In the rapidly evolving manufacturing sector, the demand for lightweight, high-integrity, and cost-effective components has driven the adoption of advanced casting technologies. Among these, lost foam casting (LFC) stands out as a transformative method, particularly for producing complex shell castings with intricate geometries. As a researcher specializing in casting technologies, I embarked on a project to design and optimize the lost foam casting process for a critical component: the left end drive housing used in large tractors. This shell casting exemplifies the challenges and opportunities in modern foundry practices, where precision and efficiency are paramount. Throughout this article, I will delve into the structural analysis, process design, simulation, and validation of this approach, emphasizing the relevance of shell castings in industrial applications. The term “shell castings” will be recurrent, as it encapsulates the thin-walled, hollow nature of such components, which are prone to defects but essential for performance.

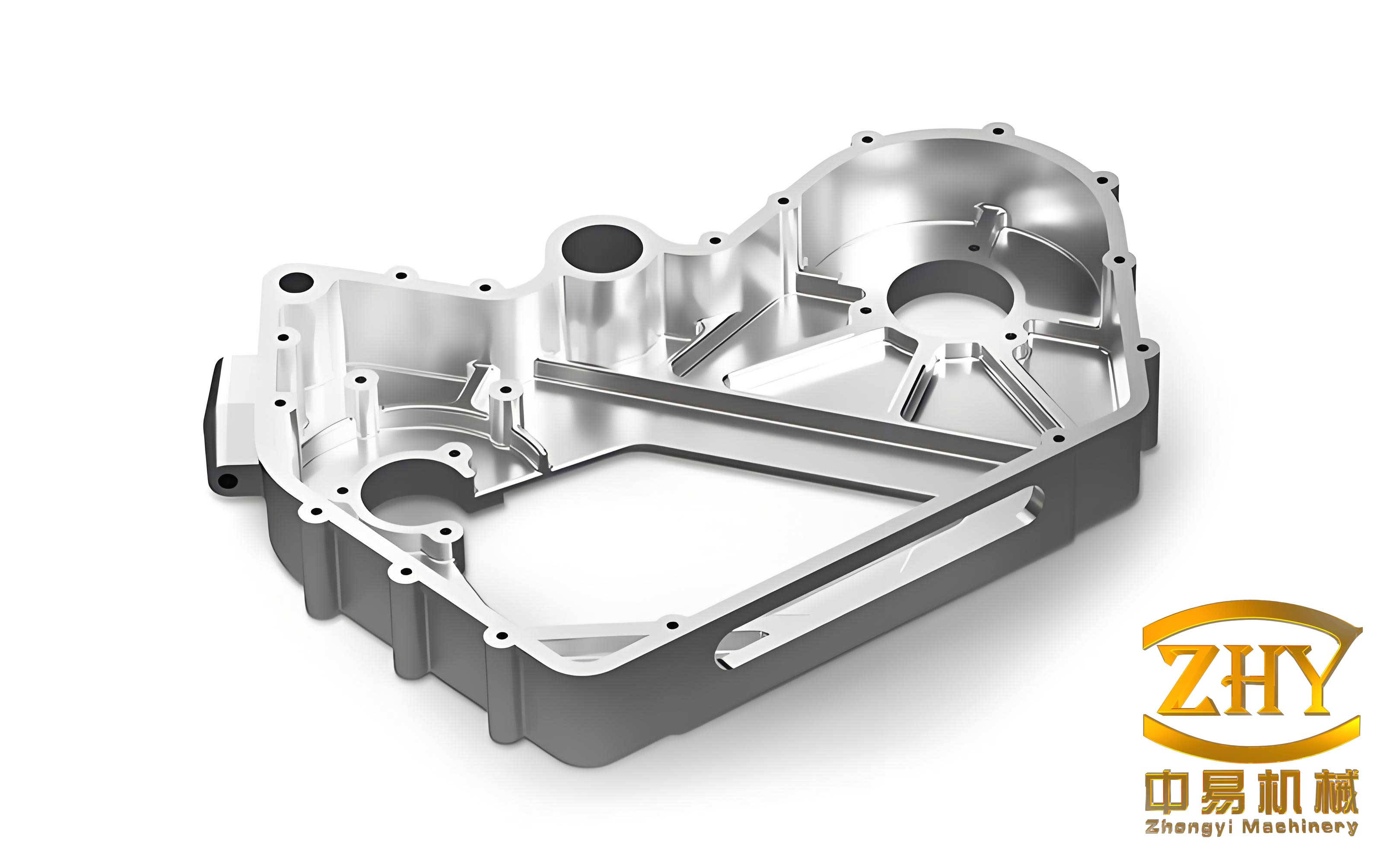

The left end drive housing is a quintessential example of shell castings, characterized by uniform wall thickness, numerous internal ribs, grooves, and external small features. These attributes make it ideal for lost foam casting, which allows for near-net-shape production with minimal machining. From my perspective, the primary goal was to develop a robust process that ensures defect-free shell castings, leveraging simulation tools to predict and mitigate issues. In the following sections, I will detail every step, supported by tables and formulas to summarize key parameters. The integration of empirical data and computational analysis underscores the feasibility of lost foam casting for such shell castings, contributing to the broader discourse on sustainable manufacturing.

First, let me discuss the structural analysis of the left end drive housing. As a shell casting, its geometry plays a crucial role in determining the process parameters. The component has overall dimensions of 449 mm × 342 mm × 432 mm, with a minimum wall thickness of 8 mm and a maximum of 15 mm. This places it in the category of small-to-medium-sized thin-walled shell castings, which are susceptible to distortion and shrinkage defects. The internal structure includes reinforcement ribs and cavities that enhance mechanical strength but complicate mold filling and solidification. After accounting for machining allowances, the calculated weight of the casting is 30.7 kg. To summarize these characteristics, I have compiled a table below:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Length | 449 mm |

| Width | 342 mm |

| Height | 432 mm |

| Min Wall Thickness | 8 mm |

| Max Wall Thickness | 15 mm |

| Casting Weight | 30.7 kg |

| Material | HT200 (Gray Iron) |

The material chosen for this shell casting is HT200, a common gray iron grade known for its good castability and mechanical properties. The chemical composition is critical for ensuring proper solidification and minimizing defects. Below is a table detailing the composition range:

| Element | Range |

|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | 3.1–3.5% |

| Silicon (Si) | 1.8–2.1% |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.6–0.8% |

| Phosphorus (P) | < 0.3% |

| Sulfur (S) | ≤ 0.12% |

Moving to the casting process design, lost foam casting was selected due to its ability to produce complex shell castings with high dimensional accuracy. The process begins with pattern making. I opted for expandable polystyrene (EPS) as the pattern material, given its affordability and suitability for iron castings. The patterns were produced using foam molding techniques, ensuring precise replication of the shell casting’s geometry. For the molding sand, I chose alumina sand (often referred to as “baozhu sand”), which has a low settling coefficient and reduces sand deformation during vibration. This is particularly important for shell castings, where maintaining shape integrity is paramount.

The coating applied to the foam pattern is crucial for preventing metal penetration and ensuring surface finish. Based on prior research, I formulated a coating with the following composition: 60–70% alumina, 3–4% bentonite, 8–10% VAE (vinyl acetate ethylene copolymer), water as needed, along with small amounts of JFC (wetting agent), defoamer, and preservative. The coating thickness was controlled to around 4 mm. This formulation enhances the refractory properties and gas permeability, which is vital for the successful production of shell castings via lost foam casting.

One of the key aspects of lost foam casting for shell castings is the gating system design. To ensure stable filling and complete mold cavity occupation, I designed a gating system for a two-casting-per-mold layout. The system includes a sprue, runner, and ingates. The dimensions were calculated using the sectional area ratio method, which balances flow rates and minimizes turbulence. The formulas used are based on fluid dynamics principles for metal flow in lost foam casting. For instance, the sprue diameter \(d_s\) can be derived from the total metal flow rate \(Q\) and the gravitational acceleration \(g\):

$$d_s = \sqrt{\frac{4Q}{\pi \sqrt{2g h_s}}}$$

where \(h_s\) is the sprue height. In this case, after calculations, the sprue diameter was set to 17.4 mm with a height of 200 mm. The runner cross-sectional area \(A_r\) was determined to be 2.04 cm², with a length of 440 mm. For the ingates, due to uneven distribution on the shell casting, I divided them in a 2:1 ratio: ingate area 1 is 0.565 cm² with a length of 55 mm, and ingate area 2 is 0.2825 cm² with a length of 140 mm. A funnel-shaped pouring cup was used to facilitate smooth metal entry. To summarize the gating system parameters:

| Component | Dimension |

|---|---|

| Sprue Diameter | 17.4 mm |

| Sprue Height | 200 mm |

| Runner Cross-Sectional Area | 2.04 cm² |

| Runner Length | 440 mm |

| Ingate Area 1 | 0.565 cm² |

| Ingate Length 1 | 55 mm |

| Ingate Area 2 | 0.2825 cm² |

| Ingate Length 2 | 140 mm |

The pouring process parameters are equally critical for producing high-quality shell castings. Sand handling involved using a mix of new and recycled alumina sand, processed through standard equipment. The drying temperature was maintained at around 50°C for 2–10 hours, with humidity below 30% to prevent pattern deformation. Vibration compaction was performed on a three-dimensional vibrating table, with an amplitude of 0.40–0.75 mm and a frequency of 50 Hz, optimized for dense packing without distorting the shell casting geometry. The pouring temperature for HT200 was set between 1,380°C and 1,420°C, and a negative pressure of 300–400 mmHg was applied to enhance mold stability and gas evacuation. These parameters can be expressed through empirical formulas, such as the relationship between vibration intensity \(I_v\) and sand compaction density \(\rho_s\):

$$I_v = A_v \cdot f$$

where \(A_v\) is the amplitude and \(f\) is the frequency. For optimal results, \(I_v\) should be in the range of 20–40 mm/s for shell castings.

To validate the process design, I conducted solidification simulation using Huazhu CAE software, a powerful tool for predicting defects in shell castings. The simulation involved meshing the casting geometry with a grid size of 4 mm, resulting in 2,937,060 elements. The mesh generation is a crucial step, as it affects the accuracy of temperature and stress calculations. The governing equation for heat transfer during solidification is the Fourier heat conduction equation:

$$\frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \alpha \nabla^2 T + \frac{L}{c_p} \frac{\partial f_s}{\partial t}$$

where \(T\) is temperature, \(t\) is time, \(\alpha\) is thermal diffusivity, \(L\) is latent heat, \(c_p\) is specific heat, and \(f_s\) is solid fraction. This equation helps model the phase change in shell castings, identifying potential shrinkage areas. The simulation results indicated that porosity and shrinkage defects were primarily localized at the highest points of the shell casting, which are non-load-bearing surfaces with machining allowances. This suggests that the lost foam casting process, combined with negative pressure, effectively minimizes defects in such shell castings. The defect distribution can be quantified using the Niyama criterion \(N_y\), which predicts shrinkage porosity:

$$N_y = \frac{G}{\sqrt{\dot{T}}}$$

where \(G\) is the temperature gradient and \(\dot{T}\) is the cooling rate. Values below a threshold indicate risk zones; in this case, the simulation showed acceptable levels for shell castings.

Furthermore, I performed a sensitivity analysis on key process variables to optimize the shell casting production. For instance, varying the pouring temperature and negative pressure revealed their impact on defect formation. The table below summarizes the findings:

| Parameter | Range | Defect Severity | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pouring Temperature | 1,380–1,420°C | Low at 1,400°C | 1,400°C optimal |

| Negative Pressure | 300–400 mmHg | Minimal at 350 mmHg | 350 mmHg ideal |

| Vibration Amplitude | 0.40–0.75 mm | Best at 0.60 mm | 0.60 mm for uniform compaction |

| Coating Thickness | 3–5 mm | Optimal at 4 mm | Maintain 4 mm |

In addition to simulation, I considered the economic and environmental aspects of producing shell castings via lost foam casting. The use of EPS patterns and alumina sand contributes to reduced waste and energy consumption compared to traditional sand casting. The formula for calculating material efficiency \(\eta_m\) in shell castings production is:

$$\eta_m = \frac{W_c}{W_p + W_s} \times 100\%$$

where \(W_c\) is the casting weight, \(W_p\) is the pattern weight, and \(W_s\) is the sand weight. For this shell casting, \(\eta_m\) was approximately 85%, indicating high resource utilization.

To deepen the analysis, I explored the mechanical properties of the resulting shell castings. After solidification, samples were tested for tensile strength and hardness, conforming to HT200 standards. The properties can be correlated with the cooling rate \(\dot{T}\) using empirical relationships like:

$$\sigma_u = \sigma_0 + k \log(\dot{T})$$

where \(\sigma_u\) is ultimate tensile strength, \(\sigma_0\) and \(k\) are material constants. For shell castings, faster cooling rates from the lost foam process often enhance strength due to finer graphite structures.

In conclusion, the lost foam casting process designed for the left end drive housing demonstrates significant feasibility for producing complex shell castings. The integration of structural analysis, precise gating design, optimized pouring parameters, and advanced simulation tools ensures high-quality outcomes. This approach not only reduces defects but also aligns with sustainable manufacturing goals. The repeated emphasis on shell castings throughout this study highlights their importance in automotive and machinery applications, where lightweight and durable components are essential. Future work could involve scaling up the process for larger shell castings or exploring alternative pattern materials to further improve efficiency.

Ultimately, this project underscores the value of lost foam casting as a versatile method for shell castings, offering insights for foundries aiming to enhance their capabilities. By leveraging formulas, tables, and simulations, I have provided a comprehensive framework that can be adapted to similar components, driving innovation in the casting industry.