Abstract

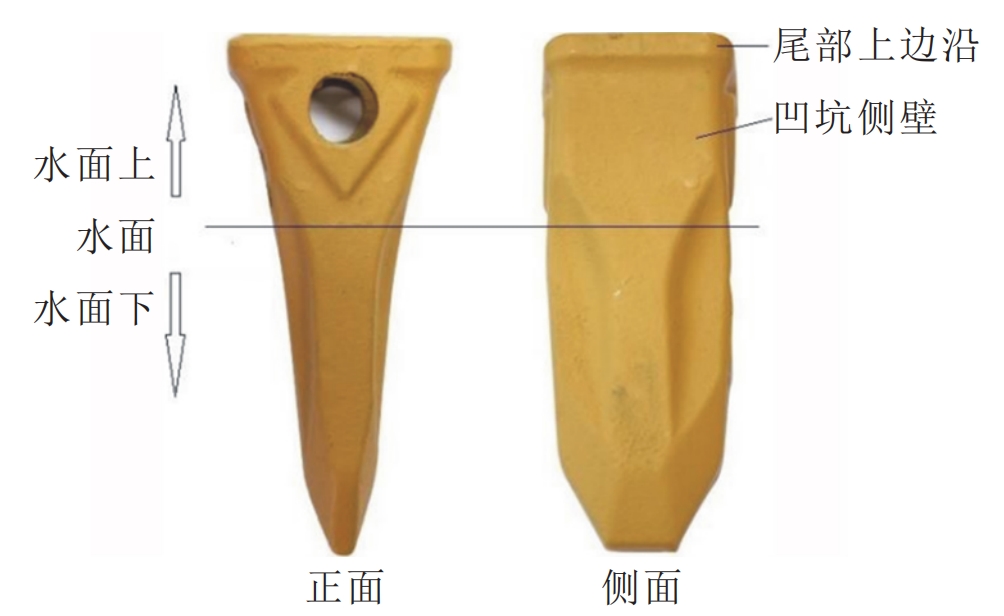

This study focuses on the production process of forged 30CrMnSi steel bucket teeth, involving forging and forging residual heat quenching. Hardness tests were conducted on the cut bucket teeth, and impact specimens were taken from the tail (vulnerable to fracture during use) for impact testing. The fracture morphology and microstructure were observed to investigate the effects of forging and heat treatment processes on the mechanical properties and microstructure of the bucket teeth. The results revealed that the hardness and impact energy of different parts of the forged 30CrMnSi steel bucket teeth varied significantly. Specifically, the hardness at the tip and near the pit was lower, and the impact energy of the pit sidewall was notably lower than that of the upper edge of the tail. This was attributed to the high final forging temperature and the relatively enclosed pit area, which resulted in poor cooling conditions and coarse grains at the pit sidewall, significantly reducing the impact energy.

Keywords: 30CrMnSi steel; Forging residual heat quenching; Hardness; Impact energy

1. Introduction

Bucket teeth are essential wear parts of excavators. During operation, bucket teeth not only endure severe abrasive wear but also bear impact loads, leading to short service lives and high consumption rates. In China, wear of bucket teeth causes approximately 30 million yuan in economic losses annually. Additionally, indirect economic losses due to downtime and production halts caused by wear and fracture of bucket teeth are even more significant. To adapt to mining excavation demands, excavators directly contact ores, sand, soil, rocks, and other materials, operating under harsh conditions. Therefore, bucket teeth are required to possess high hardness, wear resistance, and good toughness.

The forming processes for bucket teeth mainly include casting and forging. Most bucket teeth produced in China are cast due to their low cost, simple process, and ease of mass production, making them the dominant product in the market. However, cast bucket teeth exhibit coarse microstructures and numerous defects such as inclusions, segregation, shrinkage porosity, and shrinkage cavities, which cannot be eliminated through subsequent heat treatment processes. In contrast, forged bucket teeth have unbroken fiber structures, finer grains, and no segregation or inclusion defects, resulting in better mechanical properties. Forged bucket teeth exhibit excellent comprehensive mechanical properties.

This study focuses on the microstructure and properties of forged 30CrMnSi steel bucket teeth. The production process, including forging and forging residual heat quenching, was investigated. Hardness tests were performed on various parts of the bucket teeth, and impact specimens were taken from the tail for impact testing. The fracture morphology and microstructure were observed to explore the effects of forging and heat treatment processes on the mechanical properties and microstructure of the bucket teeth, aiming to provide guidance for process improvement.

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1 Production Process of Forged Bucket Teeth

The specific dimensions of a certain type of bucket tooth are as follows: total height of 286 mm, length and width of the tail edge (external) of 116 mm × 109 mm, and width and thickness of the tooth tip of 41 mm × 13 mm, with a weight of 7 kg. The raw material was a φ75 mm 30CrMnSi steel bar, and its measured chemical composition is shown in Table 1.

The specific forging and heat treatment process flow is as follows: blanking → induction heating → forging the tip → die forging → punching and trimming → punching the pin hole → stamping → forging residual heat quenching → low-temperature tempering → sandblasting. Forging residual heat quenching refers to a process where the workpiece is quenched in a quenching medium immediately after forging while the temperature is still above Ac3, obtaining a quenched structure. The quenching medium used was water. The specific forging residual heat quenching process involved hanging the entire bucket tooth into the water (with the lifting rod hooked on the pin hole) and shaking it for approximately 10 seconds, then exposing the tail (upper part) above the water surface for about 10 seconds (to reduce the hardness of the upper part and improve its impact toughness), and finally immersing the entire bucket tooth in the water until it cooled to approximately 350°C before removing it from the water to complete the quenching process.

2.2 Performance Testing

A normally produced bucket tooth of a certain model was taken, and it was cut using wire cutting. Specifically, the bucket tooth was first cut into two parts (horizontally along the dotted line), and the lower part was further cut into three parts (vertically along the dotted lines). The middle part was then polished smooth using a grinder and sandpaper, and Rockwell hardness tests were performed at the test points. Six impact specimens were taken from the tail (upper part) of the forged bucket tooth, with two specimens cut transversely (numbered 5 and 6) and four specimens cut longitudinally (numbered 1, 2, 3, and 4). The specific sampling positions are shown by the dashed lines. The impact specimens were prepared into standard Charpy U-notch impact specimens (10 mm × 10 mm × 55 mm) according to GB/T 229-2007. Hardness measurements and metallographic analysis specimens were taken from the impact fracture surfaces.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1 Performance Test Results

The hardness and impact energy measurements of the specimens are shown in Table 2. The hardness and impact energy of specimens 1-4 were similar, and those of specimens 5 and 6 were also close. Compared to specimens 5 and 6, specimens 1-4 exhibited slightly lower hardness but much lower impact energy. It can be seen that there are significant differences in impact energy among different parts of the same bucket tooth.

The hardness distributions along the horizontal lines AA’, BB’, CC’, and DD’ , and those along the vertical lines AD, PX, and A’D’ indicates that the hardness was relatively uniform along the middle horizontal lines BB’ and CC’, with no significant difference between the two lines. However, the hardness along the two end lines AA’ (2-3 mm from the tooth tip) and DD’ (2-3 mm from the pit) was lower and uneven. the hardness variations along the vertical lines AD, PX, and A’D’ were basically the same, and all exhibited lower hardness near the tooth tip and the pit, which is consistent with the situation .

3.2 Analysis and Discussion

The fracture morphology and microstructure of impact specimen 2, which had lower hardness and impact energy, and impact specimen 6, which had higher hardness and impact energy, were observed. The fracture morphology and microstructure . Both specimens 2 and 6 exhibited cleavage fractures, but specimen 2 had larger cleavage planes and fewer tearing edges, resulting in lower impact energy. The microstructures of both specimens 2 and 6 were lath martensite, but the lath martensite bundles in specimen 2 were coarser than those in specimen 6. The larger martensite bundles in specimen 2 led to larger cleavage planes during fracture, resulting in lower impact energy. Coarser lath martensite bundles indicate larger austenite grains before the martensitic transformation; therefore, the austenite grains in specimen 2 were significantly coarser than those in specimen 6.

To explore the reason for the coarser austenite grains in specimen 2 compared to specimen 6, the production process of this type of bucket tooth was tracked and observed, and an infrared thermometer was used to measure the temperatures at various stages during the forging and quenching processes. The initial forging temperature was 1180-1200°C, and the temperature after forging and stamping (final forging temperature) was still high, at 1150-1170°C (due to the short forging time and the heat generated during forging, the temperature decreased very little after forging and stamping). After being immersed in water for 10 seconds at the final forging temperature, the tail was exposed above the water surface. At this time, the upper edge of the tail appeared dark red (indicating a lower temperature of approximately 700°C), while the inner and outer surfaces of the pit sidewall remained bright red, with a measured temperature of approximately 900°C. This resulted in the upper edge of the tail (specimens 5 and 6) cooling faster due to the shorter high-temperature austenite grain growth time and finer grains, while the pit sidewall area (specimens 1-4) remained at high temperatures for a longer time, leading to longer austenite growth times and coarser grains. When the bucket tooth was quenched in water, the upper, left, and right edges of the tail were open, making it easy for the vapor film to break and water vapor to escape, resulting in better cooling conditions. In contrast, the pit area of the tail was relatively enclosed, making it difficult for the vapor film to break and water vapor to escape, resulting in poorer cooling conditions. This explains why the temperatures of the upper edge and pit sidewall of the tail differed when the bucket tooth was immersed in water for cooling for 10 seconds and the upper part was exposed above the water surface.

The larger size of the lath martensite bundles in impact specimens 1-4 compared to specimens 5 and 6 resulted in higher hardness in specimens 5 and 6. Additionally, it is possible that the quenching cooling rate of specimens 1-4 was slower, leading to the formation of a small amount of non-martensitic structures (not observed during metallographic examination), further reducing their hardness. the hardness near the pit was lower, and the reason was the same as that for the lower hardness of impact specimens 1-4. The lower hardness at the tooth tip was due to the small amount of material and heat accumulation at the tooth tip, which cooled more significantly despite the high temperature in most areas of the bucket tooth after final forging. Observations during production revealed that the temperature at the tooth tip was lower (750-800°C) when the bucket tooth was quenched in water after forging, possibly leading to a small amount of non-martensitic structure transformation (not observed during microstructure examination), which reduced its hardness.

4. Suggestions for Production Process Improvement

To improve the impact toughness of the pit sidewall area of the bucket tooth, it is necessary to reduce the austenite grain size in this area, which means reducing the time the austenite structure remains at high temperatures after forging. Since the pit area of the bucket tooth is relatively enclosed, and improving the cooling rate in this area is difficult, the only solution is to lower the final forging temperature (which requires lowering the initial forging temperature due to the short forging time). However, lowering the final forging temperature will inevitably result in an even lower temperature at the tooth tip after final forging, causing the hardness at the tooth tip to be even lower after quenching. The solution is to lower the initial forging temperature and then briefly induction heat or flame heat the tooth tip after forging and stamping to increase its temperature. This method is easy to implement and efficient. Additionally, since the initial forging temperature is reduced, energy consumption decreases, and the energy required for reheating the tooth tip may not necessarily increase the total energy consumption.

5. Conclusions

- The hardness and impact energy of different parts of the forged 30CrMnSi steel bucket teeth are inconsistent. The hardness at the tooth tip and near the pit is lower, and the impact energy of the pit sidewall is significantly lower than that of the upper edge of the tail.

- The high final forging temperature and the relatively enclosed pit area result in poor cooling conditions, leading to coarse grains at the pit sidewall and a significant reduction in impact energy in this area.