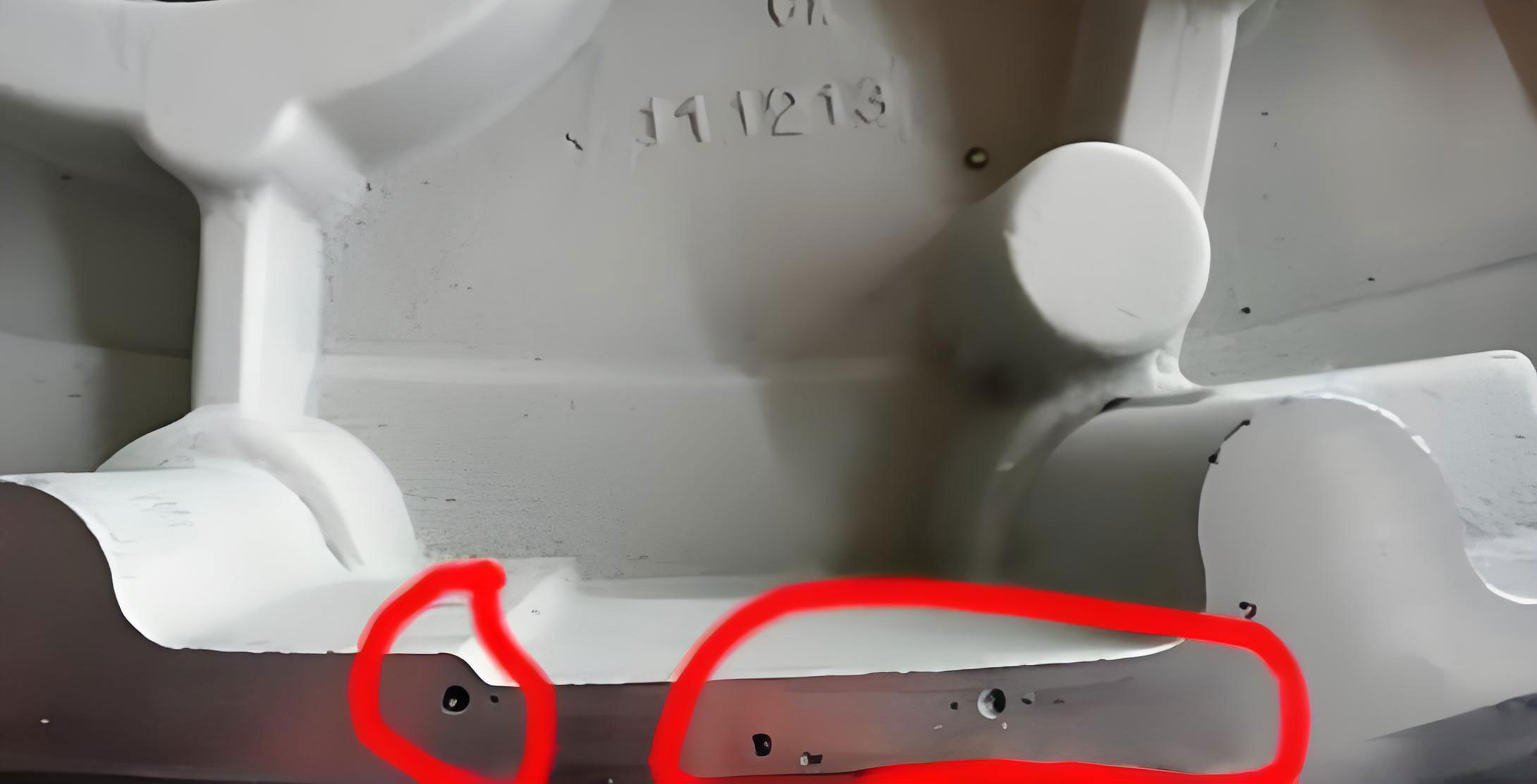

In our production facility, we encountered a persistent and costly challenge: a high scrap rate due to porosity in casting defects in a critical component known as the ZF oil inlet flange. This complex, thin-walled gray iron casting, with a nominal wall thickness of 7mm, is a supplied part demanding impeccable quality with machining allowances not exceeding 3mm and zero tolerance for any casting imperfections. The prevalent porosity in casting defects, primarily located at the top of cylindrical bosses and on flange faces, severely impacted production throughput and cost efficiency. This document details our systematic investigation into the root causes and the comprehensive process optimization measures we implemented to mitigate this issue.

The casting was produced using a no-bake resin sand molding process. The intricate internal cavities were formed by an assembly of cores: the main lower cavity core was produced via the cold-box process, while the upper cylindrical core and internal oil gallery cores were manufactured using a hot-box process with high-strength coated sand. The molds were coated with a water-based paint via overall dipping and dried in a conveyor oven. Melting was conducted in a medium-frequency induction furnace, and a closed gating system was employed. Despite this established process, the occurrence of gas-related porosity in casting remained unacceptably high.

A thorough analysis of the defect morphology, formation mechanisms, and process parameters led us to classify the primary defect as invasive gas porosity. This type of porosity in casting occurs when gases generated from the mold or core materials infiltrate the solidifying metal. Our investigation pinpointed three synergistic root causes:

- High Gas Evolution from Cores: The core assembly was a significant source of gases. The hot-box cores, made from high-strength coated sand necessary for the thin, complex shapes, exhibited particularly high gas evolution rates. The cold-box core also contributed substantially to the total gas load.

- High Gas Evolution from the Mold: The no-bake resin sand mold inherently generates gas during pouring. A critical sub-issue was identified with the deep cylindrical mold cavities (approximately 70mm in diameter and 134mm deep). The standard drying process failed to completely dry the water-based coating at the bottom of these deep pockets, leading to a localized surge of steam (gas) upon metal contact.

- Inadequate Venting of the Mold Cavity: The escape paths for gases generated within the core assembly were restricted. Venting was primarily limited to the core prints of the cylindrical core and the flange ring of the internal gallery core. Increasing the vent area on the flange ring was not a viable solution, as it risked causing mistruns (incomplete filling) on the casting.

The core of the problem can be summarized by the pressure balance at the metal-core interface. For gas to invade the metal, the local gas pressure (\(P_{gas}\)) must exceed the sum of the local metallostatic pressure (\(P_{metal}\)) and the pressure required to overcome the pore nucleation barrier (\(P_{nucleation}\)).

$$P_{gas} > P_{metal} + P_{nucleation}$$

Where \(P_{metal} = \rho g h\), with \(\rho\) being the metal density, \(g\) the acceleration due to gravity, and \(h\) the height of the metal column above the point in question. Our goal was to reduce \(P_{gas}\) by minimizing gas generation and facilitating its escape, thereby preventing the inequality from being satisfied.

Our strategy to eliminate the porosity in casting defects focused on a dual approach: aggressively reducing the source of gases and ensuring any remaining gases could exit the mold cavity efficiently. The following sections detail the specific process optimizations undertaken.

1. Reduction of Gas Evolution from Cold-Box Cores

The gas evolution of the cold-box core was identified as a modifiable parameter. We initiated experiments to adjust the ratio of the two-component resin system (Resin I and Resin II) while maintaining the minimum required tensile strength for safe core handling and casting integrity. The target tensile strength was set at \(\geq 1.0\, MPa\). We measured the gas evolution (in ml/g at a standard temperature) for different resin ratios. The results, summarized in Table 1, clearly indicated an optimal mix.

| Resin I : Resin II Ratio | Gas Evolution (ml/g) | 24-hour Tensile Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| 50 : 50 | 9.33 | 1.13 |

| 55 : 45 | 7.00 | 1.09 |

By shifting the ratio to 55:45, we achieved a significant 25% reduction in gas evolution (from 9.33 ml/g to 7.00 ml/g) while the core strength remained well above the 1.0 MPa threshold. This modification directly contributed to lowering the overall \(P_{gas}\) in the mold cavity, reducing the propensity for porosity in casting.

2. Development and Application of Low-Gas Evolution Coated Sand

The hot-box cores were the largest contributors to gas generation. The original “bead” coated sand had a gas evolution of 18 ml/g. We collaborated with our sand supplier to develop a specialized low-gas evolution coated sand formula. The development criteria required a balance: gas evolution must be minimized without compromising the core’s ability to withstand handling stresses and the initial thermal shock of metal pouring.

The relationship between binder content (a major contributor to gas), strength, and gas evolution can be conceptually modeled. The gas evolution (\(G\)) is often proportional to the organic binder content (\(B\)): \(G \propto k B\), where \(k\) is a constant for the specific binder. Strength (\(S\)) also relates to binder content, but not linearly, following a curve that plateaus. Our objective was to find the point on the \(S\) vs. \(B\) curve that met the minimum strength requirement (\(S_{min}\)) while minimizing \(B\) (and thus \(G\)).

The performance data for the original and newly developed sand are compared in Table 2. The results were exceptional.

| Coated Sand Type | Gas Evolution (ml/g) | 24-hour Tensile Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Original Bead Coated Sand | 18.0 | 3.10 |

| New Low-Gas Evolution Sand | 12.0 | 1.90 |

The new formula achieved a dramatic 33% reduction in gas evolution, bringing it down to 12 ml/g. Although the tensile strength decreased from 3.1 MPa to 1.9 MPa, it remained more than adequate for the application’s functional requirements. This change represented the single most impactful reduction in the potential for porosity in casting.

3. Optimization of Mold Coating and Drying Practice

To address the issue of incomplete drying in the deep, narrow mold cavities, we revised the coating application method. The original process of overall dipping in water-based paint was maintained for the general mold surface. However, for the two critical \(\phi 70mm \times 134mm\) deep cylindrical mold cavities, we introduced a supplementary manual operation.

- The deep cavities were manually coated with an alcohol-based (fast-drying) paint using a brush, ensuring complete coverage.

- Immediately after application, the alcohol-based coating was ignited to facilitate instant drying and hardening through combustion of the carrier solvent.

This hybrid coating strategy—overall water-based dip plus local alcohol-based brush-coat-and-burn—guaranteed that the surfaces most prone to trapping moisture (the deep cavity walls) were thoroughly dried. This eliminated a major local source of steam generation, effectively reducing \(P_{gas}\) at these critical locations and preventing localized porosity in casting.

4. Comprehensive Analysis of Improvement and Results

The implemented optimizations were not isolated fixes but a synergistic package targeting the root causes of gas generation. The cumulative effect on the system’s gas pressure can be conceptually expressed. The total gas pressure potential (\(P_{gas,total}\)) is a function of contributions from various sources:

$$P_{gas,total} = f(G_{cold-box}, G_{hot-box}, G_{mold-moisture}, V_{eff})$$

Where \(G\) terms represent gas evolution rates from cold-box cores, hot-box cores, and mold moisture, respectively, and \(V_{eff}\) represents the effectiveness of the venting system. Our actions directly reduced \(G_{cold-box}\), \(G_{hot-box}\), and \(G_{mold-moisture}\). While \(V_{eff}\) was not directly increased, reducing the gas generation load made the existing venting capacity significantly more effective.

The quantitative results, observed after full implementation from a baseline period, confirmed the success of our approach. The key performance indicators are summarized in Table 3.

| Performance Indicator | Pre-Improvement Baseline | Post-Improvement Result | Percentage Improvement/Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casting Scrap Rate due to Porosity | High (Reference 100%) | – | Reduction of 71% |

| Cold-Box Core Gas Evolution | 9.33 ml/g | 7.00 ml/g | Reduction of 25.0% |

| Hot-Box Core Gas Evolution | 18.0 ml/g | 12.0 ml/g | Reduction of 33.3% |

| Hot-Box Core Material Cost | High (Reference 100%) | – | Reduction of 70%* |

*Note: The new low-gas evolution coated sand was also significantly less expensive than the high-performance bead sand originally specified, yielding a major secondary benefit.

The 71% reduction in the scrap rate for porosity in casting defects translated directly into improved production efficiency, on-time delivery performance, and reduced quality costs. Furthermore, the change in coated sand material led to a substantial 70% reduction in the cost per ton for hot-box core production, delivering remarkable financial savings alongside the quality enhancement.

5. Conclusion and Generalized Principles

The successful resolution of the persistent porosity in casting problem in the ZF flange component underscores the importance of a systematic, root-cause-based approach in foundry process engineering. The problem was not merely a “gas defect” but a system imbalance involving multiple contributing factors. Our solution focused on the fundamental equation of invasive gas formation: we reduced the driving force (\(P_{gas}\)) by attacking it at its sources.

The key learnings and generalizable principles from this project are:

- Quantify and Characterize: Always measure material properties like gas evolution. Do not rely solely on supplier specifications or generic material names. Establish your own baseline data.

- Challenge Material Specifications: High-strength sands often come with high gas evolution. For non-structural cores or cores where the high strength is an over-specification, developing or sourcing a “fit-for-purpose” low-gas material is a highly effective strategy for combating porosity in casting.

- Understand Process Limitations: Standard drying cycles may not be effective for all geometric features in a complex mold. Identifying these “shadow zones” and implementing targeted solutions (like local fast-drying coatings) is crucial.

- Synergistic Solutions: The cumulative effect of multiple, smaller optimizations across different areas of the process (core making, mold preparation) can be far greater than a single large change. Reducing gas load makes the entire system more robust, even if venting is not modified.

- Cost-Benefit is Multifaceted: Process improvements aimed at quality, such as reducing porosity in casting, often yield direct financial benefits beyond scrap reduction, such as lower material costs, as demonstrated in this case.

In conclusion, controlling porosity in casting requires a holistic view of the mold cavity as a dynamic system involving gas generation, pressure buildup, and venting. By methodically analyzing each component of this system and implementing targeted, data-driven optimizations, we transformed a high-scrap casting into a reliable, cost-effective product. The principles applied here—material optimization, process adaptation, and systemic thinking—are universally applicable for tackling invasive gas defects in sand casting processes.