In the rapidly evolving manufacturing landscape, the production of high-integrity, complex shell castings has become increasingly critical for applications in automotive, agricultural machinery, and industrial equipment. Shell castings, characterized by their often intricate internal geometries, uniform wall thicknesses, and external detailing, present significant challenges for conventional casting methods. Lost foam casting (LFC), also known as evaporative pattern casting, emerges as a particularly suitable advanced manufacturing technology for such components. This process, which involves the use of a vaporizable foam pattern embedded in unbonded sand, offers distinct advantages in terms of dimensional accuracy, design flexibility, and reduced machining needs for shell castings. In this comprehensive analysis, I will delve into the detailed design of a lost foam casting process tailored for the production of shell castings. The discussion will encompass structural analysis, material selection, gating and pouring system design, process parameter optimization, and the critical role of solidification simulation in validating the feasibility of the process for producing sound shell castings.

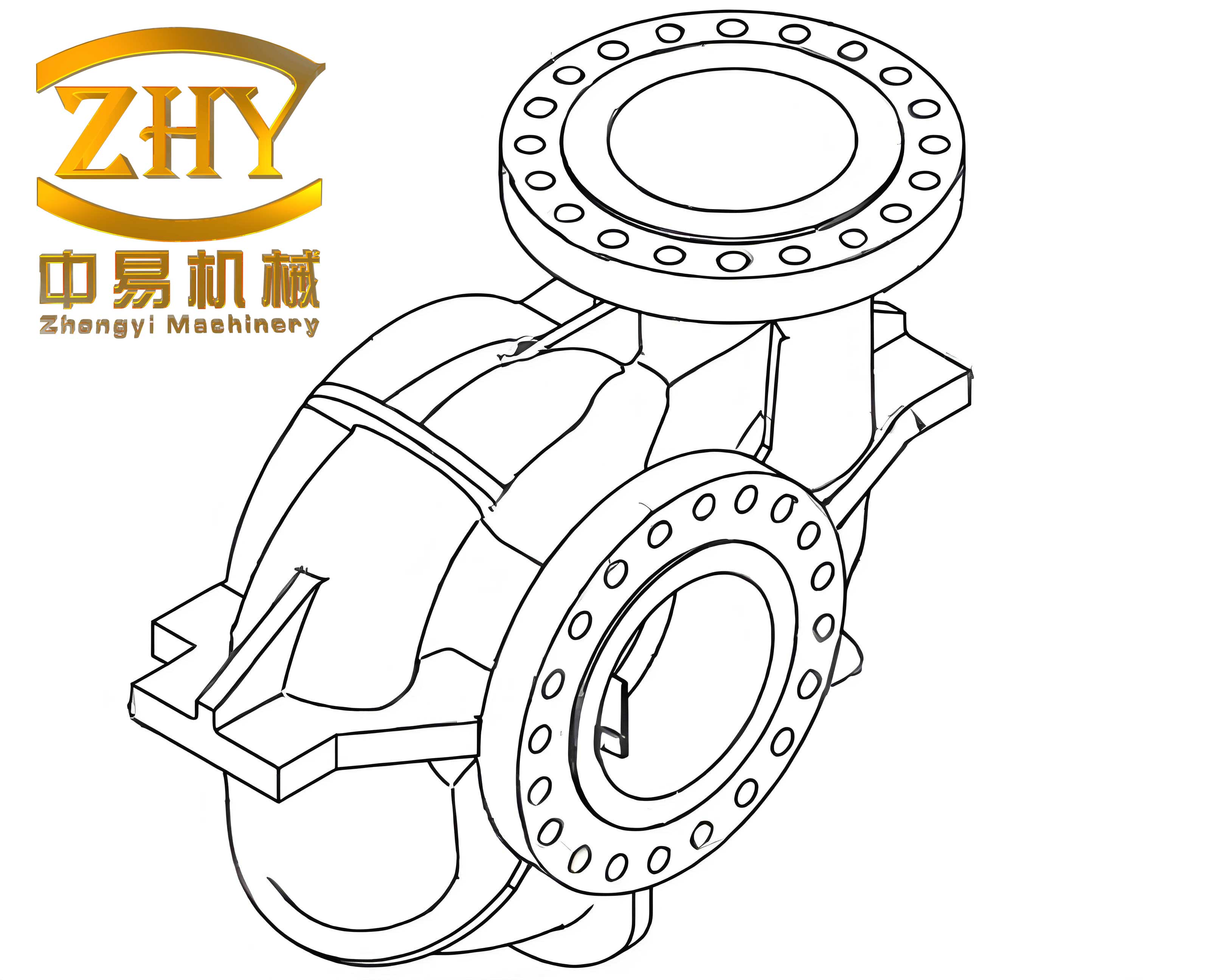

Shell castings, by their very nature, are designed to enclose and support mechanical assemblies, often featuring a combination of thin walls, internal reinforcing ribs, bosses, and external mounting points. A typical drive housing shell casting, for instance, might have overall envelope dimensions in the range of 450 mm x 350 mm x 430 mm. The wall thickness in such shell castings is usually designed to be as uniform as possible to ensure consistent mechanical properties and avoid stress concentrations, commonly ranging from 8 mm to 15 mm. The presence of numerous internal ribs and channels, which are essential for structural rigidity and fluid or component routing, makes the casting process challenging due to the potential for mist runs, gas entrapment, and shrinkage defects. The casting weight, after incorporating necessary machining allowances for final dimensions and non-cast features like threaded holes, typically falls around 30 kg for midsize components. The material of choice for many such structural shell castings is gray iron, specifically grades like HT200, which offers an excellent balance of castability, machinability, damping capacity, and cost-effectiveness. The standard chemical composition for HT200 gray iron is summarized in Table 1.

| Element | Minimum | Maximum | Target Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.2–3.4 |

| Silicon (Si) | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.9–2.0 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.65–0.75 |

| Phosphorus (P) | – | 0.30 | < 0.15 |

| Sulfur (S) | – | 0.12 | < 0.10 |

The successful production of shell castings via lost foam casting hinges on a meticulously designed process chain. The first and foundational step is the creation of the expendable pattern. For iron-based shell castings, expandable polystyrene (EPS) is the most widely used pattern material. Its advantages are multifold: low cost, ease of processing into complex shapes through bead fusion in aluminum molds, and a clean, controlled decomposition profile when contacted by molten metal. The pattern for a shell casting is typically manufactured as multiple segments if the geometry is highly complex, which are then assembled using hot-melt adhesives to form a complete replica of the final part, including the integrated gating system. This assembly, known as the pattern cluster, is crucial for ensuring the dimensional fidelity of the final shell casting.

Following pattern assembly, the application of a refractory coating is paramount. This coating serves several vital functions: it prevents metal penetration into the sand mold, provides a smooth surface finish on the shell casting, enhances pattern strength during handling, and controls the rate of gas evolution from the decomposing foam. For gray iron shell castings, a water-based coating with a high refractory aggregate content is standard. A proven formulation includes 60–70% alumina (Al2O3), 3–4% bentonite as a binder, 8–10% vinyl acetate ethylene (VAE) copolymer as a film-forming agent, and small additions of wetting agents (e.g., JFC), defoamers, and biocides. The coating is applied via dipping or spraying to achieve a uniform thickness, typically targeted at 0.5 to 1.0 mm per coat, with a total dried thickness of 1.5 to 2.0 mm. Drying is conducted in a well-ventilated oven at temperatures around 50±5°C for a duration sufficient to reduce the moisture content below 1%, often between 4 to 8 hours depending on cluster size and humidity.

The next critical phase is mold preparation. The dried, coated pattern cluster is placed in a flask, which is then filled with dry, unbonded sand. The choice of sand is significant for shell castings to maintain geometric stability. Ceramic sands like zircon or alumina-silicate based “baozhu” sand (fused ceramic beads) are preferred over silica sand for several reasons: higher thermal stability, lower thermal expansion coefficient, excellent flowability, and high permeability. These properties are crucial for complex shell castings to minimize veining and penetration defects while allowing gases from foam decomposition to escape easily. The sand is compacted around the fragile pattern using three-dimensional vibration. The optimal vibration parameters to achieve uniform compaction without pattern distortion for shell castings are an amplitude in the range of 0.4–0.75 mm and a frequency of 50–60 Hz. The degree of compaction can be quantified by the bulk density achieved, often targeting values above 1.6 g/cm³ for ceramic sands.

The heart of the casting process design lies in the gating and feeding system. For shell castings produced via lost foam casting, a pressurized gating system is often employed to ensure rapid and complete filling of the thin sections before the foam degradation front advances too far. The design is based on the concept of gating ratios (sprue area : runner area : total ingate area). For the aforementioned shell casting example, a systematic calculation leads to the following dimensions. The pouring time $t_p$ for a cast iron casting can be estimated empirically. One common formula is:

$$ t_p = k \cdot \sqrt{W} $$

where $W$ is the casting weight in kg and $k$ is an empirical coefficient (typically 1.8-2.2 for iron). For a 30.7 kg shell casting, $t_p$ is approximately 10 seconds. The required metal flow rate $Q$ is then $W / t_p \approx 3.07 \, \text{kg/s}$. Assuming a theoretical pouring velocity $v$ at the sprue base (derived from Bernoulli’s principle under a negative pressure head $P_{vac}$ and metallostatic head $h$), the sprue cross-sectional area $A_s$ is given by:

$$ A_s = \frac{Q}{\rho_{Fe} \cdot v} = \frac{Q}{\rho_{Fe} \cdot \sqrt{2gh + \frac{2P_{vac}}{\rho_{Fe}}}} $$

where $\rho_{Fe}$ is the density of liquid iron (~7000 kg/m³), and $g$ is gravitational acceleration. For practical design, simplified charts or software are used. The resulting gating system dimensions for this shell casting are detailed in Table 2.

| Gating Component | Symbol | Calculated Value | Design Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sprue Top Diameter | $d_{s,t}$ | 16.8 mm | 17.0 mm |

| Sprue Bottom Diameter | $d_{s,b}$ | 19.1 mm | 19.0 mm (tapered) |

| Sprue Height | $h_s$ | – | 200 mm |

| Runner Cross-sectional Area | $A_r$ | 204 mm² | 200 mm² (10 mm x 20 mm) |

| Runner Length | $L_r$ | – | 440 mm |

| Total Ingate Area | $A_{i,total}$ | 85 mm² | 85 mm² |

| Ingate 1 Area (2 nos.) | $A_{i1}$ | 56.5 mm² each | 57 mm² each |

| Ingate 2 Area (2 nos.) | $A_{i2}$ | 28.25 mm² each | 28 mm² each |

A key decision in the process design for these shell castings is the adoption of a feederless (riserless) approach. This is often feasible in lost foam casting for shell castings with relatively uniform wall thickness due to the nature of the process. The slow, progressive metal advance and the presence of the foam pattern create a favorable temperature gradient, and the applied negative pressure can help feed shrinkage through the gating system until it solidifies. This eliminates the need for additional feeders, improving yield and simplifying pattern cluster design.

The pouring operation itself is governed by critical parameters. For HT200 shell castings, the superheat must be carefully controlled. A pouring temperature range of 1380–1420°C is typical. The lower end minimizes thermal shock to the foam and reduces liquid contraction, while the higher end ensures fluidity to fill thin sections. The mold is subjected to a vacuum (negative pressure) typically between -0.04 to -0.05 MPa (300–400 mmHg) throughout pouring and until the casting has solidified sufficiently. This vacuum serves multiple purposes: it stabilizes the unbonded sand mold, accelerates the removal of pyrolysis gases from the decomposing foam through the permeable coating and sand, and can enhance metal feeding. The kinetics of foam decomposition is complex and can be approximated by an Arrhenius-type equation for the degradation rate $r$:

$$ r = A \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{R T}\right) $$

where $A$ is the pre-exponential factor, $E_a$ is the apparent activation energy for EPS degradation, $R$ is the universal gas constant, and $T$ is the local temperature at the metal-foam interface. The negative pressure ensures these gaseous products are quickly drawn away from the advancing metal front, preventing porosity in the shell casting.

To scientifically validate the designed process and predict potential defects in the shell castings, numerical simulation of the coupled filling and solidification processes is indispensable. I employ a commercial casting simulation software based on finite difference methods. The first step is geometric discretization. For a shell casting with dimensions around 450mm, a mesh size of 4mm provides a good balance between computational accuracy and time. This results in a high number of computational cells, often exceeding 2.5 million for the casting, mold, and gating system combined. The governing equations for heat transfer during solidification are solved iteratively. The transient heat conduction equation with a latent heat source term is central:

$$ \rho(T) c_p(T) \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot \left( k(T) \nabla T \right) + \rho(T) L \frac{\partial f_s}{\partial t} $$

Here, $\rho$ is density, $c_p$ is specific heat, $k$ is thermal conductivity, $T$ is temperature, $t$ is time, $L$ is the latent heat of fusion, and $f_s$ is the solid fraction. For gray iron, which solidifies via a eutectic reaction with graphite precipitation, the release of latent heat is often treated using a temperature interval method between the liquidus $T_l$ and solidus $T_s$. A linear relationship is sometimes assumed: $f_s = (T_l – T)/(T_l – T_s)$ for the eutectic portion. The boundary conditions include the heat transfer coefficient $h$ at the metal-mold interface, which in lost foam casting is influenced by the evolving gas gap from the decomposing foam. A time-varying $h$ model is often used, starting high and decreasing as the gap forms. Typical simulation input parameters are consolidated in Table 3.

| Parameter Category | Symbol | Value / Model |

|---|---|---|

| Material (Casting) | – | HT200 Gray Iron |

| Liquidus Temperature | $T_l$ | ≈ 1200°C |

| Solidus Temperature | $T_s$ | ≈ 1150°C |

| Latent Heat of Fusion | $L$ | ≈ 270 kJ/kg |

| Initial Mold Temperature | $T_{mold,0}$ | 25°C (Ambient) |

| Pouring Temperature | $T_{pour}$ | 1400°C |

| Interface Heat Transfer Coeff. | $h_{interface}$ | Variable, 500 → 100 W/m²·K |

| Computational Grid Size | $\Delta x, \Delta y, \Delta z$ | 4.0 mm |

| Simulation Software | – | Commercial FDM-based CAE System |

The simulation output provides critical insights into the thermal history of the shell casting. Contour plots of solidification time reveal the sequence in which different sections freeze. The fundamental criterion for predicting shrinkage porosity is the thermal gradient $G$ and the local solidification time $t_{loc}$. The Niyama criterion, often adapted for cast irons, is a useful indicator. It is defined as $Ny = G / \sqrt{\dot{T}}$, where $\dot{T}$ is the cooling rate. Areas with a Niyama value below a critical threshold (e.g., ~1 °C1/2·min1/2/cm for some irons) are flagged as potential shrinkage porosity sites. For the designed gating system on the example shell casting, the simulation results consistently show that the last regions to solidify are small, isolated thermal masses at the top of the casting, such as the tops of mounting bosses or the junction where the gating system meets the casting. Importantly, these areas are non-load-bearing and are subsequently machined away during final processing. The main body of the shell casting, with its relatively uniform wall thickness, solidifies in a progressive manner, demonstrating a favorable temperature gradient from the thin walls towards the initially hotter metal entering through the ingates. This directional solidification pattern, aided by the cooling effect of the massive foam pattern during filling, minimizes mid-wall shrinkage and promotes soundness in the critical sections of the shell casting.

Beyond shrinkage, the simulation can also assess potential for other defects specific to lost foam casting of shell castings. These include carbon defects (due to incomplete foam degradation) and fold defects (due to metal front turbulence). By analyzing the temperature and velocity fields during filling, one can ensure that the metal front advances smoothly and that the foam pyrolysis gases are efficiently evacuated, which is confirmed by the pressure field simulation under the applied vacuum.

The convergence of the simulation results with practical experience forms a robust validation loop. Minor adjustments to the process, such as slightly increasing the pouring temperature by 10°C or optimizing the ingate locations based on simulated flow paths, can be evaluated virtually before committing to costly physical trials. This iterative simulation-based design process significantly de-risks the production launch for complex shell castings.

In conclusion, the lost foam casting process presents a highly viable and efficient manufacturing route for producing complex, thin-walled shell castings. Through a systematic design approach that includes careful pattern material (EPS) selection, optimized refractory coating formulation, strategic use of high-quality unbonded sands, and a scientifically designed gating system operating under controlled vacuum, high-integrity shell castings can be reliably produced. The adoption of a feederless scheme for appropriately designed shell castings further enhances material yield and economic efficiency. Crucially, the integration of solidification process simulation into the design phase provides an objective, accurate, and predictive tool to validate the process feasibility. It identifies potential defect zones, confirms the effectiveness of the designed thermal gradients, and ultimately builds confidence that the shell castings will meet their mechanical and dimensional specifications. As manufacturing trends continue to demand lighter, stronger, and more geometrically intricate components, the synergy between lost foam casting technology and advanced numerical simulation will remain indispensable for the cost-effective and quality-conscious production of shell castings across various industries.