlSi alloys). | Promotes laminar flow front; compresses residual gases; ensures proper fluidity. |

| Maintenance & Monitoring | Regularly clean and inspect vents for clogging; monitor lubricant application to avoid excessive vapor generation; calibrate shot end sensors for consistency. | Maintains consistent venting; reduces gas generation from lubricants; ensures repeatable shot profiles. |

In conclusion, porosity in casting is a multifaceted defect stemming from gas entrapment during the die casting process. Its formation is influenced by a confluence of factors: metal quality, filling dynamics, die design, and process parameters. Through detailed analysis and systematic optimization, significant reductions in porosity in casting can be achieved. Key takeaways include the importance of controlling fill velocity to avoid turbulence, selecting gating systems that align with part geometry to direct gases toward vents, ensuring thorough degassing of the molten metal, and applying sufficient intensification pressure. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, a methodical approach that combines theoretical understanding, simulation tools, and empirical validation offers the best path toward producing sound, high-integrity die castings. Future advancements in real-time process monitoring and closed-loop control may further enhance our ability to predict and eliminate porosity in casting, pushing the boundaries of quality and performance in die-cast components.