Porosity in casting is a pervasive and challenging defect encountered across all foundry processes. The V-process, or vacuum sealed molding, is no exception. Since its invention and subsequent adoption, the V-process has gained significant traction for producing complex, high-quality castings in various alloys. However, the unique characteristics of the process, primarily the use of a sealed plastic film and vacuum application, introduce specific challenges related to gas entrapment. Through extensive practical application and problem-solving, I have found that a systematic understanding and targeted measures can effectively control and eliminate porosity in V-process castings. This article consolidates insights into the classification, root causes, and comprehensive prevention strategies for different types of porosity in casting within the V-process context.

The battle against porosity in casting begins with accurate classification. Based on established metallurgical principles and the specific dynamics of the V-process, porosity can be categorized into five distinct types: entrapped gas porosity, invaded gas porosity, reaction gas porosity, precipitated gas porosity, and cavity-stagnation gas porosity. Each type has a unique formation mechanism, which dictates the appropriate countermeasures. The following sections delve into each category, presenting detailed analyses, preventive formulas, and summarized action plans.

1. Entrapped Gas Porosity

This type of porosity in casting originates from turbulent metal flow during pouring. Bubbles are engulfed by the molten metal stream and transported into the mold cavity. If these bubbles cannot escape before solidification, they become permanent defects. The V-process’s requirement for a fast, smooth fill to protect the EVA film often necessitates an open gating system, which inherently has poor gas expulsion capability, thus increasing the risk of entrapped gas porosity.

The core strategy is to design a gating system that minimizes turbulence. The cross-sectional areas are typically increased by approximately 30% compared to conventional sand casting to achieve the necessary rapid fill. The key relationship for an open system (common for steel castings) is:

$$F_{sprue} : \sum F_{runner} : \sum F_{ingate} = 1 : (1.2 \text{ to } 1.4) : (1.2 \text{ to } 2)$$

For a semi-open system (common for iron castings), the ingate is the choke:

$$F_{sprue} : \sum F_{runner} : \sum F_{ingate} = 1 : (1.2 \text{ to } 1.4) : (0.8 \text{ to } 1.4)$$

Critical operational details include positioning the pouring cup close to the ladle spout (ideally within three times the sprue diameter), pre-drying and heating the pouring cup, and ensuring a continuous pour without interruption. A key innovation is the use of a ceramic or sand core buffer well at the base of the sprue to absorb the impact energy of the metal stream, preventing splash and consequent gas entrainment. The design parameters for this well are often related to the sprue diameter (D): Well diameter $\phi_1 \approx 1.5D$, well depth $h \approx 0.5D$.

| Cause | Mechanism | Preventive Action |

|---|---|---|

| Turbulent flow in gating | Vortex formation draws air into metal stream. | Use enlarged, open/semi-open gating ratios; employ a buffer well. |

| Poor pouring practice | Interrupted pour, high fall height. | Maintain sprue full; minimize ladle-to-cup distance; use concentric pouring cups. |

| Leaks at pouring cup seal | Burning film allows air ingress. | Reinforce seal with backup films and clay. |

2. Invaded Gas Porosity

Invaded gas porosity in casting is formed when gases generated from the mold or core materials infiltrate the solidifying metal. While the V-process uses dry, binder-free sand which minimizes this source, other materials like the EVA film, coating, and cores remain significant gas generators.

The gas generation from the EVA film is inevitable but manageable by using thinner, high-quality films. The coating presents a major challenge. Alcohol-based coatings contain volatile solvents and resin binders that produce substantial gas upon heating. Control measures include stringent quality checks on coating powders and solvents, applying the minimum effective thickness, and, most crucially, thorough and uniform drying. Forced hot air drying (below 50°C) is far superior to radiant heating, as it ensures complete solvent evaporation from all cavity surfaces without damaging the film.

Cores, typically made from resin-bonded or CO2-silicate sand, are potent gas sources. Prevention focuses on material selection and gas venting. Using high-purity, rounded-grain sand (e.g., ceramic bead sand) can reduce resin/additive requirements by 30-50%, directly lowering gas potential. For large or high-gas-producing cores, installing dedicated vent pipes connected from the core print to the atmosphere outside the mold is essential. The vent pipe does not contact molten metal and can be reused. The sealing of the vent pipe through the EVA film is a critical detail to maintain vacuum integrity.

The gas evolution rate from a material can be considered as:

$$Q_{gas} = m \cdot \alpha(T)$$

where $Q_{gas}$ is the gas generation rate, $m$ is the mass of the material, and $\alpha(T)$ is a temperature-dependent gas evolution coefficient specific to the material (film, coating, core sand).

| Gas Source | Control Principle | Specific Measures |

|---|---|---|

| EVA Film | Minimize mass/area. | Use thin, high-grade film. |

| Casting Coating | Control quality, ensure complete drying. | Use high-pressure airless spray; enforce strict quality control on resins/solvents; dry with sub-50°C forced air. |

| Cores | Reduce gas generation, provide escape paths. | Use high-purity sand to lower binder content; use low-nitrogen resins for steel; pre-dry CO2-silicate cores; install vent pipes for large cores. |

| Moisture in compressed air | Eliminate water ingress during spraying. | Install effective air dryers and moisture traps on spray lines. |

3. Reaction Gas Porosity

This form of porosity in casting results from chemical reactions, either within the molten metal or at the metal-mold interface, producing insoluble gases. In ferrous castings, the primary reaction is the formation of carbon monoxide (CO):

$$[C]_{metal} + [O]_{metal} \rightarrow CO_{(g)} \uparrow$$

$$(FeO) + [C] \rightarrow Fe + CO_{(g)} \uparrow$$

The source of oxygen ([O]) or iron oxide (FeO) is the key. Therefore, the prevention strategy revolves around rigorous control of oxidation throughout the process, from charge materials to pouring.

Charge materials must be clean, dry, and free from rust (FeO·nH2O). The use of heavily rusted scrap or light-gauge oily steel should be minimized. During melting and holding, the metal surface should be covered with a slag coagulant to prevent air contact. In electric arc furnaces, proper slagging and refining are vital. For induction furnaces, which lack refining capability, effective deoxidation practice is paramount. This includes a pre-deoxidation sequence (e.g., with Fe-Mn and Fe-Si) based on bath analysis, followed by a final deoxidation with aluminum or complex deoxidizers, typically at 0.1% addition (not exceeding 0.3%).

A related defect is slag-associated porosity, where pores contain slag inclusions rich in FeO and MnO. The open gating of the V-process offers poor slag trapping. Solutions include strict charge control, effective metal cover, and the use of filtration. Ceramic foam filters or high-strength steel filter meshes, placed in the runner system with a total filter area greater than the sprue area, can effectively remove slag and reduce this type of reaction-related defect.

| Stage | Objective | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Preparation | Minimize oxide input. | Use clean, rust-free materials; limit recycled returns. |

| Melting & Holding | Prevent oxidation, remove oxides. | Cover metal surface with slag coagulant; perform proper slagging (EAF); execute timed pre-deoxidation and final deoxidation. |

| Pouring | Prevent re-oxidation, remove slag. | Minimize stream exposure to air; employ filters in gating system. |

4. Precipitated Gas Porosity

Precipitated gas porosity in casting is caused by the decreased solubility of gases (primarily hydrogen and nitrogen) in the metal as it solidifies. The gases come out of solution, forming bubbles. While related to melt chemistry, the V-process mold’s cooling rate can influence the final morphology of this porosity.

Hydrogen is frequently introduced via moisture. Key preventive measures are absolute dryness of all materials contacting the molten metal: charge materials, furnace linings, ladle linings, and tundishes. Preheating ladles to a minimum of 600°C is critical not only for safety and thermal management but also to drive off any residual moisture from the refractory that could dissociate into hydrogen. Nitrogen control, especially for steel castings, involves using charge materials with low nitrogen content and specifying low-nitrogen or nitrogen-free resins for any cores.

The solubility difference between liquid and solid states for a gas can be described by Sieverts’ law for diatomic gases like H2 and N2:

$$S = k \sqrt{P}$$

where $S$ is solubility, $k$ is a temperature-dependent constant, and $P$ is the partial pressure of the gas. During solidification, the constant $k$ drops sharply for the solid phase, leading to gas rejection and potential pore formation if the gas content is too high.

| Gas | Primary Source | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen (H2) | H2O from moisture. | Ensure dry charge, tools, and atmosphere; preheat ladles/linings thoroughly (>600°C). |

| Nitrogen (N2) | Charge materials, nitrogen-bearing resins. | Control charge nitrogen content; use low-N/no-N resins and binders for steel castings. |

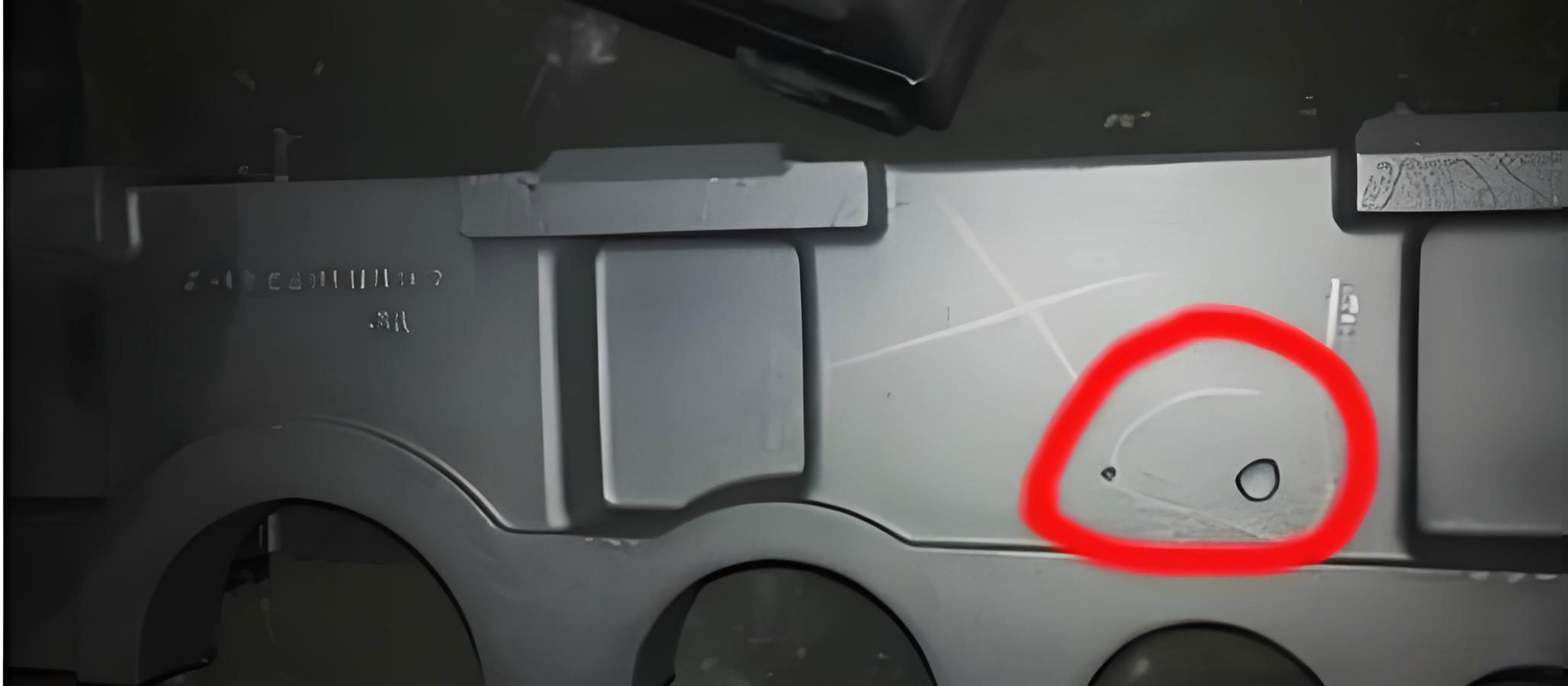

5. Cavity-Stagnation Gas Porosity

This is a particularly significant type of porosity in casting specific to the V-process, arising from the unique sealed cavity. The mold cavity, encapsulated by the plastic film, is essentially a closed volume. During pouring, as the metal rises, it sequentially seals off portions of the cavity. The original air inside, along with gases from burned film and coating in the un-filled upper cavity, becomes trapped, heated, and expands. If this high-pressure gas cannot escape, it can become entrapped in the metal (causing porosity), cause a “cough” or metal eruption, or even lead to mold collapse.

The solution is the strategic design of a venting system based on the concept of “gas chambers.” One must analyze how the cavity divides into separate sealed chambers as the metal rises. Each final gas chamber must be provided with at least one vent to the atmosphere. The total cross-sectional area of these vents ($\sum F_{vent}$) is critical and is proportional to the choke area of the gating system.

For thin-walled small castings:

$$\sum F_{vent} : F_{choke} = 1:1 \text{ to } 2:1$$

For thick-walled medium/large castings:

$$\sum F_{vent} : F_{choke} = 2:1 \text{ to } 3:1$$

where $F_{choke}$ is either the total ingate area (semi-open system) or the sprue area (open system).

For steel castings, vents can be larger and often combined with risers, as they are removed by cutting. For iron castings, especially ductile iron, numerous smaller vents are preferred to avoid creating shrinkage at the vent root due to the expansion phase of solidification. The thickness of a rectangular vent should be about 2/3 of the local casting wall thickness to allow easy mechanical removal. An effective technique is to extend vents from raised pads on the casting (core print extensions), placing the vent opening outside the final casting geometry, which improves venting efficiency and simplifies cleaning.

| Design Principle | Calculation/Guideline | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Chamber Analysis | Identify all sealed volumes formed during fill. | Provide at least one vent per final gas chamber. |

| Vent Sizing | $\sum F_{vent} = (1 \text{ to } 3) \times F_{choke}$ | Use larger ratio for thicker sections. |

| Vent Geometry & Placement | Steel: Fewer, larger, often combined with risers. Iron: More numerous, smaller sections. | Use extended pads to locate vent openings off casting body; rectangular vent thickness ≈ (2/3) × local wall thickness. |

In conclusion, combating porosity in V-process castings is a multi-front endeavor. Success hinges on correctly diagnosing the specific type of porosity in casting—whether it is entrapped, invaded, reaction-based, precipitated, or cavity-stagnation—and then implementing the tailored suite of technological and procedural countermeasures outlined. It requires diligent attention to every stage: from gating design and mold material control to rigorous melting practice and intelligent venting system design. The challenges posed by porosity in casting within the V-process are significant but not insurmountable. A disciplined, analytical approach focused on root cause elimination is the most effective path to producing sound, high-integrity castings.